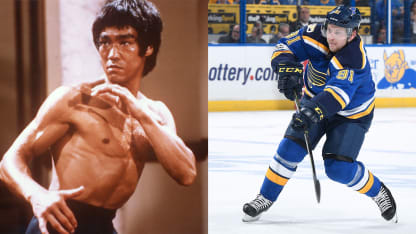

In August 1964, at the Long Beach International Karate Championships, the same event that would launch the storied-and at times mythical-careers of such martial artists as Chuck Norris and Joe Lewis, a 23-year-old upstart named Bruce Lee stood less than an arm's length away from Bob Baker, a colleague who had volunteered for the demonstration. He positioned his hand, fingers extended, less than an inch from Baker's chest. His feet were shoulder-width apart, with his right foot forward and his knees slightly bent. Then, in one swift, seamless motion-and without ever pulling his right arm back for leverage - he thrust his fist into Baker's chest. Baker flew backwards and into the chair behind him. Lee had generated power - enough power to take down a man - seemingly from nowhere. He didn't appear to be in a position to throw a punch with such force, nor did he telegraph the attack with unnecessary movement. Lee struck a crippling blow that no one saw coming. And by the time they did see it, Baker was already on the ground.

With this "one-inch punch," Bruce Lee introduced himself to the martial arts elite.

Wrists of Fury: Tarasenko, Lee and the NHL's one-inch punch

\\\\

On a steamy Saturday in St. Louis, Vladimir Tarasenko sat down on a couch in the living room of his home. His son Alexander, a few days away from his first birthday, was sleeping upstairs. So was his 10-year-old son Mark, who was napping before his own hockey game later that day. The house was quiet. Yana, his wife, noiselessly slipped from the kitchen and into the living room and placed a cup of tea on the table in front of him. Dressed in a billowy blue-and-white linen shirt dress, her long hair gathered in a loose bun, she carried herself with easy elegance. Tarasenko looked up and smiled in appreciation, sensitive to the newness of the offseason routine. The team had recently been eliminated by the Nashville Predators in the Western Conference semifinals. The loss was a sharp disappointment and a cut Tarasenko still felt. But now, in the absence of morning practices, evening games, constant flights and taxing road trips, the family found themselves with an abundance of what had been scarce for the past nine months: time.

"It's kind of hard for first maybe a week to get used to stay every time home. It's kind of weird, you know?" He smiled. "Yana said it's kind of like every day Sunday now, because you're every day home."

The 2016-17 NHL season, Tarasenko's fifth in the league, was chockfull of happy moments, despite months of inconsistency - which ultimately resulted in the firing of head coach Ken Hitchcock - and the team's second round loss. Tarasenko found himself in a leadership role that had expanded exponentially over the summer. The departure of veterans David Backes, Troy Brouwer, Steve Ott, and Brian Elliott - a critical contingent to the Blues success the previous year - was a summons to step up and, by default, into a brighter spotlight.

And step up he did. Tarasenko netted 39 goals, two of which came against the rival Chicago Blackhawks in a 4-1 victory at the 2017 Bridgestone NHL Winter Classic, thrilling the 46,000 people who swathed Busch Stadium in blue.

It was no wonder he furnished such an inspired performance. Two days before, after the Winter Classic Alumni Game, the current Blues squad made their way into the Cardinals clubhouse to hobnob with a lavish gathering of NHL legends. While the past and present exchanged pictures and autographs, Tarasenko stole away to a quiet reception area of the Cardinals clubhouse. There, just outside the buzzing locker room, he and his son Mark posed for a picture with Bobby Hull. It was an intimate moment as the two spoke - Tarasenko nodding his head deferentially, though it was obvious the respect was mutual. Then, abruptly, Hull placed his hands on the Russian's shoulders and leaned forward.

"Keep shootin' the puck, kid," he instructed in his throaty growl. "Keep shooting the puck."

This, Tarasenko does.

