For the better part of five decades now, the Washington Capitals have been delighting and disappointing hockey fans in the DMV, bringing varying degrees of exhilaration and excitement mixed with heartache to an ever growing and expanding group of fans. From their maiden NHL voyage in 1974-75 when they set an NHL record for single-season futility that may never be matched, to the team's current run of 14 playoff appearances in the last 15 seasons and a Stanley Cup championship in 2018, the Caps have supplied a wild rollercoaster ride of emotions on the ice for nearly 50 years.

Red Letter Day

Caps celebrate half century of NHL hockey in the District

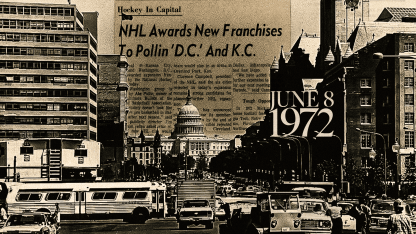

Although the team's official 50th anniversary is still a couple years ahead on the horizon, today is the day we celebrate the actual 50th birthday of NHL hockey in the District. It was 50 years ago today - on June 8, 1972 - that Washington's NHL hockey life began in a hotel in Montreal when the city was granted its NHL franchise following weeks of intense lobbying from Abe Pollin, who was the owner of the NBA's Baltimore Bullets (now the Washington Wizards) in those days.

Although the odds seemed significantly stacked against Pollin in that drastically different pro sports climate of the late spring of '72, the Caps' original owner was able to persevere and to persuade, with an emphasis on the latter. Looking back at it now, it's quite remarkable that Pollin was able to pull off Washington's admission to the NHL fifty years ago today.

Pull up a chair, and we'll tell you how it all went down.

Along with partners Earl Foreman and Arnold Heft, Pollin purchased the Bullets (née Chicago Packers) on Oct. 24, 1964. The Bullets had just started their fourth NBA season and their second in Baltimore, where they played their home games at Baltimore Civic Center, which opened in October of 1962. The Civic Center had a seating capacity of 12,289 for basketball.

In missing the playoffs for a seventh straight season at the outset of their NBA existence, the Bullets drew an average of just 4,754 fans for 36 home dates in Charm City in 1967-68. That figure ballooned to 7,635 - just over 62 percent of capacity - for 38 home dates in '68-69, but that was the attendance peak of the Baltimore years. Patronage then slipped back to roughly half of the arena's capacity even as the team was averaging 48 wins a season over its next five campaigns in Baltimore.

In July of 1968, Pollin bought out his partners and took ownership of the Bullets outright. After the team drafted dynamic guard Earl "The Pearl" Monroe with the second overall pick in the 1967 NBA Draft and landed star center Wes Unseld in the same slot in the 1968 Draft, a run of a dozen straight playoff appearances followed from '68-69 through 1979-80, leading to the team's only NBA championship in 1978.

Born in Philadelphia, Pollin moved to the District as a young boy and was raised and schooled in the city. He had a great deal of pride in the city and the family business was construction, so he hatched a dream of building a new venue for his Bullets closer to his D.C. home.

In order to secure the loans needed for his arena project, Pollin was also in need of a second tenant for the building. The Bullets would only occupy the venue for 41 nights each year, so Pollin - who had never seen a hockey game at that point of his life - set to the task of convincing the NHL's board of governors that Washington deserved an NHL expansion franchise.

It was a fortuitous time to be undertaking that task.

From 1942-43 through 1966-67, the NHL had been a six-team circuit in which no franchises failed or folded, and none moved to other locations either. This was in sharp contrast to the franchise expansion and nomadism seen in the other major pro sports during that time period. But with other pro sports leagues growing rapidly in size and scope with the advent of commercial air travel, the NHL finally followed suit in 1967-68, doubling instantly in size to a dozen teams. Two years later, Buffalo and Vancouver joined the League, expanding its ranks to 14 teams.

On November 8, 1971, NHL president Clarence Campbell announced the League's intention to expand its ranks to 24 teams by the end of the 1970s, a goal that would require the League to accelerate its already swift pace of expansion even further. This proclamation came on the same day that Atlanta and Long Island franchises were granted entry as the League's 15th and 16th teams, scheduled to start play less than a year from that date. Campbell's announcement came a week after the upstart World Hockey Association announced its 10 inaugural franchises for its first season of play in 1972-73.

When the NHL announced plans to add Atlanta and Long Island in November of 1971, it sparked a lawsuit from Long Island lawyer Neil Shayne, who had been granted a WHA franchise to play at Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale, NY, which was still under construction at the time.

