Shirley Walton Fischler would have been proud.

Watching Shannon Hogan and A.J. Mleczko dissecting an Islanders game on MSG Networks, would have pleased Shirley to no end.

My late wife then would have delivered one of her queenly kudos, "They know the score!"

No doubt, she'd have submitted a similar verbal salute to other women who've won acclaim in the hockey universe. The likes of Jessica Berman, Cammi Granato, and Kathryn Tappen were Shirley's kind of pros.

Maven's Memories: Shirley Fischler Breaks Gender Barriers in Hockey

The story of how hockey writer and author Shirley Fischler blazed a trail for women in hockey media

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

Likewise, she would have been thrilled to celebrate this month of March, honoring other women in hockey, who also know "The Score."

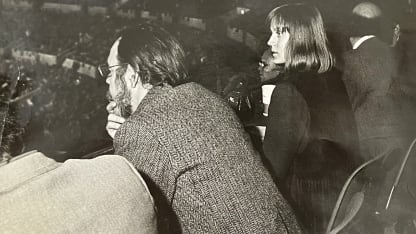

Trouble was, when it came to Shirley the score was 9-0 against her. She was being shut out of her profession.

Worse, she didn't even have a power play; or any kind of power for that matter. Shirley figuratively was ramming her typewriter against a male gender barrier and it wouldn't give. Not an inch.

"All I wanted to do was my job," she later would explain to the New York City Human Rights Commission, "And the guys wouldn't let me."

The "guys," to which she referred, included members of the all-male New York Hockey Writers' Association as well as the New York Rangers hierarchy. Collectively, they wouldn't let her do her job as a writer.

All Shirley wanted to do was cover a Rangers-Leafs playoff game for a legitimate daily newspaper which assigned her the gig. But she was adamantly refused that opportunity.

In the early 1970s, women -- no matter how well they knew their hockey -- were verboten in The Garden press box.

Matter of fact that discriminatory fact of life was enunciated in print on every single press ticket issued the Rangers. It spelled out, "Ladies not permitted in the press box."

When she read those six little words, en route to MSG's journalistic trenches, Toots -- that was her nickname -- turned to me and snapped, "What! Are they kidding?"

I shook my head. "You'll soon find out!"

And so she did.

Upon reaching the press area she was greeted by a guard; the keeper of the segregated sanctum, who simply stated, "Lady, you're not allowed in here."

To which she shot back her deathless question, "Are you kidding me?"

The protector of the pew shook his head in a manner indicating that neither Carrie Nation, Susan B. Anthony nor Eleanor Roosevelt would have been admitted -- because they were females.

Shirley had every reason to feel bewitched, bothered and, oh, yes bewildered. She already had paid her journalistic dues in many ways and at many venues.

By then, she had hosted a one-hour radio program, "Young Side," on the ABC network. She had co-edited Action Sports Hockey Magazine and had written a monthly hockey column, "Shirley On Shinny."

She never bragged about it but she worked side by side at ABC with the legendary Howard Cosell. "I tried to get him to like hockey," Shirley once lamented to me, "But he wouldn't listen."

In between raising a family, Shirley co-authored hockey books and was writing assorted features for the Toronto Daily Star, then Canada's most popular journal.

"I'm from Montreal and I know what good hockey-writing is all about," noted Bob Stampleman, publisher of Action Sports Hockey. "Shirley knows her hockey as well as any male writer I know. She writes with the best of them."

Then, a pause: "And she's darn good at Table Hockey, too. I've lost to her a few times."

Shirley was in no mood to be a loser in her Battle of the Press Box.

On the night she was forbidden from doing her job, she had been assigned to cover the Rangers playoff by the Kingston (Ontario) Whig-Standard, one of Canada's foremost and oldest dailies.

"For me it was a job," Shirley recalled, "And I was being paid good money to write about the series. You bet I was angry, You bet I was going to do something about it."

She did the following in short order: 1. She found an empty seat in MSG's Alpine reaches, put the typewriter on her lap and her notes under her seat and watched the game.

2. At game's end, she wrote her story and rushed it over to the Western Union office on Seventh and 40th. It appeared in print the following day.

And, 3. Early the next morning she hustled over to the Human Rights Commission. After spelling out her tale, she was granted a hearing.

She was well-prepared; armed with all the facts. To wit:

* REFUSED BY THE MALES: "I applied for associate membership in the NHL Writers' Association and was told that women could not belong to the Association because that would give me access to the press box. The men didn't want that to happen."

* PHONY ANTI-WOMEN ALIBIS: "One of their excuses for rejecting me was 'The dressing room,' Guess what? I didn't want to be in the sweaty, liniment-smelling dressing room. Then they said I'd be 'offended' by press box language. Ha! I could curse any one of them under a table!"

* KEEN RESEARCH: "I read the Association's fine print and found the secret words -- 'an organization for men.'"

But the men were dead serious about maintaining the ban. The Association quickly changed the word "men" to "persons." It also deleted "Associate" members, which was Shirley's qualification for the group.

What stunned me -- not to mention my wife -- was the fact that these male hockey reporters from The Associated Press, Newsday and the Newark News, among others, had been our good friends.

I co-wrote Rod Gilbert's autobiography with one of them and yet he was testily at the forefront, leading the anti-Shirley battle. Only one writer, Neil Offen, of The Post wrote a column defending Shirley's right to write.

Shirley: "I was called a 'crybaby,' a 'trouble-maker,' and a 'publicity hound' just to name a few of the mildest expletives. The names didn't hurt me; but being banned from doing my legitimate job did. So I fought them all."