Over the past three seasons, only Alex Ovechkin has scored more goals than Tarasenko-a stat that has been bandied about though perhaps underappreciated. But it's not just the number of goals he's scored. It's how he scores them.

"He can legit score from 40 feet," said Mike Liut, the former Blues goaltender who served as the team's liaison when Tarasenko was playing in the KHL, "and that's not with a screen. It's straightforward."

"The release of his shot is second to none," stated Hall of Fame defenseman Al MacInnis. "I think the biggest thing is it's unpredictable, the way he's able to disguise when he's going to shoot."

MacInnis was standing outside the Blues locker room at Scottrade Center after a morning skate late in the season. As he spoke, a glitzy assortment of former Blues percolated down the hall - Martin Brodeur, Keith Tkachuk, Bobby Plager, Kelly Chase, Bernie Federko. The abundance of celebrity, not just at Scottrade Center but at local rinks across town, is common in St. Louis, where a vibrant alumni community rivals that of any NHL city.

"I've played the game and watched the game a long time, and whether it's the Brett Hulls or the Mark Messiers and the guys that really had a great release on their shot -" he shook his head - "I'm not so sure that Vladi's isn't the best I've ever seen."

\\\\

On November 12, in the third period of a wacky game that would see the Blues fall to the Columbus Blue Jackets by the score of 8-4, Tarasenko took a blue line pass from defenseman Kevin Shattenkirk. With the puck on his stick, he glided to the top of the faceoff circle where he made a single stutter step, a cutback move, to dispense of Columbus defenseman David Savard. Before Tarasenko even reached the faceoff dot, the puck was in the back of the net. There was no windup, no shoulder drop. The puck had been parallel with his skates when he shot it - which, if not exactly a lame-duck location, is at least a suboptimal one. Still, somehow, Tarasenko had generated power - enough power to beat one of the League's best goaltenders - seemingly from nowhere. Tarasenko fired a shot that Sergei Bobrovsky never saw coming. And by the time he did see it, the puck was already in the net.

The goal was quintessential Tarasenko. Shunning the flash and dash of contemporary superstars, Tarasenko is astonishingly minimalistic. Absent from his highlight reel is the profusion of dekes and dangles, the goal-of-the-year candidates preceded by the escalating shrieks of play-by-play men. (Yes, Tarasenko's goals even sound different). Instead, Tarasenko floats with impossible economy of motion and fires rockets without warning, catching everyone, from goalies to broadcasters, off guard.

But what makes Tarasenko's shot, a deceptively straightforward affair, so difficult to stop?

Before Bruce Lee threw the punch that would rocket Baker backwards and his own career to fame, he lectured on the inefficiency of traditional martial arts techniques. The old ways, he said, with their embellished movements and elaborate delivery, were too slow. Instead, he preached a philosophy of speed, agility, practicality and explosive power.

Fast forward half a century, and swap speed for a quick release, agility for a mastery of edges, practicality for playing goalie gaps, and explosive power for velocity, and Bruce Lee's infamous one-inch punch translates like tracing paper over a diagram of Vladimir Tarasenko's wristshot.

Bucking the traditional identities of razzle-dazzle goal-scoring - think Ovechkin's million-dollar windup, Sidney Crosby's backhand or Evgeni Malkin's spin-o-ramas - Tarasenko omits splash. He doesn't pull the puck in for a snapshot, pull it back for a wristshot, or wind up for a slapshot. He can shoot when the puck is in tight. He can shoot if it is away from his body. He can shoot off balance. He doesn't massage the puck at all. He doesn't put his head down. Instead, his head is up, almost as though he were stickhandling.

"There's such a disguise of when he's going to shoot. He doesn't drop his shoulder. He doesn't move his body in a certain position so you know he's going to shoot," MacInnis said. "It's just… bang! It's off his stick."

"He sees goalies in a different way than most guys do," said Blues goaltender Carter Hutton. "He does a lot of things to get open and battle for space - and he's such a strong guy that he can do that - but a lot of times he uses the movement of the goalie to his advantage."

