“I started buying them in packs, like with a stick of gum for 25 cents,” he said. “And soon I had garbage bags full of them. I used to build castles and forts in the living room with all the hockey cards. You didn’t think about the value back then. We’d be running jumping on the cards. Knocking down the castle.”

By the time his family moved back to Winnipeg when he was 12, the late 1980s, and early 1990s “Junk Wax” era of cards had exploded with multiple manufacturers in all sports.

“You’d just be buying boxes of cards,” Briere said. “I get the whole Pro-Set, then Upper Deck had just come out. And O-Pee-Chee, then Parkhurst and Topps. So, you’re just collecting everything. And then it became that I just wanted goalies. So, I started collecting binders and binders of those. And as I became a better goalie and started playing in juniors, I even collected OHL cards and college hockey cards.

“And then it became the just goalies I was playing with or against. Or, guys I played with or against who were playing in the NHL. Guys like Jamie McLennan, Danny Lorenz, and Mike Torchia. I just started collecting the cards of guys that I knew so there was some meaning behind it.”

Briere regrets selling his Roy rookie card for $195 for “gas money in college” but has managed to hold on to the first-year cards of Martin Brodeur, Dominic Hasek, Clint Malarchuk, and Bill Ranford. He’s got goalie cards from the early 1970s of Gilles Meloche, Gerry Desjardins, Phil Myre, and Roy Edwards and some later vintage of Hall of Famer Tony Esposito while his oldest are position players from the early 1960s — Hall of Famer Dickie Moore and Doug Mohns.

Ultimately, Briere’s goal in collecting wasn’t to make money, only memories. His self-proclaimed “coolest” card is a 1992-93 Roy “mini card” from Kraft Singles pre-autographed from the goalie’s Colorado Avalanche days. And he derives value in other ways off the countless binders of cards now filling large Tupperware storage tubs back home in Minnesota.

For one thing, he loves that the cards depict the changes in modern goalie equipment. He’ll spend hours sifting through his stash to see how things have evolved into what Kraken goalies Joey Daccord and Phillip Grubauer wear today.

“It’s mostly things like that – seeing the equipment they wore back then,” he said. “I’ll be like ‘Oh, I remember that glove’ and ‘I had that glove’ or ‘I had that stick and I remember how bad that stick was.’

“You remember going to a glove with a ‘cheater’ from one with no cheater,” Briere said of modern catching gloves with a connected cuff and mid-section that provide an additional puck-blocking area. “I played with Ken Wregget and he played 20 years after the cheater was invented and you look at his cards and he still had a glove with no cheater.”

His cards also depict how “blockers went from just the glove and a pad to the finger paddings on the inside.” Briere will also look at his cards to study the evolution of goalie masks and how past netminders rarely wore cages.

“When I was a kid, if you wore a (Chris) Osgood mask, it meant you’d made it to juniors and oh wow, then you were cool,” he said, referencing the former Detroit Red Wings goalie from their champion 1990s years who wore distinctive headgear known as “The Helmet” – a regular hockey helmet and cat’s eye cage combination.

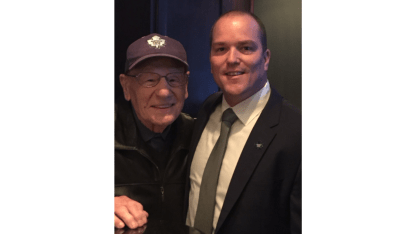

But largely, Briere derives his biggest satisfaction from the goalies behind the equipment. Especially when he gets to meet them. His favorite hockey memory came when he was coaching in Toronto and former Maple Leafs Hall of Fame goalie Johnny Bower phoned him up at home and asked whether they could watch a game together. So, they spent three hours in Briere’s box at a Leafs home game analyzing the netminders.