Eleanor Holmes Norton of the Human Rights group orchestrated the hearing which MSG augmented with its top attorney. Shirley won the case and saved the signatures. One was from MSG's rep, John C. Diller, and the other from the Commission's Joy Meyers.

There was no celebration. Shirley was diffident about the victory; militantly against any publicity. "All I wanted," she said, "was the right for any woman to cover a hockey game on equal terms with the men. No more, no less."

The fallout was fierce. All former friendships with fellow writers had gone up in the smoke of the sexist battle. Unpleasantly, she now had to face the faces that frowned on her.

"I had to be confronted by the male writers who had called me names -- or worse, trying to ignore me for two years," she remembered. "I still had to prove I was the pro I said I was."

That she did in many ways. In 1973, she became the first woman hired as a tv analyst by a Boston station for Whalers WHA games. Teaming with The Maven, she was half of the first husband-and-wife tv tandem.

She co-authored the first definitive Macmillan "Hockey Encyclopedia," a mammoth editing task if ever there was one. All this while guiding her two boys, Ben and Simon, through childhood.

An empowering evening of reflection & motivation!

— New York Islanders (@NYIslanders) March 19, 2021

The #Isles Women in Sports panel series is happening on March 31st.

The 1st of 3 panels features:

🔹 @HC_Women's @Nursey16 🏒

🔸 @USWNT's @SammyMewy ⚽️

🔹 @USASwimming's @KathleenBaker2 🥇

Sign up now: https://t.co/LiYkgk8MCT pic.twitter.com/XTlw0AgDVG

Of her early, foes, Rangers GM Emile 'The Cat' Francis eventually changed his tune and made her feel warm and welcomed. Other enemies remained on the other side of propriety.

"As I walked past some of the male writers during 'The Cat's' press conference," Shirley chuckled, "One of the guys leaned to another and whispered loudly, 'Who's that, one of the player's wives?'"

Nonplussed, she continued to forge ahead of the field. In fact, she beat all the males to become the last journalist to interview Hall of Fame goalie Terry Sawchuk before he died.

Her story was an exclusive in The Toronto Daily Star and drew raves across the continent.

Shirley also helped ghost John Ferguson's book, "Thunder and Lightning," as well as Maurice 'Rocket' Richard's autobiography, "The Flying Frenchmen." She interviewed the Rocket at dinner in Montreal.

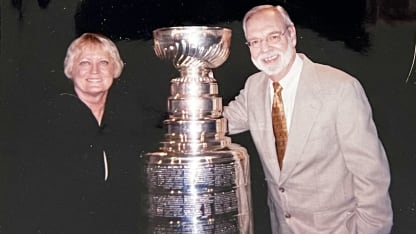

Not that it mattered much but she wound up writing more hockey books than any of the writers who had banned her from membership,

Never, but never, did she seek any form of recognition for her works. She just loved covering hockey.

"Some of my most fun," she once recalled to me, "Was just being with hockey people because they're real people. I mean being able to interview players like Gordie Howe and a goalie like Les Binkley was priceless for me.

"Nothing could beat the Summer dinners we had with Lou Lamoriello; especially when I tried to tell him how to run his team. Lou laughed at that one. I kind of think Lou enjoyed our banter as much as I did."

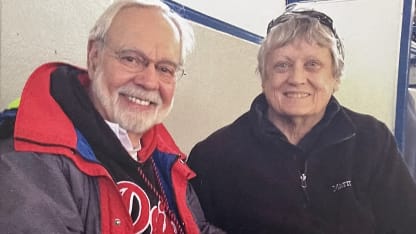

I suspect that the Islanders President and GM would agree. Without any fuss for fanfare, Lou showed up at the Memorial Service held for a few days after Shirley's passing six years ago.

"I had the opportunity of reading a lot of Shirley's materials in my earlier years with the Devils," Lamoriello said. "Then, because of Stan being associated with the Devils, I had the pleasure of being in both Shirley and Stan's company on many occasions, to the point where we would have several dinners during the summer. Because of those interactions, I came to respect her knowledge and her personality."

Until now, nothing has been done to recognize Shirley's many contributions to The Game. In fact, many successful women in today's hockey business have never even heard about her.

Isles Girls Hockey Webinar Pt. 1

In a sense, she has been treated like a heroine without portfolio, except her portfolio is filled with firsts. There's no question that her quiet crusading has paved the way for the Shannon's and A.J.'s of today.

"Every female writer and broadcaster owes a debt of gratitude to a woman whose name they might not even know. Why don't they know it? Because as much as Shirley was a force to be reckoned with she operated mostly behind the scenes," author and hockey reporter Debbie Elicksen said. "As more and more women trickled into the reporting ranks, and ultimately the executive suites, Shirley opened that door and made sure it stayed open."

When my son, Simon, reviews his mother's accomplishments, he does so with a mixture of pride and wonderment.

"My mother never wanted the spotlight on her," Simon said. "That was one of her traits. It simply was about getting her job done, not about her feeding her ego.

"She knew and was aware that her actions could affect the future of all women in the hockey business," Simon continued. "She knew that if she tried to make a big deal about her predicament and embarrassed those she was trying to work with, it could end right then and there."

Simon speaks firsthand. He was attending Islanders games before he finished kindergarten. He watched and learned from his mom.

"When my mother broke barriers and brought the glass ceilings crashing down," Simon concluded, "She did so in a manner that protected the future of everyone who would be coming after her.

"I couldn't be more proud of Toots for being such a strong and selfless person. For sure, had she been able to watch Shannon and A.J. in action she'd have been darn proud of them!"