And his father helped. He’d come of age in Minnesota when legendary 1980 “Miracle on Ice” gold medal Team USA coach Herb Brooks from the Winter Olympics in Lake Placid was honing skills behind local college benches.

Like Brooks, Bjorkstrand’s father is renowned in Denmark for his intense, disciplined nature, with meticulous attention to detail at playing with and without the puck. And his son, tied for second in Kraken team scoring with 26 points this season, has largely emulated that.

Bjorkstrand on Thursday faces the Columbus Blue Jackets squad he spent his first seven NHL seasons with, mostly under demanding head coach John Tortorella – who’d actually played a year alongside Bjorkstrand’s father at the University of Maine starting in 1980.

“He was a really good player,” Tortorella, who coached the Blue Jackets for six seasons starting in 2015-16, once told local Columbus media members early on of Bjorkstrand’s dad. “Really skilled. It just makes you feel so old when you reconnect and stuff like that and now, I’m coaching his son.”

Tortorella added: “With Oliver, he skates on top of the ice. Todd was the same way. Todd was cerebral, he was a finesse guy back in those days at the university.”

Bjorkstrand said living up to his father’s demanding work ethic and attention to detail likely prepared him for life under Tortorella better than most.

“They’re both hard coaches but in a bit of a different way,” Bjorkstrand said. “Torts is probably, honestly, a little more intense. But my dad’s pretty demanding. He expects hard work and so on.”

Bjorkstrand feels his father, now coaching a pro team in Slovakia, has softened his approach slightly from years ago to be more in-tune with modern players. But he “hasn’t changed his principles” about hard work and getting the details right – such as clearing pucks out of your own end.

“You’ve got to learn that and you can’t be all pouty about it,” Bjorkstrand said. “So, yeah, I think for me, it prepared me for having a coach like Torts.”

And for the demands and styles of any other coach. When Kraken coach Dan Bylsma made Bjorkstrand a healthy scratch for a November game – sending a message to the Kraken that nobody was beyond reproach – the team’s lone All-Star from last season appeared to take it in stride and immediately scored a go-ahead goal against Vegas upon his return.

“End of the day it just comes back to working hard and the right way,” Bjorkstrand told the media afterward.

The nonplussed reaction didn’t surprise the father who first coached him professionally. Once, while coaching Denmark’s entry at the IIHF World Junior Hockey Championships in December 2011, Bjorkstrand’s dad suspended five of his players for a game after they were filmed fooling around on a media podium following a 10-2 loss to Canada. The teens were devastated and Bjorkstrand’s father received some public criticism for being overly harsh but wanted to send a team-wide message about “the wrong way to act” after a blowout defeat.

Of his son’s Kraken sit-down this season, he said: “He’s just got to take it and learn from it and try to be better. You just have to listen to your coach and try to do the best you can.”

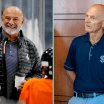

Todd Bjorkstrand, now 62, was only 26 and still harboring distant NHL dreams when former longtime Blue Fox captain and then-coach Frits Nielsen phoned him out of the blue asking him to play in Denmark. He knew nothing about the country and had just scored 67 goals in two seasons for Indianapolis and Fort Wayne in the minor pro International Hockey League. But the NHL also had relatively few Americans back then and he was at the age where prospects cross into has-been territory.

“I figured I’d just go over, play a season, and then move on to a higher league,” the elder Bjorkstrand said of going to Herning. “But then I signed one more year and met Oliver’s mom.”

And thus, he remained in Herning for years to come with his now former wife, Janne, and their sons, Oliver and his older brother Patrick. Bjorkstrand’s father won seven championships in 14 seasons as a Blue Fox player, six more as the team’s coach, and his retired No. 22 – the same number his son wears for the Kraken – was hung from the Herning arena’s rafters.

More importantly, Bjorkstrand’s record-setting on-ice success brought with it an intensity previously unseen in Danish hockey. Frits Nielsen, the coach who’d brought him there, describes it as “a will to win unlike anything I’d ever seen before.”

Denmark wasn’t exactly a hockey nation. The country’s first and only native NHL player had been Poul Popiel, who debuted with Boston in 1966 and had never even tried hockey before moving to Canada at age 8.

After being destroyed 47-0 by Canada in its first international foray at the 1949 IIHF World Hockey Championships, it would take Denmark another half-century to advance beyond lower-level play. Into this culture of near-invisibility in a soccer-mad nation walked Todd Bjorkstrand, who winced at seeing some Blue Fox players smoking in the dressing room, or day-drinking after practice.

So, he did something about it.

If teammates were too lackadaisical in on-ice workouts, Todd Bjorkstrand shot frosty glares their way. When some appeared hungover, he’d fire rocket passes that ricocheted off their sticks.

Eventually, with Bjorkstrand’s dad filling the net with goals as well as changing the culture, the Blue Fox began winning big. And as more foreign import slots were made available, others were lured to Herning. Among them, Finnish-born former Vancouver Canucks forward Petri Skriko and a onetime Canadian junior hockey tough-guy defenseman named Dan Jensen, who teamed with Bjorkstrand’s dad for a string of Herning championships behind the goaltending of a local named Ernst Andersen.

At the tail-end of his playing career in 1999-2000, Todd Bjorkstrand got a 16-year-old teammate – Frans Nielsen, son of the coach who’d brought him to Herning a decade earlier. Nielsen would go on to play pro in Sweden and then the New York Islanders starting in 2007 – the second native Dane to make the NHL since Popiel in 1966 and the nation’s first homegrown player.

“I played on a line with him, and you were squeezing your stick,” Nielsen said of Bjorkstrand’s father. “Because if you made a mistake, he was on you. I’ve never seen a guy who wanted to win like him.”

Nielsen, 40, played 925 NHL games for the Islanders and Detroit and last week was named to the International Ice Hockey Federation Hall of Fame for his pioneering feats. He now works as an international consultant for the Kraken and said Oliver Bjorkstrand shows many of the same traits his father long preached.

“He plays the right way,” Nielsen said. “There’s no cheating. He’s not the biggest and strongest guy but he comes out of the corners with those pucks. He’s got some high-end skill, but what makes him good is the way he competes and works.”

Bjorkstrand’s father maintained the same disciplined mindset and will to win when transitioning directly from player to Blue Fox coach in 2002. Despite his prior college teaming with Tortorella – who he described as “a great guy to be around” – he said he was already intense on his own and his coaching style is influenced more by Team USA legend Brooks than the current Philadelphia Flyers’ bench boss.

Among his first players was Peter Regin, who spent three seasons with the Blue Fox ahead of playing pro in Sweden and later 243 NHL games with mostly the Ottawa Senators. Regin has cited Bjorkstrand’s father as the most influential coach of his career.

Another player Bjorkstrand’s dad coached was the son of his former Canadian tough guy teammate Dan Jensen. Nicklas Jensen had been born and raised in Herning and after a season with the Blue Fox at age 16, played major junior hockey in Canada ahead of a 31-game NHL career with Vancouver and the New York Rangers.

And Todd Bjorkstrand’s former Blue Fox goalie teammate Ernst Andersen would later send his Herning-raised teenage son, Frederik, to play a season under him. He’s now with the Carolina Hurricanes, recovering from knee surgery, and his next NHL game will be the 500th of his career.

Oliver Bjorkstrand was the fifth of the Herning Five to make the NHL, having modeled his career path largely after what he’d seen Nicklas Jensen do. Just a few years younger and good friends with Jensen’s brother, Bjorkstrand joined the Blue Fox at age 16, then moved overseas a year later to play junior hockey for the Portland Winterhawks.