When William Arthur Torrey was a young whippersnapper of 12 years old living in Montreal, he had a simple wish.

"I want to play for the Montreal Canadiens."

That's what the Bill Torrey of 1946 would muse about over and over again. And since Canada is a free country, Young William Arthur was entitled to his fantasy.

Maven's Memories: Bill Torrey's Road to the Islanders

The origin story of the Hall of Fame General Manager Bill Torrey

© B Bennett/Getty Images

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

After all, the man who would someday build the New York Islanders into the greatest hockey team in National Hockey League history lived a mere slapshot away from The Forum, home to the then world's best team, Les Habitants.

The Habs, had just won the 1946 Stanley Cup and featured a train-load of heroes for this young fellow to idolize.

"Well, there was The Rocket (Maurice Richard) who was like the Babe Ruth of Hockey," Bill remembered. "And he played alongside Elmer Lach at center and Toe Blake on the other side. They were called 'The Punch Line' and I loved 'em.

"But that wasn't all. Our goalie, Bill Durnan, already had won three Vezina Trophies and was considered the best in the world. On defense there was Kenny Reardon who was about as tough as (fight champ) Joe Louis."

When Bill told his stockbroker dad, Arthur Torrey, that he could see himself wearing the bleu, blanc et rouge (blue, white and red) of Les Habs there were no objections. After all, pop knew that his lad had the goods to be a player.

Young Torrey's climb up the hockey ladder began seriously in high school at Vermont Academy in Saxtons River where he captained the hockey team.

MAVEN'S MEMORIES

WRITTEN COVERAGE

The Heals and Flats Show

1993 Run Ends in Montreal

Unusual Draft of 1979

Isles Upset Pens in 1993

Prelude to Penguins Upset

Isles Beat Caps in 1993

1992-93 A Season to Remember

Making News in 1991-92

Maven's Haven

"Bill couldn't have been too bad a player," said his Islanders future colleague Jim Devellano, now Executive Vice President of the Detroit Red Wings. "He never made the Canadiens but got a hockey scholarship to St. Lawrence."

The collegian Torrey was pretty darn good too. He played in two NCAA hockey championships for the Saints but was ineligible to play hockey in his senior year at St. Lawrence.

Torrey: "As a player, I was far from the best. I can only tell you no one loved playing more than I did, and no one competed harder."

He finished his university career announcing games on the radio and thinking about his future. It was around this time that he began wearing bow ties. The budding Beau Brummel eternally would be known as "Bow Tie Bill."

He could thank his father, Arthur, for that. It was the senior Torrey who inspired Bill to eschew regular cravats. Arthur Torrey claimed that ordinary ties interfered with his work.

"Eventually, I asked dad how to knot a bow tie and he showed me the trick," Bill recalled. "After that I wore only bow ties and over the years, unsolicited, people would send me bow ties. I always carried one with me."

He showed the hockey folks at St. Lawrence that he had a surplus of skill but what he lacked was luck. Because of a career-ending ice injury it remains to this day hard to project just how far Torrey might have ascended as a player.

"I took a stick in the eye," he winced, "and it broke my orbital bone and that affected my vision to the extent that being a pro hockey player no longer was a realistic goal."

His majors at St. Lawrence -- psychology and business -- later would prove valuable. Re: hockey, Bill's psych courses were useful since his first NHL boss in Oakland, Charlie Finley, was an acknowledged head case.

His business studies at St. Lawrence also would be useful once he dove headfirst into the world of managing hockey teams. But, after graduating from university, Torrey wasn't sure how his roulette wheel would turn.

Just for kicks -- and to see what was what -- he decided to take a bite out of The Big Apple and the Apple almost bit him back.

"I got a job as tour guide with NBC Network at Rockefeller Centre," he chuckled. "The problem was that I didn't concentrate and was always getting the tours lost."

Rather than fire this bright, bow-tied young man, Bill's boss switched him to office work at which time an interesting tourist briefly -- but significantly -- entered the scene. Her name was Lady Luck.

As Ms. Luck would have it, a fellow named Walter Brown dropped over to the RCA office. Brown, a well-known Boston hockey executive, had remembered Torrey from the Saints ice lanes so, naturally, they started talking pucks.

Once Young Torrey made it clear that he wasn't planning to be an ex-tour guide forever, the eminent and well-connected Mr. Brown said he'd help Bill get a better job. And he did; but not in New York or Boston -- in Pittsburgh.

Torrey: "Brown contacted John Harris, who owned the Ice Capades, a successful travelling show. Plus, Harris had other businesses and he invited me to his Pittsburgh office to work for the Capades and a few different things."

Among those "other things" were jobs such as doing publicity for the minor league Pittsburgh Hornets. Bill not only learned PR, but also business affairs, marketing the Ice Capades and other arena events.

Lady Luck continued following him around and this time she managed to push Bill's foot into an NHL door. It was after the NHL had expanded from six to a dozen teams for the 1967-68 season and the Oakland Seals was one of them.

"The Seals were an ownership mess from the get-go," Torrey opined, "and needed some outside help. That's where I came in -- almost by accident."

