“You have to establish a relationship with players, gain their trust. If you don’t it’s going to be tough for them to listen to you."

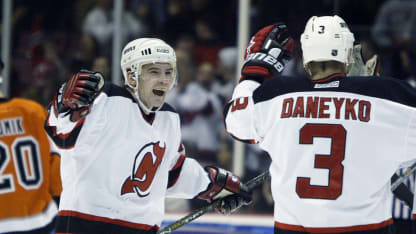

On April 18, 2008, Sergei Brylin skated his final shift as a New Jersey Devil.

It was Game 5 of the opening round of the Stanley Cup playoffs against the hated New York Rangers. Brylin played just 10:04 minutes during the game. But with less than two minutes remaining in regulation, he was on the ice while the Devils were desperately trying to tie the game late in the third period.

After Brylin went to the bench with just over one minute to play, the Rangers scored an empty-net goal. The Devils suffered a 5-3 loss and were eliminated on their home ice at Prudential Center.

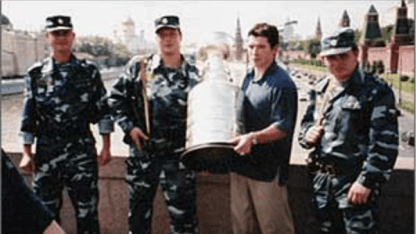

The 34-year-old’s NHL tenure may have ended, but he didn’t hang up his skates just yet. Brylin returned to Russia and played four more seasons in the Kontinental Hockey League, three with SKA (Sports Club of the Army) Saint Petersburg and a final year with Novokuznetsk in 2011-12.

During his four years playing in Russia, Brylin was a frequent visitor to Devils games at the behest of general manager Lou Lamoriello. After his season in the KHL ended in 2012, he joined the Devils during another run to the Stanley Cup Final.

Brylin provided his thoughts and insights to Lamoriello and the Devils coaching staff during that playoff stretch, which ended in a six-game series loss to the Los Angeles Kings. At one juncture during the Final, Lamoriello approached Brylin and said, “‘when you’re done (playing), give me a call. We can talk about you joining the organization if you want.”

Once Brylin officially decided to retire in the summer of 2012, he did just that.

Lamoriello asked Brylin, “what do you want to do?”

Brylin responded, “I don’t know what I want to do.”

So, Brylin did … everything. He joined the American Hockey League team in Albany, doing skills work with players on the ice. He went on a few scouting trips for the team.

“I still remember writing a (scouting) report. I didn’t know what to write or how,” Brylin chuckled.

Eventually, Brylin settled on the coaching route. Lamoriello obliged and added him as an assistant coach with the team’s American Hockey League club. Brylin would fill that role for the next decade in Albany (2012-17), Binghamton (2017-21) and Utica (2021-22). In his lone season with Utica, Brylin helped the squad finished with the best record in the Eastern Conference and win the North Division. The team also set an AHL record by opening the season with 13 consecutive wins.

And just as he had as a player, Brylin fell in love with coaching.

“Helping players to get better. Helping out the team to play at the level we need to play,” he said of what he enjoys most. “I think it’s pretty rewarding when you see things work out on the ice and you get the results.”

Brylin approaches coaching with much of the same mentality that he approached playing.

“It’s just like being a player, you have to get better every day,” he explained. “Hockey is always improving. People are doing different things. You have to look at certain situations for different kinds of views and decide for yourself what is the best way to play.”

And when the coaches’ game plan and the players’ execution comes together, it’s a beautiful thing.

“It’s very rewarding when you see guys execute the game plan and we play the right way and we get the results,” Brylin said. “It makes me very happy.”

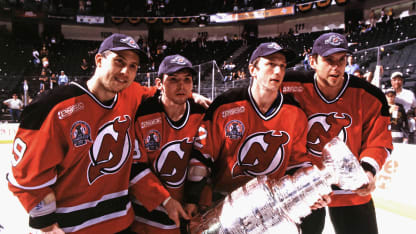

For a player that had overcome so much in his career, coaching was a new challenge for the three-time Cup champ to attack.

“Coaching is not what I was expecting. Especially with the younger generation of players,” he admitted. “The game is different. Players are different nowadays. It’s very challenging for us to find a way to get our message across. You have to be ready, educated and knowledgeable enough to explain every different situation. Why we do things a certain way.

“You have to establish a relationship with players, gain their trust. If you don’t it’s going to be tough for them to listen to you and do what you’re trying to tell them to do. That’s the challenge that I see.”

Brylin has worked with many Devils prospects over the years during his time in the minors, including current Devils forwards Michael McLeod and Nathan Bastian, both of whom played under Brylin in Binghamton from 2017-20.

“(He has) so much experience and knowledge about the game,” McLeod said. “He’s been around the game for a while. He’s won three Cups so he knows what it takes to win. He’s detail-oriented. Personally, coming up throughout Binghamton, he was hard on the details with me, which really helped me as a player.”

“A great guy. For me, he’s done so much. He’s a hard-working guy, big details guy,” Bastian said. “How he used to play is how I try and play. He always gives me that extra confidence boost.”

During his decade of coaching in the AHL, Brylin was honing his skills as a coach. His goal, always, was to eventually work his way into the NHL.

“That was something in the back of my mind all these years,” he said. “I was actually very fortunate to work with three different head coaches. (Rick Kowalski, Mark Dennehy, Kevin Dineen). Learning from them was a great opportunity for me to get better, get ready for the NHL.”

“That’s the beauty of it. He was in the minors for so long that a lot of guys went through him to get to the NHL," Martin Brodeur said. "He’s been working hard with them. I think players relate to another player. Nothing came easy to him. He worked really hard. So, it’s a great example to our young players to have a guy like him be part of their development."

In 2022, Brylin was ready. He was promoted to the Devils coaching staff in New Jersey as an assistant. He was part of a team that won 13-straight games and set franchise records with 52 wins and 112 points.

“It’s just a pleasure to have him around,” McLeod said. “He’s an awesome guy. He loves hockey. Loves being at the rink. He loves his job. He enjoys the teaching aspect of it and trying to make everyone better. He’s a mentor for a lot of us.”

The players respect the fact that Brylin paid his dues for 10 years in the American League before elevating to the NHL.

“It’s cool to see someone that’s won three Cups embrace the job coming back to the minors,” McLeod said, “staring off there and working his way up.”

“He holds a lot of weight. When he speaks up, people listen,” Bastian said. “You look at a guy who played as many years as he did, and even after being in the NHL as long as he was, he still went into the American League and put his time in again but in a different role. He worked his way up."

Bastian added:

“I wouldn’t be surprised if somewhere in the future he keeps moving forward with that, too.”