"The purpose of the NHL expansion is to keep us out of the Coliseum," Shayne was quoted as saying in the Nov. 10, 1971 edition of The Montreal Star. "I intend to pursue vigorously whatever remedies are available to me under United States anti-trust laws."

The nascent league also announced its intent to put teams in Calgary, Chicago, Dayton, Edmonton, Los Angeles, Miami, St. Paul, San Francisco and Winnipeg.

According to the piece in The Star, Campbell claimed that the NHL had received expansion feelers from groups in Baltimore, Cleveland, Kansas City, Indianapolis, San Diego, Seattle-Portland, Denver and Columbia City, a new community near Washington, D.C., where Pollin initially thought of building the new arena. Given Campbell's stated intention to make the NHL a 24-team league by decade's end, even adding two new teams every other season wouldn't get the League to that objective until 1980-81.

In the tiniest of nutshells, that was the state of the NHL and the WHA in the early 1970s. Locally, the sporting landscape was dire. Aside from Washington's longstanding NFL franchise, there were no other major pro sports franchises in the District at the time.

Less than a year earlier, Major League Baseball's Washington Senators had pulled up stakes and moved to Arlington, Tx., where they would continue existence as the Texas Rangers. That incarnation of the Senators was the second to depart the District in less than a decade; the original Washington Senators moved west to become the Minnesota Twins in 1961. Those original Senators were replaced by an expansion team with the same name in '61, the team that ultimately split for Texas after the 1971 season.

The NBA hadn't been in D.C. since the 1950s, but the renegade American Basketball Association briefly had a team in the District after Earl Foreman suddenly bought and abruptly moved the Oakland Oaks here, just ahead of the start of the 1969-70 season. Renamed the Washington Caps, the team played just that '69-70 season in D.C. The Caps played their home games at Washington Coliseum - formerly known as Uline Arena - but attendance was weak. After their lone season in the District, the Caps bounced in a southerly direction once more, becoming the Virginia Squires.

The state of pro hockey in the District was even worse in those days. In 1973-74 - the season prior to the Capitals' entry into the NHL - there were five different minor professional leagues with NHL affiliations scattered around North America: the American Hockey League, Central Hockey League, International Hockey League, North American Hockey League and the Southern Hockey League. Each of those latter two leagues was conducting its first season in '73-74; both rose from the ashes of the newly defunct Eastern League, which shuttered after the '72-73 season, the end of a four-decade run.

In addition to the 16 teams in the NHL and the dozen operating in the WHA, those five minor pro leagues had a total of 40 teams among them, for a total of 68 professional hockey teams in operation, none of which was headquartered in Washington. Not only that, pro hockey hadn't had a home in the District since the aforementioned Eastern League's Washington Presidents moved to south Jersey to become the Jersey Larks following the 1959-60 season.

Ray Miron was the general manager of the Presidents in their final season in D.C. The Presidents missed the playoffs and moved on to Jersey, where Miron discussed some of his woes in Washington upon arriving in his team's new home in Haddonfield, N.J.

"The people in Washington all want to get something for nothing," beefed Miron to Frank Dolson in the Aug. 17, 1960 edition of The Philadelphia Inquirer. "You only get crowds if you give the tickets away. They used to get big crowds there in the '40s, but they had to paper the house to get them. And once people are used to going someplace for nothing, well, it's hard to break them of the habit."

Miron wasn't finished.

"We wanted to move the team out of Washington when we got it," Miron continued, "but the league wouldn't let us. Philadelphia had a vote then, and they didn't want us to come here. When they went bankrupt they lost their vote - and here we are.

"We did $69,000 worth of business in Washington last season. Philadelphia did something like $109,000. Yet they threw in the sponge and we kept going. Still, how do you go on competing with a team that takes in $40,000 more than you do?"

After playing the 1960-61 season in Haddonfield as the Jersey Larks, Miron and the team moved once again, this time to Tennessee where they became the Knoxville Knights.

Following the departure of the Presidents from the District in the spring of 1960, D.C. was without pro hockey for more than a decade, and this was at a time when the game was spreading far and wide, with multiple major and minor leagues in operation once the WHA began play in the fall of 1972. Pollin's task was to convince the NHL and its franchise owners that Washington deserved an NHL franchise more than the other applicants, despite hockey's long lack of success - albeit at the minor league level - in the city.

