Legendary hockey reporter Stan Fischler writes a weekly scrapbook for NHL.com. Fischler, known as "The Hockey Maven," shares his humor and insight with readers each Wednesday.

This week zeroes in on a fascinating yet obscure Toronto hero who scored the game-winning goal in one of the longest Stanley Cup Playoff games in NHL history.

Jack McLean wanted to be an engineer. In fact, he was doing very well in his studies at the University of Toronto, but then hockey got in the way. Almost overnight, the collegian found himself wearing a Toronto Maple Leafs jersey en route to one of the most arresting moments in franchise history.

By the end of the 1941-42 season, World War II was in its fourth year and NHL lineups were being decimated by military enlistments. The roster-riddled Stanley Cup champion Maple Leafs tried to alleviate the problem by sending scouts throughout Canada searching for replacements.

One prospect was unearthed by coach Hap Day on a Toronto Junior team called the Young Rangers. A keen talent appraiser, Day believed that McLean, a student-athlete, could help the Maple Leafs. For this to work, a play-and-study deal had to be cut between the University and the defending champions.

"This was a time when crossing the Canada-U.S. border was made more difficult by the ongoing war in Europe," wrote historian Kevin Shea in his book, "The Toronto Maple Leafs."

"The military board refused to grant passports to 19-year-olds to cross the border in order to play hockey. The Leaf brass was aware of this challenge when they signed McLean."

As a result, the gifted center agreed to become a Maple Leaf on the condition that he only could play games in Toronto and Montreal. While his teammates were skating in New York, Chicago, Boston and Detroit, Jack completed his university studies en route to an engineering degree.

McLean finally signed with the Maple Leafs and on Nov. 12, 1942 -- without any practice time -- he played against the Boston Bruins. He was immediately placed on a line with two other young forwards, Gaye Stewart and Bud Poile.

McLean had a three-point game. A day later, The Toronto Star gave him a rave review:

"The 19-year-old broke into the dream world of all kid puck-chasers by firing one goal and assisting on two others as the Leafs spanked the Bruins 3-1. It was McLean, skating as if equipped with rocket blades, who ignited the winning spark."

One reporter wrote that McLean "buzzed like a wet bee." Another labelled him a "toy bulldog who skated miles all night." After McLean knocked a few teeth out of rugged Bruins forward Murph Chamberlain, two dentists reportedly "were screaming McLean's name enthusiastically."

Because of wartime limitations, McLean played 27 out of a 50-game schedule. His nine goals and eight assists helped propel Toronto into third place and a Stanley Cup Playoff berth. Its semifinal opponent would be the first-place Detroit Red Wings who were favored to dethrone the Maple Leafs and win the Stanley Cup.

Not surprisingly, the Red Wings won the opener 4-2 at Detroit Olympia and might have triumphed in Game 2 were it not for the indefatigable goaltending of Toronto's Turk Broda, who made 79 saves that encompassed three regulation periods and four overtimes. Broda's opposite, Johnny Mowers, made 39.

Reporter M.F. Drukenbrod called it, "One of the greatest netminding duels ever waged." Former NHL goalie John Ross Roach, who was in attendance, added, "Both goalies were brilliant. You won't see many games with so many difficult saves."

Heading past midnight, the game remained tied 2-2.

As the clock ticked to 1 a.m., players and on-ice officials were suffering from exhaustion. Some fans left the Olympia but most gutted it out to the finish. Detroit sports columnist Bob Murray -- his tongue well-ensconced in cheek -- observed, "Out of this game will come at least a dozen divorce suits."

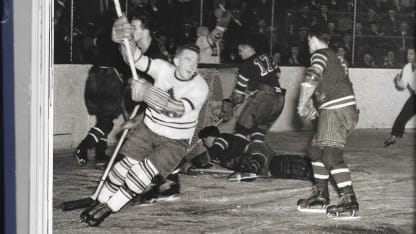

Desperate to break the tie, Day finally dispatched his kid line of Poile, Stewart and McLean (who apparently had received permission to play in Detroit). Day figured that young legs would be his best bet at the 10-minute mark of the fourth overtime.

Sure enough, Poile catapulted them into offensive action. According to one newspaper report, "They swept in three abreast for the assault," whereupon Poile skimmed a pass to McLean. The Toronto Star noted: "McLean whisked it home for the goal that tied the series."

The red light flashed at 1:20 a.m. and the total minutes played, 130:18, made it the third-longest game in NHL history at the time.

"All hands heard signs of relief when McLean smashed the puck home," recorded another newspaper report. "The officials were so weary they could barely get to their dressing rooms."

Unexpectedly, referee King Clancy had a dispute to settle: Who actually scored the decisive goal? Poile was posing for pictures as if he had made the big shot, but Clancy disagreed and credited McLean with the winner.

"McLean admitted that it was his stick that pushed it past Mowers under pressure," noted a reporter covering the game. Meanwhile, Poile shouted, "It doesn't matter who scored as long as we won."

The dispute finally was settled three days later by NHL president Red Dutton after interviews, including one with McLean. Dutton reported that McLean "was greatly disturbed by all the publicity that had developed over his goal."

"McLean told me that he honestly believed he had tipped the puck after Poile's shot," Dutton said. "Clancy insisted that's how he saw the play. And I'm closing the whole incident by declaring McLean the goal-getter."

It was McLean's next-to-last major hurrah since he closed his NHL career skating for the 1945 Stanley Cup-winning Maple Leafs. By that time, former stars were returning from the war and Toronto's general staff decided that McLean no longer was needed.

Resentful of this rejection, McLean turned to the engineering world and became a forgotten hero, except Shea eventually learned that McLean was his great uncle and conducted a long search before discovering his relative in Ottawa.

Poring through items in his uncle's home, Shea found a Stanley Cup ring that Maple Leafs alumni had ordered for surviving members of champion teams, including McLean's 1945 winners. Carrying a blue velvet box with the ring, Shea visited his great uncle, who then was 80.

"I handed the box to the proud champion," Shea said. "Slowly and deliberately, Jack opened the box. He smiled, looked at me and said, 'This just might be the greatest day of my life!'"