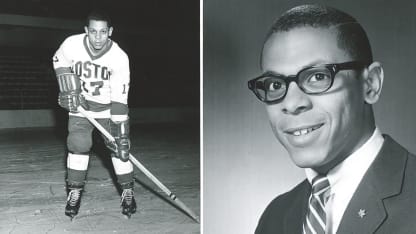

On the ice, Eddie Wright was a talented hockey player. Off the ice, he was a talented hockey mind. Growing up and playing hockey in the 1950s and 1960s however, there weren't many people like Wright in the game; not only because of his skill, but also because he was Black.

Former Ducks Scout Wright Was a Hockey Trailblazer

Among the barriers Wright broke in his career, he is believed to be the first Black scout in NHL history when he joined the Ducks staff in 1994

By

Ian Kennedy / Special to AnaheimDucks.com

Despite facing racism at each step of his career, Wright would become the first Black player on his Junior team, a star with Boston University, the first Black hockey coach in NCAA history, and one of, if not the first, Black scout in NHL history when he was hired by the Anaheim Ducks in 1994.

Like many Canadians, Eddie's love for the game blossomed in a friends driveway playing street hockey.

"We were out there every day," recalls Wright. "After school we were there with the rubber ball, and we were going at it until we lost the ball in the dark. It was competitive. Those were real dreams we were living when we were going through that, and we were hard at it."

His two best friends growing up, were Mel and Herb Wakabayashi, who would both go on to play Junior, and in the NCAA, as well as the Olympics for Japan. By 1963, the trio were playing together as a potent line for the Chatham Jr. Maroons.

While they each faced racism, it was Wright, the first Black player in team history, who took the brunt of the hate from his opponents, and those in the stands.

"I think I got it worse because skill-wise, they were just unbelievably fantastic athletes," Wright said. "Myself, being Black, and being five-foot-three-and-a-half, and 138 pounds, I had to be tough, physically and mentally."

While his white teammates prepared for a game, Eddie Wright prepared for battle. That's what he called it. To him, the game, and what it took to play, was serious. It didn't matter what town he went to-Leamington, Detroit, London, or his hometown of Chatham-Wright had opponents on the ice and opponents in the stands. "It was whatever it takes to win, and the fans certainly threw the insults at me left, right and centre. The players on the ice were worse. I pretty much fought all throughout Junior."

It got so bad Wright developed an ulcer in his final year of Junior hockey, and refused to allow his family to attend games, knowing what they would see and hear.

"I didn't really want anybody who I thought really cared about me and loved me - family - there to see what I was going through, because it wasn't easy."

Eddie's sister Dorothy felt bad about not supporting him. She recalls, "I felt guilty, and went to my brother and said, 'Eddie I'm sorry that I didn't go and see you play hockey,' and his answer really kind of took me aback. He said, 'I'm glad you didn't.' He said, 'I had a job to do on the ice, and I'm glad I didn't have to worry about putting up a fight and getting you out of something up in the stands. I couldn't have handled that.' I felt better hearing that, because I would have started trouble. There were a lot of racial slurs thrown at him."

Despite the hardships, Wright's talent was undeniable, and earned him a scholarship to Boston University. There he joined his childhood friend Herb Wakabayashi yet again on the ice. The duo formed one of the most best penalty killing units in the NCAA, pinning the opposition deep in their own zone. At one point, Herb and Eddie killed 36 consecutive minutes of penalty time without allowing a shot on goal.

Wright was impactful on the ice, but it didn't change one overriding fact - Eddie Wright was a Black man. In his sophomore season, Wright was replaced as Herb's winger, and he knew why.

"That was a devastating time for me," he said. "I wasn't playing, I wasn't dressing for games, in practice I was on the fourth line. It was quite evident I should have been in the lineup. I kind of thought that it had something to do with the color of my skin, I thought the color of my skin was overshadowing my skill as a hockey player. I was very, very angry. I was an angry man for a whole year."

Eddie however, persevered.

"I hung in there. In the long run it was good for me, a very valuable lesson, not only about my skill as a hockey player, but as a Black man in the world that I was dealing with."

That season, Boston lost in the national championship to Cornell, who were backstopped by a future Hall of Fame netminder named Ken Dryden. Despite the fact Wright could have helped Boston, he remained sidelined.

The following season he finally got his chance. "I managed to get in the lineup in my junior year, and I was very successful. I was very productive member of the team. At the end of my career, Jack Kelly, my coach, openly admitted to me that I was one of the biggest mistakes that he ever made."

After his college career, professional hockey was not a consideration for Eddie Wright. He wanted to be a physical educator, a teacher. In 1970, just as he was finishing his Master of Education degree at Boston University, he received a call from the State University of New York at Buffalo. Buffalo had a hockey team but wanted to take it to the varsity level. If the school could find a Black hockey coach, the costs would be covered by affirmative action funding. Overnight, Wright became the first Black coach in men's NCAA hockey history.

According to Wright, serving as a coach did not protect him from the same abuse he had experienced as a player. "Racist taunts and gestures occurred at road games" and he also recalls fans "chanting a racist and homophobic slur" at him.

The racism Wright faced throughout his career left its mark. "Hearing the crowds chanting, it wasn't easy," Wright told The Buffalo News. "It wasn't easy. To this day I think it has an everlasting effect on the type of individual I am and how careful I am about where I go and how I deal with things."

Wright spent 17 years working as a coach at Buffalo, until stepping down in 1987. A few years later, Wright called a former Boston University teammate, Jack Ferreira, to congratulate him for being hired as General Manager of the then Mighty Ducks. A week later, Ferreira called back. He wanted to hire Wright as a scout serving Ontario and western New York. In 1994, Wright joined the Ducks scouting staff.

It was a door that until now, had remained closed for Black men in the NHL. Willie O'Ree, the NHL's first Black hockey player wanted to be a scout when his career ended: "I tried and tried, but those doors never opened for me," he said about entering scouting.

Bill Riley, the third Black player in NHL history echoed these issues following his retirement from hockey in the 1980s

"I could never get through the door. I can't even get a job as a scout," Riley said of attempting to find a job at the NHL level.

It makes the Ducks' decision to hire Eddie Wright in 1994 even more important.

One of Wright's notable discoveries scouting for the Ducks was Steve Rucchin, who was playing hockey at a Canadian university at the time but would go on to have a notable career with the Ducks, spending 10 seasons with the franchise, including serving as captain in 2003-2004. Wright spent five seasons scouting for the Ducks before retiring.

Since then, his impact has been recognized many times over, including in 2010 when the State University of New York at Buffalo opened the Edward L. Wright Practice Facility to honour their famed coach. In 2014, he was inducted into his hometown Chatham Sports Hall of Fame. This month, he will be inducted into the SUNY-Buffalo Sports Hall of Fame.

Happily retired and living in Arizona, hockey is behind Eddie Wright, but in his wake, he left an impactful legacy, trailblazing a path for Black players, coaches, and scouts, including his important part of Anaheim Ducks history.

A resident of Erie Beach, Ontario, Ian Kennedy is an educator and journalist. The founder of the Chatham-Kent Sports Network, Ian is a contributor for The Hockey News and Outdoor Canada. Ian's debut book, "On Account of Darkness: Shining Light on Race and Sport" will be published in May 2022 by Tidewater Press, and is available for pre-order now.