Gerry Hart knew all about the subterranean depths.

As a teenager, growing up in the northerly reaches of Manitoba, he helped his father who worked in the mines. Deep, deep and deeper.

This was in the town of Flin Flon -- a story in itself -- where the Hudson Bay Copper and Zinc outfit was the company town.

Maven's Memories: Gerry Hart, the Heart of the Original Islanders

Stan Fischler profiles one the heart-and-soul defenseman of the 1970s Isles

© B Bennett/Getty Images

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

Flin Flon became notorious for many things including the weather. Heck, it's 500 miles north of Winnipeg, perhaps the coldest city on the NHL circuit.

For 35 years, Gerry's dad plumbed the depths and it was not fun work. Young Hart knew all about it, having helped out during the summers.

Canadian author Paul Rimstead once visited Flin Flon during Gerry Hart's time there and summed up the prevailing attitude this way:

Rimstead: "What's entirely different in Flin Flon is the attitude. Education? Phooey. If a kid played for Flin Flon, he'd quit school. He'd be a pro. He'd work four hours a day underground in the mine and practice.

MAVEN'S MEMORIES

WRITTEN COVERAGE

The Parise-Drouin Trades

The Great Smitty and Gretzky Battles

From Long Island Arena to UBS Arena

Isles-Rangers Feud: Heating Up Into the 1990s

Isles Sweep Rangers in 1981

Road to 1981 Cup, Round 2

First Steps Towards 1981 Cup

From Viking to Uniondale, the Sutter Bros

Bob Bourne's End to End Rush

Maven's Haven

"In fact, the school board would not even accept a player in high school. For one thing, a kid like Gerry Hart would be away on a bus all the time. Flin Flon couldn't have cared less what outsiders thought. The town wanted a team and the mine made certain that it had a team."

The mine went down 5,000 feet and had 50 miles or more of underground tracking on 70 different levels.

"It was a hard life," Gerry remembered, "but it was a living; except not what I wanted. And not what some of my buddies wanted either. And that included Bobby Clarke and Reggie Leach."

The trio agreed that life would be a lot more worth living if they could sidestep Hudson Bay Copper & Zinc for Flin Flon's hockey sticks and pucks. That wasn't necessarily easy work but darn better than the mine.

Hart and his pals learned to skate at Lakeside Park, an open-air rink. The kids skated there morning, noon and night. If there was ice, they'd be practicing.

"We had a Junior team in Flin Flon and a good one, too," Hart remembered, "and eventually I wound up playing defense for the Bombers."

In 1957 the Bombers reached the Memorial Cup final against Sammy Pollock's vaunted Hull-Ottawa Canadiens, the Junior farm club of the NHL Habs.

Somehow, the underdog Bombers beat the Canadiens and became the talk of the hockey world. Not surprisingly NHL scouts had their Argus eyes on players like Hart, Clarke and Leach.

Western Canadian Junior teams had a reputation for being tough but the ones from Flin Flon always seemed a high stick or two tougher than the others.

"It was the environment," said Islanders General Manager Bill Torrey. "You had to be tough to survive the conditions in Flin Flon."

Part of that rugged environment was Hart's home rink, the 2,000-seat Flin Flon Arena. It was frontier-style with a capital F. Author Rimstead once watched a game there when Hart played and loved it.

"You sit watching a hockey game in Flin Flon Arena," said Rimstead, "and you'd say to yourself, this is what hockey is all about. This is hockey before sophistication, before people started talking about this newfangled thing called education. This is hockey as it used to be."

Playing for the Bombers in those days unspoiled Hart; if there ever was any spoilage in him. For Gerry and his teammates, their nearest opponent was 500 miles away in Winnipeg.

"That meant a 10-hour bus ride," Hart recalled, "night and day. We got very tired near the end."

But the prospect of endless, boring bus rides never bothered Gerry because he was honing his game to what would eventually become major league sharpness.

That would come later. For starters, Hart had to earn a reputation in a town of 10,000 right plumb on the Manitoba-Saskatchewan border.

