Everybody knows what Tony Esposito meant as a goalie and teammate. Hall of Famer with the Blackhawks, for whom he authored 15 shutouts as a rookie, still a modern record. Played hurt, played a lot, played with passion.

But what was "Tony O" like as a boss?

"Great," recalled Denis Savard. "Same guy I knew from Chicago. Intense, but also knew how to laugh. And smart. Like his brother Phil. They knew the game. The Tampa Bay Lightning just won a second straight Stanley Cup. But if it wasn't for Tony and Phil, who knows?"

THE VERDICT: Esposito Brothers Know a Thing or Two About NHL Expansion

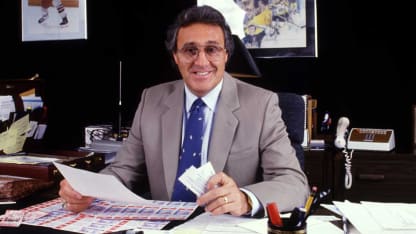

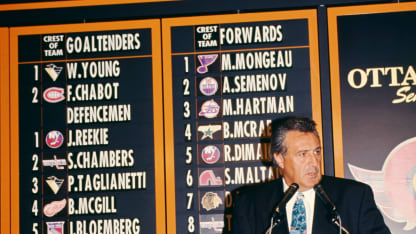

Nearly 30 years ago, former Blackhawks Phil and Tony Esposito were at the helm of building the expansion Tampa Bay Lightning

© B Bennett/Getty Images

© Steve Babineau/Getty Images

© Bruce Bennett/Getty Images

© B Bennett/Getty Images

© Scott Iskowitz/Getty Images