Hockey is a game of gaps, Hutton explained. At all times, each body on the ice has momentum. The key is to control the gaps and capitalize on your opponent's motion.

"He catches guys moving. He shoots to places that are going to open up. He just understands. And his release is so - it's a sneaky release. If I turn the wrong way - as soon as you start to move a bit - he releases it. And at that point you don't have your total body control." He shrugged. "Other guys use their stick and use the full leverage. [Vladi's] is just a quick sling of the wrist and it's gone."

Like a one-inch punch?

Hutton considered a moment and then nodded. "Yeah, that's a good comparison."

\\\\

Tarasenko smiled when I asked him if he were familiar with Bruce Lee.

"You mean the guy that does this?"

He was sitting on the couch, and he leaned forward as he spoke, positioning his left hand, fingers extended, less than an inch from his right hand, which was also extended. Then, in one swift, seamless motion - and without ever pulling his arm back for leverage - he thrust his fist into his palm.

"Yeah," he said with a wry smile. "I know him."

To provide context for the question, I told him Hutton and I had discussed the comparison.

He broke into an amused grin. "He told me that."

As the ready precision with which he mimicked the punch suggested, Tarasenko is a longtime fan of Lee. On road trips, when he finds himself with free time, he'll search for Bruce Lee videos, specifically the one-inch punch, and study his movements. When I told him his own punch was surprisingly practiced, he laughed.

"I 'practice' with my oldest son," he said. "He likes it. He likes to fall back on the couch to make it more fun."

But beyond the exhibition of the one-inch punch, Tarasenko said he admires what Bruce Lee represents: "how much success people can get if they work hard and they believe in themselves."

For his part, Lee believed the traditional martial arts were too unwieldy. "It's not the daily increase," he said, "but daily decrease. Hack away at the unessential." He developed a system of fighting without fixed positions, attracting celebrity students such as James Coburn, Steve McQueen and Kareem Abdul-Jabar. His philosophy also shed light on what makes Tarasenko's shot so successful, though Tarasenko didn't always shoot the way he does now, nor did his shot evolve organically. His dad, Andrei, taught him.

Andrei Tarasenko played for Yaroslavl in the Russian Superleague (the KHL wasn't around yet) in the 1990s. He led the League in scoring in 1996-97. He also played for Russia in the 1994 Olympic Games in Lillehammer. During those years, Tarasenko lived with his grandparents in Novosibirsk in Siberia. His grandfather, a hockey player himself, taught Tarasenko to skate and signed him up for his first hockey teams. He went with him to every game and on every road trip throughout his junior career. During this time, Tarasenko practiced his shot, but not more than he worked on any other part of his game.

"When I used to play in Russia a long time ago, when I grow up, you don't have much ice," he said of his practice habits when he was young. "The only chance to skate was outside, you know?"

He gave the example of summer camp, where he spent three weeks each year when he was a kid. He and his friends would hang up giant fishing nets and place plastic bottles where they guessed the four corners of a hockey net would be. Then they'd fire pucks at the bottles.

"It was like a shooting range for us," he said, shrugging. "It was like the shooting room in Scottrade for me now. But it wasn't like I stay there over the night - " he shook his head to emphasize the negative - "and no. Just normal. Because when you're younger, and you have enough to score a lot of goals, you score every game and get points every game. You don't think, 'Oh, I need to shoot 200 more pucks."

By enough, Tarasenko meant skill. Tarasenko was extremely successful as a youngster - he once scored a point in every game for over five years - but Andrei knew that what worked against Tarasenko's peers would not work against grown men. The game would only get faster, the defenseman keener, the goalies steelier. Tarasenko was in his mid-teens when Andrei told him it was time to change his shot. Andrei, like Lee, hacked away at the unessential.

"He told me to shoot like I shoot now for the first time, and it's uncomfortable. I'm like, 'I can't do this, because I usually like to shoot like - " he stood up and demonstrated, swinging his arms back. "All guys in junior like to pull it back nice and swing it hard to score top glove or top blocker. Everyone wants to do this when they're young, you know?"

