He and his unit would go through the United Kingdom before ultimately ending up in Somerset County, Wales.

“Lovely little town, had a gorgeous cathedral,” Stitt said. “Some things I left out of my book, one of them was that the first warm beer I had had stuff floating in it.

“They told us what our behavior was supposed to be, you know, which went right in one ear and out the other.”

He did eventually land on Omaha Beach after the initial invasion, but not without some difficulty getting to shore.

“The waves were too high to land us, so we just pitched up and down for about two days and they saw how many people they could get seasick on the way over,” he said.

His first night in France, he became aware of the dangers of war as he and his unit had to dig into foxholes as they were bombed by a German plane.

It’s a moment he laughs about now.

“They turned on the spotlights and tried to find him, I have laughed over the years because if they didn't turn those lights on, he wouldn't have known where he was,” Stitt said. “He'd have probably flown right out on the Atlantic Ocean and never been seen after.”

He followed behind the front line of the war for a couple months until his sergeant decided he was ready to operate a Sherman tank, where he would spend the rest of the war.

“We all went with the same thing in mind,” Stitt said. “If this tank is made in America by Americans, there isn't anything in the world any better than this tank.”

He was initially trained to be the gunner in a tank; however, he was needed as a loader. He was more than happy to make the adjustment if it meant being inside of a well-armored vehicle.

“I felt better because I'd already been shot at by a sniper, and I had already been around with bombs dropped,” Stitt said. “I thought, well, once I'm in this iron shell, it's going to be different, you know. I'm protected.”

It was also easier on his conscience to be the loader rather than gunner.

“When you're putting all those shells in there, you don't think that they're shooting people. You just do what you're supposed to do,” he said. “Then when you move over near the gunner, you got the crosshairs and all of a sudden you're going to step on that trigger. It's just not the way we're brought up.”

Although he felt safe inside the tanks, there were many instances he came inches away from death.

During a battle where he lost his tank commander and had to be the senior officer from that point forward in the day, he lost his tank and he and his unit had to rush to a nearby house to take cover.

“I reached up and my head felt cold, and I just brought down blood," Stitt said.

He was wounded by shrapnel that fortunately did not cut deep enough, and he was able to survive. However, he was picking shrapnel out of his head for years following the war. When he was in the field hospital, the doctor started picking out pieces, one of which Walter has saved for 80 years since and still has hanging in his war memorabilia room at home.

He was able to keep calm during this by operating emotionlessly and without too much thought.

“I'm obeying orders. He tells me what the target is, and I'm heading to that target,” Stitt said. “Of course, I've got my head down there most of the time watching to see if I see a target.”

Since he was in a tank while he was in France, he could not recall the specific towns that he fought in. However, he remembers he fought through three towns in France.

When he and his unit arrived in Belgium, he remembers surrounding German forces in Mons, part of a decisive victory for the Americans over Germany.

“A few Germans tried the next day, when they realized they were surrounded, to make it out and didn't make it, and the rest of them surrendered. It was something like 14 or 15,000 Germans that we captured in Mons,” Stitt said.

Stitt also fought in the Battle of the Bulge and was in one of the first tanks to cross the Siegfried Line into Germany.

After seeing three Sherman tanks get destroyed, being wounded twice and watching many of his fellow countrymen lose their lives, Stitt left Europe safely and returned home to his parents.

Post-War Life

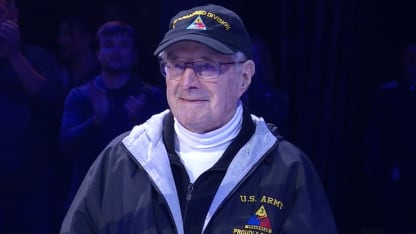

For his efforts, Stitt received a Purple Heart with the Oak Leaf Cluster, and a few years ago he was awarded the Legion of Honor, France’s highest honor for military members and civilians.