Following the announcement of the addition of Long Island and Atlanta to the NHL late in 1971, the League noted its intention to announce the next two expansion entrants in May of 1972. Pollin only had a few months to get his presentation together.

Jack Chevalier's column in the March 18, 1972 edition of The Baltimore Evening Sun - headlined "Pollin Ready To Take $20 million NHL risk - lays out Pollin's quest.

"The acquisition of a National Hockey League franchise for the Baltimore-Washington area has been said to be a $20 million gamble.

It would cost $10 million, at least, to build a 15,000-seat arena and another $10 million to purchase players and begin operations.

Until this week, nobody had expressed a willingness to take that $20 million gamble.

Now, Abe Pollin, owner of the Baltimore Bullets, wants to build an arena on the eastern edge of Columbia, near interstate 95, for the Bullets. But he realizes that such a building would lack firm financial footing without a hockey franchise as co-tenant.

"I can't build an arena without a hockey team, and the NHL would never grant us a franchise without definite plans for an arena," Pollin said.

The article also made mention of the population boom in suburban Maryland, noting that 5 million people resided within a 30-mile radius of Columbia at the time.

While Pollin was working on his pitch, his competition was doing the same in other cities across the continent. In addition to Pollin's bid for an NHL franchise, three different hopeful ownership groups from Kansas City were readying their own presentations, as were single groups from Cincinnati, Cleveland, Dallas, Indianapolis, Phoenix and San Diego. Aside from Indianapolis, each of those other cities had well-established minor league clubs already in town.

On May 2, 1972, The Baltimore Sun's Alan Goldstein reported that Pollin and his former Bullets partner Arnold Heft had reached an agreement to build a 17,500-seat in Prince George's County, on public land just off the Beltway. The article notes that the arena would be "… built on a 50-acre site acquired by Heft from the Maryland National Capital Park and Planning Commission."

"I have a 20-year lease on the land and two 10-year options," said Heft. "It's only three miles from the District line, but 45 minutes from downtown Baltimore.

"We could put an arena up by 1973. I checked with the builders in Minneapolis, and they put up a new arena in 13 months. If they can build that fast in sub zero weather, we should have no trouble if we break ground by August or September."

With the arena issue seemingly settled, Pollin needed only to hone his presentation and get ready for the big day. The eight prospective NHL cities were notified that final presentations and a decision would be made in New York on May 25 of that year. But the big day came and went with no decision from the League. The presentations were made, but the League needed time to absorb them all.

The May 26, 1972 edition of The Baltimore Sun quoted Campbell on the situation: "The presentations by the 10 groups was beyond the digestion of the governors in the league. There was a tremendous amount of statistical information made available. Anything less than a thoughtful consideration would be an injustice.

"I doubt that in any expansion in professional sport has one league been so fortunate to receive so many exceptionally qualified applicants. Frankly, when we announced for further expansion in 1974, we anticipated applications from approximately four cities. The fact that we received 10 applications from 8 cities (three from Kansas City) was certainly the strongest indication of the growth and acceptance of hockey in North America. I must say that we consider this a pleasant problem."

The NHL deferred its decision until June 8, when the League and the governors would meet again in Montreal for the 1972 amateur draft and the expansion drafts to stock the Atlanta and Long Island clubs.

Most impartial observers saw Kansas City as a slam dunk to get one of the two new teams; it was merely a question of which of the three prospective ownership groups would get the franchise. From there, opinions varied. But most expected either Cleveland or Cincinnati to get the other expansion franchise for 1974.

Meanwhile, other developments added a new wrinkle to Washington's prospects for an NHL franchise. Noted maverick Charlie O. Finley, owner of the NHL's California Golden Seals and MLB's Oakland A's, was casting about for a potential new location for his hockey team, which was losing money hand over fist in Northern California.

Washington was absolutely interested in having the A's move to D.C. to replace the Senators, who departed the District for Texas less than a year earlier. But for Finley, it was going to have to be an all or nothing deal. Any potential new home for the A's - who would win the first of three consecutive World Series titles in the fall of '72 - would have to take the Golden Seals as well.

Legendary baseball writer Shirley Povich wrote about Finley's situation in The Washington Post, and a syndicated version of that piece appeared in the June 6, 1972 edition of The Charlotte Observer. Povich claimed that if Pollin got one of the two NHL expansion teams, it would hurt the District's chances of getting baseball back.

It would deny to Washington the city's best chance of luring another baseball team here. The most-available, and perhaps the only available, baseball franchise is that of Oakland, where Charles O. Finley also owns an NHL hockey franchise. He is hankering to move both to Washington.

