It was a typical Career Day for the Grade 6 class at Buchanan Public School in Scarborough, Ontario, complete with the usual allotment of fire fighters, policemen, nurses and other accomplished professionals on hand to chat with students.

Mike Marson, who played for the Washington Capitals during their 1974-75 expansion season, still remembers sitting in the classroom that day in 1967 along with his childhood friend and future New York Rangers forward Wayne Dillon.

"They were trying to get us to think about more than being in Grade 6," Marson recalled.

"So, Wayne was asked what he would someday like to do for a living, and he said he wanted to be a National Hockey League player. 'That's great, good for you,' he was told. Then I was asked the same question and I gave the same answer. The [staff] just looked at each other and shook their heads as if to say, 'Kid, you have no idea the mountain that you think you're going to climb.'"

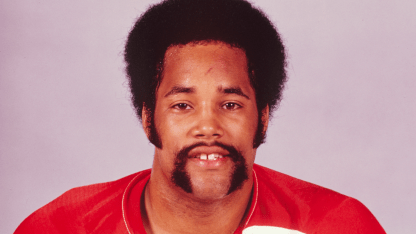

The doubters were always going to be there because of Marson's skin color. He was a black kid looking to make it big in a historically white sport.

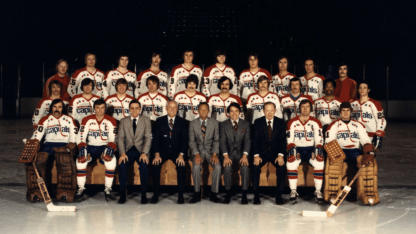

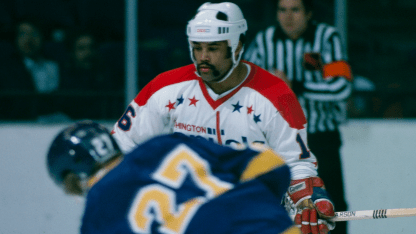

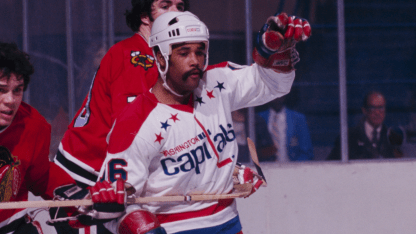

Against the Odds: Remembering Mike Marson's Career with the Caps

Sixteen years after Willie O'Ree broke the NHL's color barrier, an 18-year-old Mike Marson made his NHL debut with the expansion Capitals

Black Hockey History | Mike Marson