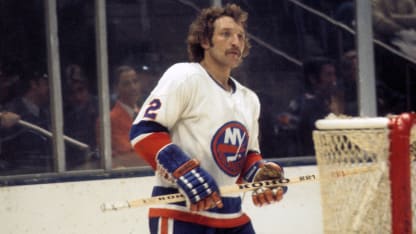

© B Bennett/Getty Images

Flin Flon itself was a marvel. It got its name -- believe it or not -- from a 1905 English dime novel. The hero's name was Josiah Flintabbatey Flonatin.

The novel, "The Sunless City," was discovered by a prospector Tom Creighton who discovered rich ore, staked the land, and called it Flin Flon from the novel's main character. Like other of the town's kids, Gerry knew the story.

By the time he was ready to graduate from the Junior Bombers, Hart was ready to leave the mine town and seek his fortune in professional hockey.

The Red Wings liked the looks of him, and by the 1970-71 season, he played his first full season in the bigs on Detroit's defense.

"Gerry was rough around the edges," said current Red Wings Executive Vice President Jim Devellano, who then was a St. Louis Blues bird dog. "But he was tremendously motivated."

When the Islanders and Atlanta were admitted to the NHL for the 1972-73 season, Torrey not only was competing against the Flames in the Expansion Draft but also the newly-competitive World Hockey Association.

"I wound up with three serviceable players," Bow Tie Bill remembered "and they were Eddie Westfall from Boston, Billy Smith from LA. and Gerry Hart from Detroit. Each one would play a part in our success, but not right away."

Hart would become a crowd favorite at the spanking new Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum. He stood out because of his physical presence and style, which pleased the blue-collar crowd.

"Gerry backed away from no one" recalled Associated Press sportswriter Shelly Sakowitz. "He had the go-go look about him every time he took the ice."

Torrey: "Gravity was on Hart's side. He was built like a fire plug and had good balance. It was clear that he loved being an Islander."

Like the days when Gerry went down deep in the Hudson Bay Copper and Zinc Company mine, the defenseman quickly learned that expansion teams inevitably experience the NHL depths.

Hart: "It was a challenge at the start because we were short on talent; no question about that. But the core guys had faith in Bill and that eventually he would build a winner. And it didn't take that long either.

"In our second year we had Denis Potvin, who we got from the draft and guys like Bobby Nystrom and eventually Trots and later Bossy. They'd turn us into a team to be feared."

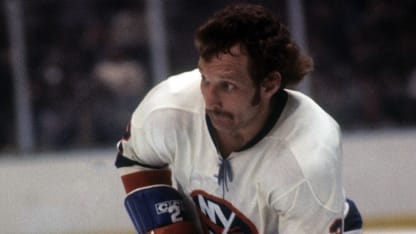

© Melchior DiGiacomo/Getty Images

As the team reached the playoffs for the first time in the spring of 1975, Hart had earned a league-wide reputation as a smart, solid, lunch pail-type player.

Historian Andrew Podnieks, writing in his book, "Players," described hard-working Hart in these words: "He was as unglamorous a defenseman as Denis Potvin was smiles and spotlight.

"He scored as few goals as Mike Bossy scored many. But Gerry rarely missed a game and went into the corners to fish the puck out with the same enthusiasm night after night."

Meanwhile, Hart's improvement became evident via the arithmetic. During the 1974-75 season -- the club's first playoff year -- Hart finished with a plus-minus mark of plus-28. A year later he was plus-35 and then plus-30.

"The downer for Gerry," said Devellano, "was that he missed our first Cup year by one season."

Like Westfall, who retired after the 1978-79 campaign, Hart wasn't around for Bobby Nystrom's 1980 Cup-winner. Gerry had been claimed by Quebec after the 1978-79 run and finished his career in St. Louis.

Serious knee and clavicle injuries forced him into retirement at 33. But by that time he had come to love the Nassau and Suffolk scene, determined to make it his home.

Gerry would return to The Island and launch business ventures. One was a glamorous ice palace in Hauppauge called The Rinx.

Sure, it was a long way from Flin Flon, but Gerry never forgot his past. After all, it was what made him what he was to become in Uniondale -- a proud, original Islander!