Only if Washington is still an open city in hockey, without a franchise, can Finley and his baseball and hockey teams be attracted here. He will move them only in tandem. Finley recently told a friend, "You can guess what they'd do to me here in Oakland if I moved the baseball team and left the hockey team. They'd cut my heart out."

Campbell poured cold water on the whole idea of Finley moving his clubs across the country to Washington.

"In the 57-year history of the NHL we've never shifted a franchise," said the League's president. "It would take a unanimous vote and I am certain it won't happen."

It didn't happen then, but it would happen soon. The Golden Seals shifted to Cleveland for the start of the 1976-77 season, briefly becoming the Cleveland Barons.

On the morning of June 8, The Minneapolis Star's Dan Stoneking reported that the League was considering adding four new teams instead of two, potentially taking two more cities away from the clutches of the WHA, which was charging franchise fees of just $250,000 per team as opposed to the $6 million the NHL would be getting from its newest members.

"What amazes me is that there is so many groups with all that money wanting into hockey," said one anonymous member of the NHL Board of Governors.

The Indianapolis group already had its arena under construction. The city had an original ABA franchise - the Pacers - and was seeking a co-tenant for its 16,000-seat, $17 million arena.

Asked if the process was worth all the grief and expenditure, lawyer Dick Tinkham - a representative of the Indianapolis group - answered in the affirmative.

"Obviously," he said, "or I wouldn't be here. We've had several offers to get into the World Hockey Association. But I've had it with new leagues. I'd rather give the NHL $12 million than go through all the crap I've had with the ABA for the last five years.

"New leagues just cannot make it. In the ABA right now, we're weeding out the soft spots, hoping to wind up with four or five solid cities. The WHA will have to suffer through the same agonies. They won't even have a real league for four or five years, and by then they'll be down to three or four strong franchises."

Tinkham was right on all counts. The ABA wound up with four solid cities that merged into the NBA a few years later. The WHA suffered through a litany of agonies on and off the ice, lasting seven years in total and ending up with four "strong" franchises that merged into the NHL in 1979-80.

In 1973, Indianapolis tried to buy and move the Golden Seals to Indiana, where Finley maintained residence. But the NHL Board of Governors shot down the sale, and Indy had to settle for a WHA franchise from 1974-78. A 17-year-old phenom named Wayne Gretzky made his pro debut with the WHA's Indianapolis Racers in 1978-79, playing eight games with the Racers before the destitute team sold his contract to Edmonton. The Racers folded midway through that '78-79 season, the final campaign of the WHA's existence.

Given the extra two weeks, Pollin had been able to marshal some political support from back home. Politicians such as Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy and Senate minority leader Hugh Scott each sent telegrams to various members of the Board of Governors, singing the praises of the Pollin bid.

Scott's wire threw another new wrinkle into the mix, the possibility of a downtown D.C. arena.

"It is my understanding that the public buildings subcommittee of the House Public Works Committee has already approved by a resolution a proposal for a convention centre sports arena to be located within the District of Columbia. The center would be financed with a 30-year guaranteed federal lease," it read, in part.

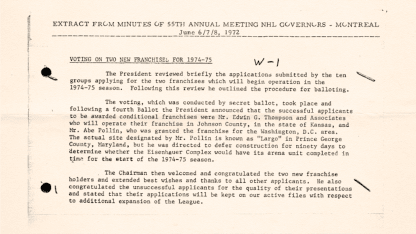

Voting was conducted by secret ballot, and approval required 12 votes from among the 16 existing clubs. (That total includes Atlanta and Long Island teams, which had just conducted their expansion draft two days earlier and would be participating in their first NHL Entry Draft on June 8 as well.) Balloting was done "convention style," with the last team in each ballot eliminated until only two remained.

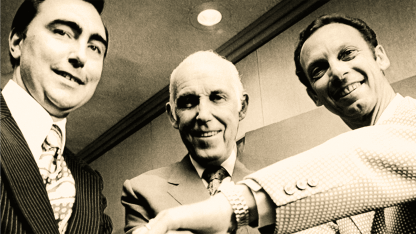

Four ballots into the process, a verdict was reached.

