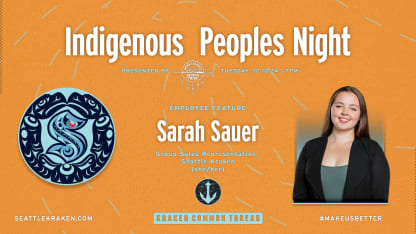

You know when you know. For Sarah Sauer, high school days featured a wealth of knowing.

It started with the Kraken group sales representative becoming “a lot more intrigued” about her personal connection to the culture and history of the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa tribe in northeastern Minnesota, Sauer’s heritage on her father’s side of the family tree. In middle school, living in Port Orchard, she attended a weekly Native American storytelling session as part of a diversity program presented by the school district. She could bring a couple of friends, making it more inclusive, and it sparked her curiosity. As a freshman at South Kitsap High, she was determined to “get serious.”

“At the age of six, my great grandpa was taken to a Native boarding school, Carlisle Indian Industrial School,” said Sauer. “He successfully ran away on his third attempt [at age 14].”

Boarding schools in the U.S. in the late 1890s were started to assimilate Native Americans into the Western economy – many historians would add to simultaneously teach a white, Christian culture. Research by Denise Lajimodiere, a retired North Dakota State University professor and member of the Turtle Mountain band of Chippewa Indians, showed most students were trained to be menial laborers. In her book, “Stringing Rosaries: The History, The Unforgivable and the Healing of Northern Plains American Indian Boarding School Survivor,” Lajimodiere further uncovered many schools were rife with sexual abuse, violent methods of discipline and poor medical care and living conditions. The book is based on interviews with 16 former “survivors” who, as children, were forcibly taken from their homes to attend boarding schools.

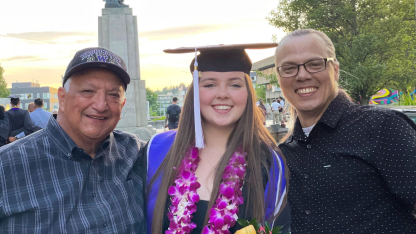

Sauer’s great-grandfather found his way to New York (“he used to pay five cents to watch the Yankees through a hole in the fence, sparking four generations of avid sports fans including the Kraken staffer) When he became an adult and was no longer a boarding school target, the elder moved back to the Bois Forte Indian Reservation, where he met Sauer’s great-grandmother. The couple moved to Washington state in 1944 to shield their son, George Brown, Sauer’s paternal grandfather, from any potential boarding school interaction.

“It's really sad, they [great-grandparents] saw friends perish,” said Sauer, Kraken colleague who is always upbeat through the rigors of group night details across a 41-game home schedule (including Tuesday’s Indigenous Peoples Night) but clearly capable of recognizing the horrors faced by past generations. “Because of the boarding school, they never wanted their children [George Brown was one of seven siblings] to learn the language. Both to protect their children and due to the segregation of people of color in the 1940s and ‘50s. They didn’t want their kids to have another mark from society.

“They still maintained aspects of the Native culture and traditions but did not pass down the language. At the time my grandpa was born, boarding schools were still a reality in the Midwest. They wanted to get far away from.”

Reversing the Missed Generations

Sauer said when grandpa George Brown’s first son, her dad, Mathew Brown, was born, the family decided it was time to fully and openly reintroduce the Bois Forte Band naming ceremony: “It was really important for my grandpa and my dad to hold on to that culture. So with us [Sauer and her siblings], we were the first in generations to go through the official naming ceremony of our tribe and get indigenous names.”

George and Mathew Brown teamed up to hold the naming ceremony here in the Seattle area for granddaughter/daughter Sarah when she was a year old. A bunch of cousins and an uncle, plus several great uncles, traveled from northern Minnesota to attend. She received her Bois Forte Band name, Agongos, which translates to chipmunk, identified as “energetic and full of life.” OK, here to say, they got that right about Sauer.

The naming ceremony reopened the door to her heritage, later fueled by those middle school sessions. In high school, she made the extra effort to connect to her paternal family’s culture and history. Applying for colleges, she took advantage of her knowledge about Bois Forte Band while writing the mandatory college essays and considering whether schools offered Native American history courses.

Discovered Her Calling, Deep Roots

Sauer had an interest in sports medicine (she played basketball and tennis, swam, dove, and ran cross-country for South Kitsap high school teams). The University of Washington offered those courses and, as Sauer points out, “what better place than UW” to study Native American history and culture.

The Native American academic deep-dive worked out, but Sauer soon discovered “biology and all wasn’t really my forte.”

“I was in the diversity program at UW,” said Sauer. “I went to its study hall all the time for math[tutoring]. An adviser said, ‘I think you'd be really good at business. I connected with an adviser at Foster [UW’s business school]. I realized there was a business side of sports that I could still do big time. I dove into that, went through the sales certification, and met a few people while I was doing a seasonal job for the Mariners.”