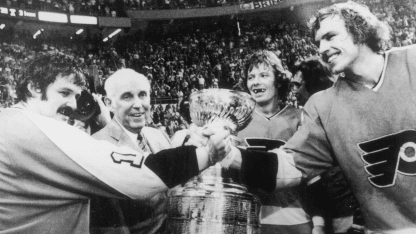

Something that often gets overlooked about the Philadelphia Flyers teams of the mid-to-late 1970s is that apart from winning back-to-back Stanley Cup championships in 1974 and 1975, making three straight Cup Final appearances (1974, 1975, and 1976) and their utter dominance on home ice, the team was a perennial Cup contentender even when they didn't capture hockey's ultimate prize. Head coach Fred Shero guided the Flyers to at least the semifinal round for six straight seasons (1973, 1974, 1975, 1976, 1977 and 1978).

45th Anniversary: Flyers Capture 2nd Straight Stanley Cup