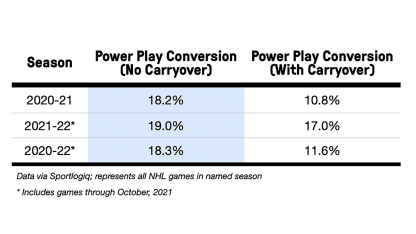

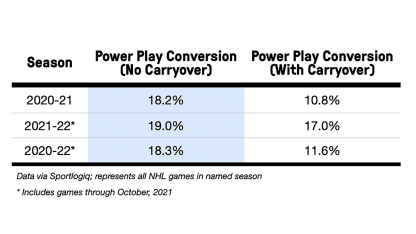

We see that over the past two seasons, a power play that is contained within one period is more successful than one that is broken across two. The more games we included in our evaluation, the more we find this to be true.

Why might this be? Well, Brown (who played on the penalty kill) has his theories. Sure, a team can watch plays on the bench and talk with coaches and teammates in the game about adjustments, but intermissions give time for focused planning and video review with no distraction - and without the need for a timeout to draw up a play upon returning. But maybe that helps a penalty kill unit more than a power play group.

"Coaches can go in and say 'all right, they've done this on the power play twice already so they can see it on video when you go into the locker room... The coach can pull players aside and say, 'they've been really looking for that slap pass in the middle, let's try to make sure we have our sticks the right way, or they're looking for this play, so how are we going to try to adjust.'

"I think that's something that can be put into consideration because if the power play is working... and is getting good looks and just hasn't scored, you're going to keep trying for those same looks because they were working. You're not going to think 'we need to change our power play because it's the start of the period,' because what you've done so far works."

Additionally, in Brown's opinion, it's harder to change a power play in game (unless you practiced different formations) as compared to a penalty kill.

There are still more questions that come up, of course. One of them was already front of mind for Brown: and that's how much do these conversion rates change depending on how much time is spent on the power play before an intermission versus after.

Other things to explore:

Future work can continue to uncover new data - and hopefully answers - on this specific point, but perhaps the biggest takeaway is we always want to marry what our eyes see and what data measures when we do any analysis.

"Whatever the stat or the play, you name it, the eye test is there and when you (also use data) you get that full picture, not just one side," Brown said. "Here, we can back up (our opinion) or it could have gone the complete other way because we just didn't know, or we weren't watching the right games when something happened.

"It's really cool that we can blend the hockey world, statistics and analytics, and just bring everything together to find one answer. We figured something out here that I wouldn't have been able to do by myself... When you have the numbers, the numbers will tell you exactly what was there to see and if you were right or wrong, and even if I was wrong, I learned something."