He explained that young skaters prefer a splashy windup not simply because of vanity - though that plays a part - but because kids simply don't have the strength to fire a heavy shot without the leverage of a flexing hockey stick.

"So this nice swing -" he demonstrated again - "and the puck goes up, and you feel like you're a good hockey player when you're young." He laughed. "But it wasn't like I got it in one day. It was really uncomfortable to shoot like this, to not stickhandle before you shoot."

For Tarasenko, at least in junior level hockey, time to shoot was never an issue. Plus, he was already scoring goals and tallying points. He didn't see the need to change his shot.

Andrei was insistent. He told his son that if he had a three-second window to shoot the puck, he needed to shoot it in the first second.

"I would ask why I need to shoot here if I have two more seconds," Tarasenko continued.

Andrei's answer was twofold: Tarasenko would have more time to make decisions and, if he could get his shot off two seconds before anyone was expecting it, no one would be able to catch him.

"And then I start practicing and practicing - " he shook his head, exhaling. "It was hard because you never do this before. But then you just get used to it - and keep doing it now."

The key to Andrei's shooting style wasn't just quickness. It was also power. Lots of guys fired heavy shots. Lots of guys fired quick shots. But who could fire a shot that was just as heavy as it was quick? For Andrei, it was simple math: add velocity to the shot and subtract time for execution. And the former required muscle.

Tarasenko is astonishingly - almost unbelievably - strong. More than that, his strength seems to surge on his skates. For all of the laurels heaped upon his shot, Tarasenko is arguably one of the best skaters in the NHL.

"It's not speed," explained Liut. "People equate skating with how fast you are. That's an element of it, but it's the strength on his skates. He can make you turn as a defenseman. If you're protecting too much against that, and he goes wide and gets his shoulders past you, you're not going to stop him. It's a different element of skating. It's power."

"When you watch him skate, you'd think he weighs 150 pounds," said Paul Stastny, whose locker is adjacent to Tarasenko's in the Blues locker room. "His edges… he's basically floating on the ice. It's very impressive. If he just had the quickness he did, I think he'd still score goals. But the fact that he shoots it that hard makes it that much harder to stop.

"I don't think people realize how hard that is to fake a shot and change your angle and transfer the power all in one motion. He does that with ease."

\\\\

Tarasenko is famously humble. ("Showing off is the fool's idea of glory," Lee once said). He deflects praise and, when it can't be deflected, is visibly uncomfortable until the conversation moves forward. When I mentioned Al MacInnis' accolades - that Tarasenko's shot is perhaps the best he's ever seen - he was, for a moment, disbelieving and then quieted by the weight of the honor. He looked down at his hands. Then he smiled, embarrassed, "That is a good [compliment]."

Tarasenko's modesty stems from deep gratitude and razor-edged competitiveness. Regarding the former, he is acutely aware of the sacrifices his grandfather and father made for him and the wisdom they imparted. Also, their patience. He was, admittedly, not a willing student.

"I wasn't easy to coach," he said with a culpable laugh. "Sometimes I get angry. It was pretty tough - tough kid to explain something."

Specifically, Tarasenko's grandfather and father had to teach him how to handle losing.

"I'm a heavy guy with it. Like, I'm really nervous about losing. I hate losing. Even a regular season game or something like that. There is night sometimes it's hard to fall asleep." He shook his head. "Not sometimes. A lot of times."

Tarasenko said that when he was a kid, he was devastated by defeat. He would cry when his team lost. When his team was trailing, he was tempted to quit.

"But my grandfather teach me how to - what to do to win. You need to do something to win, you know? Wins don't come themselves. It's not gonna bounce out from nowhere.

"Obviously, this year, things didn't go our way. So what are you gonna do now? Over the summer get better and stronger and come back and fight again? Or are you gonna just let it go and lose?"

