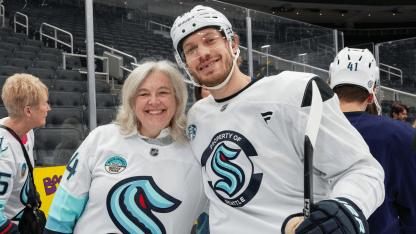

And she feels it’s something her children have all utilized in their fields, be they elite sports or other pursuits. She moved to Canada in her 20s, met her future husband, Richard, while visiting a friend on a Toronto movie set he was working on as a writer, and later had three children with him – Jamie, Penny and a middle sister, Hayley, who became a competitive figure skater in her teens and later a rower at Northeastern University.

Richard Oleksiak, a 6-foot-8 screenwriter from Buffalo, is in the sports Hall of Fame at that city’s powerhouse Nichols prep school – later playing rugby and lettering in track at Colgate University. He has two children from a prior marriage: Jake, who was recruited to play NCAA Division 1 hockey at Clarkson University before an injury, and Claire, a competitive skier.

All five Oleksiak siblings and half-siblings were close growing up and remain so, having traveled to Paris together with their parents last summer to watch Penny compete in her third Olympics.

Oleksiak’s mother said she and her husband encouraged them to play multiple sports, as well as pursue other hobbies. Music was required learning: Jamie became proficient in the trombone as a youngster but now leans more towards guitar while also learning to play piano.

Her father, Eric, was behind pushing that as well; still playing the clarinet, accordion and violin today at age 89.

“My father today will still talk to Jamie about his career post-hockey,” Alison Oleksiak said. “Because he’s concerned about his well-being and that he has something to do after hockey ends.”

She said her dad recognized the importance of life beyond sports even while first introducing her to swimming back in Troon.

“I think it gives you confidence,” she said. “I think it particularly helped give me confidence. It helps you learn to work within a team dynamic where it’s important to have a common goal. And I think that’s what I found.

“And the other thing is, I think it helps break barriers,” she added. “Because I think that for a lot of people, you can talk about dreaming but you’ve got to believe it. And I think when you’re in sports you kind of learn the roller coaster road. Sometimes you’re going to fail and sometimes you’re going to succeed. And so understanding those balances in life is important for folks.”

As a young female swimmer, she’d also felt the “barriers” broken in that gender domain sent the right message as well.

“I think it’s important in terms of a diversity perspective,” she said. “In terms of people seeing women and seeing diversity in sports. To understand that there are opportunities. My dad was really big on all that.”

To hear Kraken defenseman Oleksiak tell it, so was his mother. Oleksiak said she and his dad always seemed more concerned about how sports were a means to an end rather than an end goal of any sort.

“They were bigger on academics more than athletics,” he said. “I mean, they knew it was natural to be a Canadian kid and playing hockey. But they were always on me to use that to get into college and get an education. Obviously, I took a little detour from that but I’m sticking with it.”

Oleksiak played only one season for Northeastern University before switching to the Ontario Hockey League for a year and turning pro right after that. But he’s now taking additional college level courses through an NHL Players Association program, which is something his mother – who’d wanted him to stay in the NCAA – is very happy about.

“Her job is super complicated,” Oleksiak said of his mother. “All I know is, she’s always on conference calls and she’s using a lot of complicated acronyms that I don’t understand.”

Oleksiak also isn’t too clear about his mother’s athletic accomplishments, though he knows there were several.

“She doesn’t really speak much about it,” he said. “I don’t really think she wants people to know. But I’m curious to learn more. So, yeah, if you find out anything it'll be something I didn’t know.”

What is clear is his mom was a nationally prominent age level swimmer in Scotland, which competes internationally under a Great Britain umbrella. Alison Oleksiak was emphatic that she never represented Britain at any international events – usually a pre-requisite for making an Olympic team -- so speculation over whether she could have gone to a Games someday is arguably moot.

By the time she was 11 in October 1976, she’d competed at the Scottish age group championships in Edinburgh – placing first in the 100-meter backstroke and fourth in the 100-meter freestyle. As a 13-year-old at the Club Championship of Great Britain regional heat in November 1978, she placed second in the 200-meter individual medley event open to all ages.

She’d been peaking as a 14-year-old a year ahead of the 1980 Olympics, but details from there are sketchy. Britain’s Olympic committee made a controversial decision to not join other Western nations in the Moscow Games boycott, followed by tremendous pressure from the British government and public at-large on athletes to stay home.

Some did and some didn’t.