Torrey was asked by Potter Palmer, one of the original Oakland owners, to pinch-help the beleaguered franchise. Bill obliged, once even repping the Seals at an ultra-serious NHL Board of Governors meeting.

Torrey: "I was basically an onlooker as the owners talked about a second expansion involving Buffalo and Vancouver. For me, it was a chance to meet some of the big names in the business.

"Some of the talk was about how much to charge the new teams and they finally agreed that it would be $6 million per team to get in. That persuaded the skeptics, like Stafford Smythe in Toronto, to approve the new owners."

Meanwhile, Bow Tie Bill's managerial skills were being noticed outside the ice world. One outfit, Lever Brothers Soap, offered him a good job but he washed his hands of that. He sealed his fate by accepting the GM job in Oakland.

"And to think," Bill laughed at the retrospective thought of it, "I could have become a soap salesman."

Poof! He was Seals boss -- or so he thought -- in 1968, the second year of NHL expansion. The Seals, now owned by controversial baseball empresario Charlie Finley, seemed like a good fit for Bill, but Finley would prove to be un-fit.

Lady Luck had gone bye-bye on Bill and now he was forced to go one-on-one with Mister Moneybags Finley; and Torrey lost.

"I was supposed to have control of the team and players," Bill remembered. "I had all the contracts on my desk one day and they were supposed to be mailed out that night.

"Charlie told me not to mail them. I told him there was a deadline and he said, 'Forget that baloney.'"

Bill had to make a decision: keep the job and lose his sanity or quit the job and maintain his marbles.

Bill exited Stage Right with a terse note to Finley. "Dear Charlie O. I want to put this letter in terms you understand, so blankety-blank you, I quit."

Torrey skedaddled back to Pittsburgh until 1972 when there was yet another NHL expansion -- Long Island and Atlanta joining the ice fraternity -- with a chap named Roy Boe purchasing the Uniondale-based franchise.

Since Boe didn't know much from pucks and needed a general manager he contacted a couple of his buds; one being respected broadcaster Tim Ryan, who had worked for a time in Oakland alongside Bow Tie Bill.

"Take Torrey," Ryan told Boe.

"Who's he?" replied Boe, proving he was less than a hockey maven.

Tim clued in Boe so Roy then turned to Nelson Doubleday, who had been a minority owner of the Seals. Doubleday immediately seconded Ryan's motion.

As a result, Torrey bought a one-way ticket to LaGuardia Airport and then hopped a cab to Long Island and his first sane full-time job in the National Hockey League.

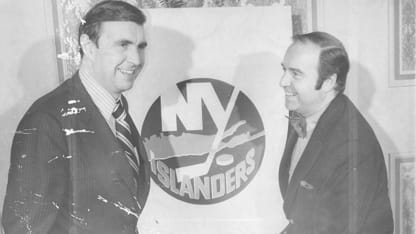

© New York Post Archives/Getty Images

In retrospect, the Finley Follies as well as Torrey's American Hockey League experience handling contracts proved invaluable to him as the Islanders first boss.

And speaking of contracts, a favorite Torrey story is told by Bill's eldest son, Rich, who knew about his father's work in Pittsburgh.

Rich Torrey: "Dad got a call from (then Red Wings GM) Sid Abel telling him a player was coming to Pittsburgh and that Bill should give him a minor league contract. The guy shows up at the arena and Dad shows him the contract.

"The guy says he's not going to sign for that amount and eventually leaves. A little while later he comes back and asks my dad if the Red Wings would pay for his flight out of Pittsburgh. Dad told him no, so the guy signed the contract."

The fellow happened to be career minor leaguer Doug Messier, father of Hall of Famer Mark Messier. It also was the first contract Torrey ever negotiated.

Bow Tie Bill's own first Isles' contract meant that his youthful dream of making it really big in the NHL was realized but not as a player. In a sense being GM was even better; or as comic Mel Brooks once said, "It's great being king."

But, whoa! This monarch had his work cut out for him beginning with a staff of exactly none. He put out an S.O.S. in the hockey world and got results.

A secretary was a starter. It just happened that Estelle Ellery, wife of AHL publicist Jim Ellery, was a hockey wife who knew the difference between a puck and a social tea biscuit. Frau Ellery was Bill's first hire.

Next would be a talent maven -- a solid bird dog who would work with a limited budget. Estelle was closely followed by ex-NHL goalie Ed Chadwick who'd be Bill's first aide de camp.

Torrey's next -- and arguably best -- hire happened by accident. Walking along Montreal's Ste. Catherine Street West with Chadwick, they bumped into a young Torontonian in search of a scouting gig. His name was Jimmy Devellano.

"I shook their hands," Devellano recalled, "and we had a chat. It might sound ridiculous for me to say that I was basically hired on the street but that was pretty darn close to what happened."

Torrey: "Jim Gregory (Maple Leafs GM) had told me about Jim and said that he had done a pretty good job scouting for the Blues. I wound up making a deal with Jimmy for him to be our Eastern Canada scout."

"From the very start," added Devellano, "Bill was gracious to me. He was polite, a quality he exhibited his entire life."