As if on cue, Alexander teetered into the living room, followed by Yana. Tarasenko's face burst into a smile, radiant with delight. Alexander's explosion of white hair suggested he had napped successfully, as did his dimpled grin. I asked if Alexander is always this happy.

"Of course," Tarasenko said, giggling and lifting his younger son, "because daddy is home." Then he added, "He will be a hockey player, probably."

After a few more moments of giggling - both father and son, whose likeness extends even to their laughs - Tarasenko resumed the conversation.

"With Mark right now, I can see myself in his spot when I was 10 years old. And you have an OK game, but you don't like a game, and you feel a ton of the world. You're frustrated.

"There was periods of my life when it wasn't going my way, and there was two ways: they make you stronger or they get you and make you [worse]. There is no staying the same level after you go down, you know?

"So that's what I try to explain to him right now. To fight for it. To don't be upset. Don't show anyone you are upset because people see you upset or frustrated, and they will take care of you. And you don't have a chance to win at all."

Alexander, who had been toddling around the couches and banging the palms of his hands on the glass coffee table throughout the duration of his father's speech, picked up a small, blue ball and tossed it at Tarasenko's feet.

"Gooooal!" Tarasenko cried, raising his hands in celebration.

Alexander - who hadn't stopped smiling since he woke up from his nap - smiled wider and raised his arms, too. This pattern repeated itself several times until the whole family was involved: Alexander throwing the ball, and his dad, mom, and brother Mark - who had by now come downstairs - cheering, "Gooooal!"

At one point, a particularly boisterous throw sent the ball flying into the hallway. In his hurry to retrieve it, Alexander tangled his stout legs and tumbled.

"Oh!"

Tarasenko held out his hand to gently shush Alexander's audience. Then, unwittingly illustrating the last point he had made, he turned around and began walking nonchalantly around the room as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened.

Alexander, on the verge of tears, looked at his father, who by now was looking in any direction but his.

Then, after a moment's reflection, he steadied his lip, smiled, and got back up to play.

\\\\

In 2011, at the World Junior Championship in Buffalo, New York, Team Russia seemed destined for a silver medal. They were trailing the Canadians 3-0 heading into the third period of the championship game. But a herculean effort by a line of Tarasenko, Evgeny Kuznetsov and Artemi Panarin spearheaded a charge that would eventually see the Russians score five unanswered goals. The three tallied seven points between them, with Tarasenko logging both a goal and an assist.

"Vladi's line brought them back," Liut said. "That line won that game. Vladi was determined. He was the driver on that line."

The game marked the first time Liut saw Tarasenko play in person. I asked him if Tarasenko's wristshot had first lured the Blues to court the Russian. It wasn't. While Tarasenko's shot was heavy enough to turn heads, it was his all-around play - not just shooting skills, but skating and passing, size, and such intangibles as vision, intensity, toughness, and commitment - that convinced the team he would be a success in the NHL. He was a teenager who could drive past men. He was quick to his spot - quicker than he needed to be on the larger, European ice surface. He was strong down low in the offensive zone. He could escape coverage. And he was willing to go into the hard areas time and time again.

"What Vladi could do is overpower people," Liut said. "He was the real deal. His passing is extraordinary. It's like his shot. It's a bullet. It's as good as it gets. He's a great hockey player. He's an elite player. It's more than just shooting the puck." He paused and laughed. "But that definitely helps."

Liut noted that Tarasenko entered the NHL during what he called the "decline of the Russians." At the beginning of the 2000-01 season, there were over 70 Russian players in the NHL. By the time Tarasenko entered the league in the lockout-shortened season of 2012-12, there were fewer than 30, the lowest number in over two decades.

"There was a host of '82-born players that came over and just couldn't make it. Highly-touted players with exceptional skill that just didn't make it," Liut continued. "There were a lot of them. That was the concern at the time.

"But he told me in English when I met him the first time that he wanted to have success in the World Cup and the Olympics, but he really wanted to play in the NHL. He felt he could compete at that level. And he did. He did exactly what he said he was gonna do."