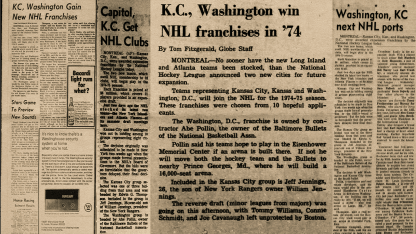

"We are pleased to have Washington and Kansas City join our National Hockey League family and it was really gratifying to have received so many strong applications," said Campbell. "We have selected two very strong and attractive cities. However, the selection of these two cities from among all the outstanding applications was an extremely difficult decision.

"In November 1971 we announced the intention of the NHL to expand to as many as 24 teams in North America in the 1970s. We will vigorously pursue this long-range plan of growth in an orderly manner and accordingly we consider the remainder of the applying cities as continuing and strong candidates for NHL franchises in our future expansion."

Ironically, among the six cities whose bid fell short 50 years ago, none has ever been granted an NHL expansion franchise. Cincinnati, Indianapolis and San Diego all remain untapped NHL markets, while Cleveland, Dallas and Phoenix eventually landed teams via the relocation of existing franchises.

"I was very happy," says Pollin in the June 9, 1972 edition of The Baltimore Sun. "It's something I've wanted and fought for for a long time. I should be happy."

Happy and tired. Pollin said he didn't sleep more than two hours on any of the five nights leading up to the vote.

"I'm going home (to Bethesda) to get some sleep," he added.

Pollin's successful bid was based on the downtown D.C. arena plan to which Scott's telegram alluded; the NHL wanted Pollin's team to be in the District and to play its games at The Eisenhower Center, as the project soon became known. It's even possible that planting the seed of the possibility of a downtown arena aided Washington's successful bid for a team. But Pollin knew his business well, he knew red tape and bureaucracy well, and he also knew that time was short if he was going to have his arena built and ready in time for opening night of the '73-74 NBA season.

Pollin allowed the League and its governors to briefly believe in the fantasy of a downtown D.C. arena, but he also doubted the ability of the government to act swiftly enough to fund the project and break ground soon enough for the building to be ready on time. Accordingly, he agreed to defer the start of construction at the Largo site for 90 days, giving the Eisenhower Center a chance to get off the ground, which it never did.

"I doubt very much the new downtown arena could be authorized in time," Pollin was quoted as saying in a June 10, 1972 Associated Press story. "The downtown arena would require $100,000,000 of public money. An arena in Largo would not require as much, and it wouldn't involve uprooting private families, public businesses and religious institutions."

On Aug. 1, 1972, ground was broken for construction on the building that would be known as the Capital Centre.

One area where Pollin did not waver - at least not in 1972 - was on the viability of the Washington market to support an NHL franchise.

"The market potential there is fantastic," said Pollin in a June 9, 1972 article in The Calgary Albertan. "We've had surveys taken and if we were starting tomorrow the surveys show we could sell 26,000 season tickets."

Fifty years down the road, the Capitals are playing in a downtown D.C. arena where they will celebrate their 25th anniversary late this year. They have a host of ardent fans around the globe, thanks to a game and a League that's gone global in its reach over the last half century. The Caps celebrated the fourth anniversary of their first Stanley Cup championship on Tuesday, a day ahead of their 50th birthday.

Pollin passed away in 2009 at the age of 85, a decade after he sold the Caps to Ted Leonsis and two years after the 600 block of F St. NW was renamed "Abe Pollin Way" in his honor. Pollin's vision and his persistence brought the Caps to life 50 years ago at Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal (now Fairmont Queen Elizabeth Hotel), and although the team missed the playoffs in each of its first eight seasons of existence, it has missed only eight times in four decades since.

Looking back, it's astounding that Pollin was able to convince the League's power structure to grant Washington a franchise in the first place, given that the city had a dubious hockey history and had been without the game for a decade and a half. And given the on-ice trials and travails of the early years, and the frequent franchise movement the League saw - starting in 1976 when the Kansas City Scouts moved to Denver to become the Colorado Rockies - it's impressive that the Caps have stayed here in the area for the last half century, too.

From 1967 to 1979, the NHL added a whopping 16 franchises to what had been the Original Six for so many years. A dozen of those additions came via expansion, and four more came when the League absorbed four WHA franchises at the outset of the 1979-80 season. Of those 16 franchises, Washington is one of nine still remaining in its original location.

Over those 50 years, we've seen the Caps go from registering just eight wins in 80 games in their first NHL season to having the most memorable No. 8 in League history in Alex Ovechkin. We're excited to see what's on the horizon as the next half century of hockey history in the District unfolds before our eyes. Happy birthday to the Caps, and many, many more.