Building an expansion team in 1972 was about as easy as scaling Mount Everest, backwards. Not only was Torrey competing with newly-formed Atlanta but the World Hockey Association also had arrived and was stealing players.

"By the time the WHA got through raiding our players," said Devellano, "we had lost seven of them. We still wound up drafting Billy Harris and later Bill Smith. Still, at the end of our first year Atlanta finished with 65 points to our 30."

But there was a sweet use in Bow Tie Bill's adversity. When it was time for the next (1973) Draft, the Isles were guaranteed first pick among the young prodigies.

Devellano had scouted defenseman Denis Potvin and told Torrey that the kid from Ottawa was "One of the best Junior players I'd ever seen." And Jimmy D had seen a plethora of prodigies.

A Night Celebrating Bill Torrey

Trouble was that some WHA teams thought so, too. Now Bow Tie Bill had to figure a way to ensure that Denis signed his pact in Uniondale not with the WHA New York Raiders or New England Whalers.

Eureka! Bill had a foolproof plan; sign Denis Potvin's older brother, Jean, and that would induce Denis to forsake the WHA for the NHL.

Torrey: "Jean was playing for Philadelphia so I contacted the Flyers manager, Keith Allen, and made a trade with him. I sent Philly a solid, veteran forward, Terry Crisp, for Jean and then invited Johnny's parents to visit Long Island."

Jean talked to Denis. His parents talked to Denis and what once looked like a major problem for the Isles became a no-brainer. Denis Potvin would sign on with the Nassaumen if Torrey still had the first pick.

Not surprisingly, a couple of other NHL clubs -- namely the Canadiens and Rangers -- still angled to make a deal with Bill for that first pick. Habs GM Sam Pollock put the most pressure on a few hours before the actual Draft.

"This was at the Mount Royal Hotel in Montreal," Torrey smiled, "and Sam asked that we go outside and take a walk. We circled the hotel three or four times and Pollock told me what he'd offer for my pick.

"He had a bunch of names but I told him that if he'd give me a Rocket Richard or a Jean Beliveau I might change my mind. I said, 'Sam, I'm not trading my pick.' (Rangers GM) Emile Francis also had an offer but I wanted Denis."

In his autobiography, "Power On Ice," Potvin revealed that right up until the moment of the Draft itself, he was worried that the Habs would swing a deal for him. Denis insisted that he wanted to be an Islander and Torrey came through.

"Now," said Devellano, "Bill had gotten us a star to build our team around. We had our first big building block and it was thanks in part to Bill's trade with the Flyers."

But there remained a second building block to obtain; that would prove as important as the acquisition of Denis Potvin.

While the Potvin pick was as easy as plucking cherries off a tree, selection of a coach -- both Phil Goyette and Earl Ingarfield couldn't lift the Original club -- was a puzzler for Torrey.

In Devellano's autobiography, "The Road To Hockeytown," Jimmy details the choices confronting Torrey. Johnny Wilson was one and Johnny McLellan was the other. Jimmy told Bill that he liked them both.

Jimmy D: "But there was a guy I liked a little better. This guy had two short shots at coaching the Blues but never got a chance to really show what he could do. I thought Al Arbour would be a good choice for the Island.

"I knew Al from my days in St. Louis and told Bill to include him in the interview process and he did. Now we had three choices and Bill began leaning to Al."

Torrey also checked on Arbour with Scotty Bowman who had Al on his St. Louis sextet. "I asked Scotty what he thought of Al," said Bow Tie Bill, "and he told me there was an ownership problem in St. Louis with the team.

"Scotty told me that he couldn't say enough good things about Al. He was captain; he stood up for his players and he stood up for the right way of doing things. He added that Al would be a heck of a coach for us."

But Torrey also learned that Al's wife, Claire, took a dim view of Long Island. She labored under the misapprehension that it was a madhouse like Manhattan. Claire didn't think The Big Apple was the place to raise her family.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

"I invited Al to the Island for an interview," Torrey explained, "and showed him around Nassau and Suffolk and potential neighborhoods. Once he saw how beautiful it was that clinched it for both Arbours."

One other positive element played into this franchise-changing decision and it all had to do with The Boss, Bowtie Bill, and the positive effect that he had on virtually every person he encountered.

"Put it this way," Devellano added, "to get Al, there was also a matter of how he'd feel about working with us. In the end, Al felt good about Bill. Bill had that effect on many people."

One anecdote underlines the point. A young man named "David" wrote this note about The Bow Tie Bill effect on people; namely himself:

"When I was ten my family was having dinner at Dr. Generosity's (restaurant) when my dad noticed Torrey eating with friends. We didn't have anything for Bill to sign but dad approached him and asked if I could say hello.

"Bill walked over to our table and spoke to me for a couple of minutes, asking who my favorite players were and thanking me for supporting the team, before going back to his dinner."

This was Bill Torrey, a man of all things good to all people, including his father, Arthur Torrey.

"Even after I got to the Island and was managing the team, Dad kept asking me when I was going to get a 'real job,'" Bow Tie Bill concluded.

Job, schmob. This once-puck-mad kid from the sidewalks of Montreal built the greatest team in hockey.

And that was some real job!