VANCOUVER, BC - "I'd like to speak to the general manager regarding a tryout."

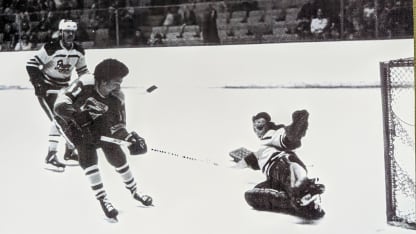

Ralph Taylor was looking for a place to play. He didn't have an agent. There was no internet. And although he'd played Division II hockey at the collegiate level in the U.S., as well as on a semi-professional team in his native California, he didn't necessarily have an NHL-calibre resume.

Black History Month: How hockey helped Ralph Taylor find his purpose

By

Farhan Devji @farhandevji / Vancouver Canucks

But like any young player, Taylor dreamed of playing in the NHL. And perhaps more importantly, he believed that he could. Taylor also had some connections to the Vancouver region, having previously attended a hockey school in Nelson, B.C. So, as one would in 1974, he picked up the phone and decided to call the Vancouver Canucks head office.

"Come on down," they told him.

Taylor remembers sitting in an office with then-Canucks assistant general manager Greg Douglas, sharing some of his experiences and pleading his case, before Douglas simply asked: "Do you think you could play pro hockey?" Less than 24 hours later, after checking in with some of his previous coaches, they invited him to their upcoming rookie camp in Victoria.

Just like that.

"That was all they needed to know," Taylor said, marveling at their "open-door-policy" for a Black player during a time when there were very few people of colour in the NHL. "Hockey opened doors for me and my brothers, and we just went right through them."

Taylor grew up in Berkeley, California, about four blocks away from an ice rink. But ice skating or ice hockey wasn't exactly on the radar for most California kids back then. Instead, he went roller skating every Saturday morning at Rollerland, and played sports like basketball, baseball, and football. Eventually, though, he ventured into the ice rink with a friend and saw a couple kids and their dads knocking this "little black thing around the ice."

"What the heck, we'll try that," they thought to themselves.

And so began his journey in hockey.

Taylor didn't come from a lot. At an early age, he and his brothers had to make their own sticks for street hockey, nailing together pieces of wood they grabbed from the bins at a nearby lumber supply company. For ice hockey, he remembers having to wear football pads and baseball socks and getting the rest of his equipment from The Salvation Army.

Aside from his two brothers, he never played with or against any other Black players. Sometimes, through minor hockey ticket promotions, Taylor had the opportunity to watch the San Francisco Seals play in the old Western Hockey League.

And it was the same thing.

"You just noticed it was almost exclusively white players," Taylor said. "You couldn't help but notice it. In a strange way, despite that, the game became very familiar for us. We embraced the game, and the game embraced us."

It wasn't until an 11-year-old Taylor spotted Willie O'Ree, then a member of the Los Angeles Blades, play a game against the Seals that he realized there were other Black hockey players.

"That was quite meaningful," Taylor recalled. "Just because I don't see any, it doesn't mean they don't exist. They must be out there. There must be others."

So Taylor started taking the game more seriously.

In Grade 9, his high school basketball coach told the players on the team that they could no longer play a club sport and school sport at the same time. They had to choose one.

"I took about 30 seconds and walked right off the court," Taylor said. "Hockey was my game. He was flabbergasted. How could a young Black kid, in the '60s, who's a good basketball player and getting good grades, not continue? He just couldn't believe it."

Taylor ended up playing in the state championship at the U13, U15, and U18 levels. This opened more doors, including an opportunity to attend the hockey school in Nelson, a spot on the semi-pro team in Fresno, and a scholarship to play hockey at Bowdoin College in Maine.

Meanwhile, his brothers Greg and Henry were also advancing in the sport - notably, Henry played junior hockey for the Edmonton Oil Kings and professionally for the Johnstown Jets, where he scored 50 goals one season and was a linemate of Bruce Boudreau.

It was around that time Taylor phoned up the Canucks and decided to give pro hockey a shot himself. Ultimately, he was released following the rookie camp - the Canucks had just drafted a few left wingers, his natural position, so he decided to play centre and didn't fare as well. And that signalled the end of his hockey career. But he credits hockey, and perhaps a little destiny, for bringing him to the city of Vancouver, where he quickly realized he was meant to be.

In 1978, Taylor came across a book that had just been released by North Vancouver-based author and educator Crawford Kilian, called Go Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia. Through the book, Taylor learned that the province's first Black immigrants came from the San Francisco area.

"They were very instrumental in organizing the province, before it was even a province," Taylor said of his learnings. "Some of them were merchants and businesspeople, along with being miners, and so on. A significant number of them came up to exercise their full rights as citizens here, which they couldn't do in the United States."

As someone who followed a similar path, making Vancouver home after growing up in the San Francisco area, that struck a chord with Taylor. He took it as a sign and decided to get involved with different Black cultural organizations around Vancouver.

"I felt like I could contribute something," he said. "There was this natural affinity."

Taylor was passionate about performing and writing, so he got involved with the Free Black Creative Arts Theatre for Children to help bring cultural arts to young kids in the area. Unlike where he grew up in Northern California, there wasn't a large Black community in Vancouver, so Taylor said the goal was to help them get a better sense of their Black culture. Later on, he became president of the the Black Historical and Cultural Society of British Columbia, helping stage the opening celebration for Black History Month every February.

One year, while perusing a community newspaper, he came across a photo of a 17-year-old Black man dancing. Taylor reached out and asked if he wanted to perform in the opening celebration, which he ended up doing. Six months later, the young man spotted Taylor on the street, ran up to him, and thanked him. As a result of that performance, he'd secured a contract with a professional dance company.

Taylor, now 70, tears up as he recounts the story.

"You kind of realize, when you pursue something that is part of you are, what you believe in, and it impacts others such that they can pursue their own dream and passion … that was the most meaningful aspect of anything I did in the community," he said.

In sports, you often hear the stories about those who made it. Those who overcame the odds to make it to the top. But for every one of those stories, there are thousands more like Taylor's. While hockey was his first passion, it helped him find another one.

It helped him find his purpose.

"You look back at your life and you say, 'Why am I here?' Both why am I here on this earth, and why am I here in this physical place?" Taylor said. "And I realized why I was here on this earth at a very young age. It donned upon me. My life purpose is to utilize insight, passion, and creativity to foster and develop greater understanding between people and cultures. And I realize that I did that in a way as a hockey player."

"Despite the fact that I didn't become a professional hockey player, I didn't allow any barriers - whether it be racial, financial, or whatever - hold me back in pursuit of that dream," he continued. "As it turns out, I didn't make it. But I can look back and feel very, very fulfilled that I gave it everything I had at the time. Then you move on, and you find those other passions in life to pursue. And they're there for you."

The Vancouver Canucks are honoured to join in the celebration of Black History Month this February. Follow @canucks on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram for stories, content and more.