There isn’t much that new Kraken center and free agent pickup Chandler Stephenson remembers from growing up in Saskatchewan that didn’t involve a big brother two years his senior.

He’d tag along with his brother, Colton, to the nearby outdoor rink in their Saskatoon hometown, shoot pucks with him day and night against plywood-padded walls in the family’s basement, or wreak havoc on a backyard trampoline seeing which sibling could bounce the highest or do the most backflips. They were “best friends” who never fought but competed intensely against one another at everything, to where Stephenson once inadvertently got some teeth knocked out in one basement matchup but quickly excelled at hockey against players his own age.

“You’re just kind of thrown into it because the older kids, they’re older, bigger, stronger and all that,” said Stephenson, 30, who took the ice this week at Kraken Training Camp, pres. by Starbucks fresh off leaving the Vegas Golden Knights and signing a seven-year, $43.75 million contract.

“So, he had friends that he’d go play with and I’d join in with them,” he said, adding: “I just think when you have an older sibling, and you kind of see how it’s done visually rather than being told, it just wound up being better for myself.”

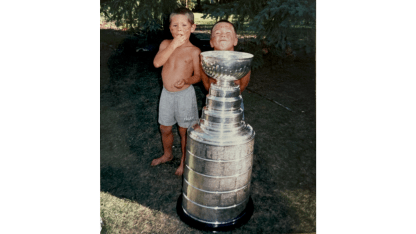

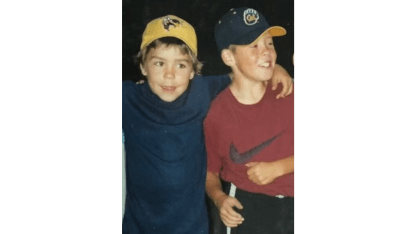

One of those older pals he began hanging with, around age 10 or 12, was from a town two hours away and his brother’s teammate on a Saskatoon-based summer hockey all-star squad. He’d been staying weekends at the Stephenson family home to avoid travel back-and-forth to his hometown and it soon became a trio of the brothers and older friend denting the basement walls with pucks, bike riding to the neighborhood park and bouncing on the trampoline.

The friend? Present-day Kraken winger Jaden Schwartz.

“We played in tournaments and traveled a lot, so when I was in Saskatoon I’d stay with their family sometimes and Chandler was always around,” said Schwartz, who’d become well aware of both brothers over the years even before living with them; all three having competed against and grown to respect one another as star players on their respective squads.

“I got to know their family very well,” Schwartz said. “I was good buddies with Colton and then as Chandler got older, we always kept in touch. I was always rooting for him a little bit because when you play with somebody as a kid and then you grow up, it’s always fun to see him do well. I’ve known Chandler since I was probably 8 or 10.”

And Schwartz isn’t surprised that Stephenson, who first donned skates at age 3 to emulate the hockey-playing brother he idolized, became as dominant as he did so quickly.

“When you’re a young kid and you’re with older guys, I think it pushes you a little bit to where you want to keep up with the older kids,” Schwartz said. “And I think it makes you better. I did that as a young guy when my brother was two years older. So, it was probably similar with Chandler wanting to play with his brother and his older friends.”

When Stephenson was considering multiple offers in July from various teams, Schwartz was phoning and texting him. Schwartz even sent Stephenson photos of a local golf course he played at, knowing it was the next favorite sport of his good pal’s kid brother.

The Kraken in camp are expected to explore that early-life chemistry even further by deploying Schwartz and Stephenson on the same forward line, a trio that could also include Andre Burakovsky. Back in 2018, Burakovsky and Stephenson were young forwards on a Washington Capitals team that won the Stanley Cup along with present-day Kraken goalie Philipp Grubauer.

Stephenson, a 6-foot, 209-pound two-way centerman, makes the Kraken instantly more competitive in the middle of the ice, on special teams and on faceoffs. He also brings a fierce competitiveness borne of that backyard competitiveness with his brother and some veteran experience to a Kraken center position already loaded with young talent in Matty Beniers, Shane Wright and eventually – the team hopes – this summer’s No. 8 overall draft pick Berkly Catton.

And having Schwartz around has made the team and city switchover more comfortable for Stephenson, his wife, Tasha, a daughter, Nellie, born in April and a young toddler son, Ford.

“It’s kind of come full circle,” he said with a chuckle.

Stephenson figures he was about 7 or 8 when first meeting Schwartz on-ice and doesn’t see much difference in the “familiar face” that makes him harken back to times with his brother at the house.

“Back then, he was funny, and he’s still funny,” he said of Schwartz. “He’s really genuine. And just the same from what I can remember. We were very young, but he still seems the same to me.”

Ultimately, he said, his Kraken decision came down to “family” and picking a region with good schools, a strong support network and other attractions befitting their planned long-haul stay. The importance of family to Stephenson isn’t surprising, given the close bond with his brother. And the fact he’d met Schwartz because his parents, Bev and Curt, frequently opened their home to players and friends, whether for backyard cookouts or simply a place to crash.

Stephenson was from a hockey family: His cousin, Joey Kocur, was a notable Detroit Red Wings tough guy who won a pair of Stanley Cups in 1997 and 1998 and another with Kraken Hockey Network broadcaster Eddie Olczyk on the 1994 New York Rangers. An uncle, Bob Stephenson, played a handful of NHL games for Toronto and Hartford in 1979-80, while two other cousins, Logan and Shay Stephenson, played professionally in Europe and Asia.