As I walked up Channelside Drive, dodging the trolley as I crossed over Water Street, I wondered what morning skate would look like, or if there'd even be a morning skate. That question was answered soon after arriving at my desk by a League memo advising teams not to skate. There would be a Board of Governors call at 1 p.m. to decide the fate of the season.

Our content team was also holding a meeting at 10 a.m. I was hesitant to attend. I had just gotten back from the last road trip with the team a day earlier, a three-city, five-day jaunt through Boston, Detroit and Toronto. The night before, someone on Twitter checked the Jazz schedule against the Lightning and saw Tampa Bay twice played in the same arena as Utah a day later. The Jazz played in Boston Friday night; the Bolts beat the Bruins at TD Garden Saturday. Utah faced the Detroit Pistons on Saturday; the Lightning were in Detroit Sunday to take on the Red Wings. Three days later, Gobert's coronavirus test came back positive, igniting the mass of lockdowns and cancellations that swept the country.

In Boston, the Lightning shared the visitors locker room at TD Garden with the Jazz less than 12 hours after Gobert had left it when accounting for Tampa Bay's morning skate at TD Garden early Saturday.

I was unsure about confining myself in an office with co-workers who weren't on that road trip, possibly infecting them if I had picked up the virus while traveling. The meeting was optional. I skipped it.

A couple hours later, the NHL announced the season was being paused.

There would be no game that night against the Philadelphia Flyers.

There would be no games period for an indefinite amount of time.

I gathered up my gear, grabbed what I would need to work from home and walked out of the arena early Thursday afternoon on March 12.

I hadn't been back since.

Until now.

---

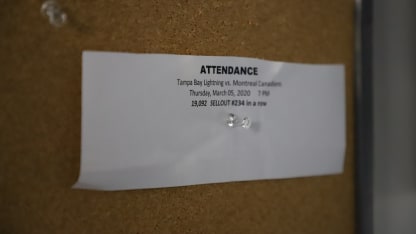

I heard the arena had an eerie, empty feel to it now, nobody roaming the corridors, everything still set up in anticipation for that game against Philadelphia.

So I decided to check it out, to see the reminders from that day two months earlier when everything changed.

When I enter the arena through Security - Gate D, I'm greeted by Susan Danielik.

Danielik is the Lightning's director of premium and guest services.

Today, she's scanning the forehead of anybody who enters the arena with a no-touch thermometer, making sure those who are feverish don't enter. Danielik's one of a handful of full-time Lightning employees taking a shift at the arena to give security an extra hand. Today was the first time she'd used the new thermometer.

"We're learning," she said, smiling.

I pass, got a 97.4.

I can enter.

The lights are shut off in the bowl. Only the green glow from the exit signs at the top of the stairs of every section and a few rays peeking out from behind the curtain separating the concourse from the rink keep it from being pitch black.

There's hardly anybody in the arena. During the hour I walk around, I run into two people outside of the security command. At one point on the concourse, I thought I heard a group of people up ahead, just out of sight. When I rounded the bend, nobody was there. The voices belonged to Fleetwood Mac, which was playing from the speakers inside the bathrooms.

A light flickers at the DEX Imaging sponsorship space in one of the concourse corner areas.

Behind a replica Lightning bench, a LED screen shows a repeating loop of Lightning fans celebrating.