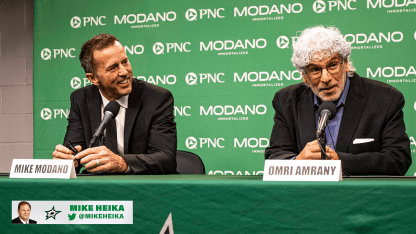

How Mike Modano fell in love with the sport of hockey

From baseball to tennis and even golf, Modano was the definition of an all-around athlete, but the moment he tried out hockey, 'that was it', and he grew to become one of the greatest American-born players to play the game