\\\\

It has become a familiar sight at Scottrade: Yana, standing at ice level by the Olympia doors, holding Alexander on the ledge where the boards meet the plexiglass. Mark is by her side in a Tarasenko jersey. Alexander's palms bang against the glass, like they do against the coffee table at home. He bounces and smiles as he waits for his dad to skate over. Here the trio wave and cheer for the duration of warm-ups. Home games are a family affair.

"Yep. Every single game," Yana said. "I think Mark loves it."

So does Alexander, though it took him a few games to appreciate the limitations of an NHL arena.

"First time, when she bring him in, he was not even understanding what's going on," Tarasenko said. "I tried to like, 'Hey, it's me! It's me!'" he said, waving as he explained. "I even took off my helmet."

After a few more games, Alexander recognized his dad and smiled. But the improvement was short-lived.

"He decided, 'I can't get in!' So he started crying then," Tarasenko laughed.

For Tarasenko, his wife and sons temper the volatility of the NHL season and keep him grounded in his convictions, both on and off the ice.

"I want my kids to be good humans first," he said, stressing that skill means nothing if you are a "great hockey player, but you have a bad personality."

"I tell them you need to be humble with people. You can't judge people only when you see them, because maybe there's a story behind it." He also warns them about jealousy. This last item is especially important.

"There are two ways of being jealous, you know? In Russia, they call it white and black. If you say black, it's a bad one. That's when you really, really jealous. And if you say white, it's like you want to be in his spot, but you're happy for him. But it makes you work harder to get there."

He paused for a moment.

"And if there is another one, it is believe in your family, because I think family is a really, really strong power. It's hard to understand when you're 10 years old right now that it's actually like this, but it's what we try to do. We tell him family are the ones who always can help you, whatever happens. We're not gonna turn away, or turn our back for you."

\\\\

In his treatise on martial arts, Tao of Jeet Kune Do, Bruce Lee wrote, "There is no mystery about my style. My movements are simple, direct and non-classical. The extraordinary part of it lies in its simplicity."

The same can be said for the brilliance of Tarasenko's wristshot, though one could argue the simplicity itself is the mystery.

"To be honest, I don't know how he shoots like that. I've never seen somebody who can get a shot off so quick and so accurate," said teammate Ryan Reaves.

In the locker room, Tarasenko is flanked by a concrete wall on one side and Reaves on the other, which is to say, he is flanked by concrete walls. Reaves is the only player on the team who rivals Tarasenko in raw strength.

"The thing that blows my mind with his shot is he can shoot through a guy's stick and still get it in the right spot," he continued. "A lot of times, you see those shots get deflected. I don't know how he does it."

David Perron, whose flash-and-dash style earned him the NHL's Goal of the Year in 2009 for a two-zone masterpiece against the New York Islanders, said he asks Tarasenko about his shot-details about his mechanics or how he reads defensemen or how he decides where to shoot - and, in the offseason, works on applying those principles to his own game.

Back at Tarsenko's home, in the Zen-like quiet before his sons woke up from their naps, I asked my own questions. What does he do differently than other players? Why does the puck explode off his stick, ostensibly shirking the laws of physics?

He considered the question.

"It's not close to the body," he said. "It's more like -" Here he broke off and started again. "Don't let the goalie a chance to read your shot - " Another pause. Finally, after a self-conscious attempt to put into words what he does with unselfconscious ease: "I don't want to explain it a lot because then they're gonna know how I shoot it."

In one of the rarer moments of our conversation, he didn't smile.

Tarasenko's grandfather has said he prefers to call his grandson a master rather than a superstar. And while Tarasenko, characteristically downplays the epithet ("It doesn't matter what they call you," he said), the distinction is in the nuance. A superstar is a performer, a patron of spectacle. A master, on the other hand, is a philosopher, a student of what's left when all the spectacle has been stripped away. Tarasenko, in that sense, is the latter.

And every master has his secrets.