Mere blocks from Capital One Arena, one can find the National Archives Museum, home to the Bill of Rights, the Constitution and The Declaration of Independence, as well as other important and iconic documents and artifacts. Also in that building, in the Lawrence F. O’Brien Gallery, and through Jan. 7, 2024, one can visit an exhibit entitled: “All American: The Power of Sports.”

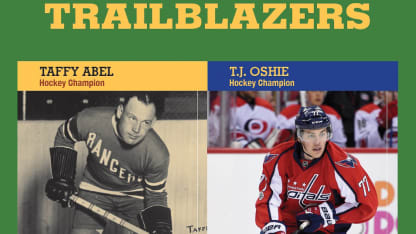

The “All American” sports exhibit includes a panel titled, “Trailblazers,” and two hockey players are pictured – Clarence “Taffy” Abel on the left, and T.J. Oshie on the right. Virtually everyone in these parts knows T.J. Oshie, but who is Clarence “Taffy” Abel, and what makes him and Oshie trailblazers?

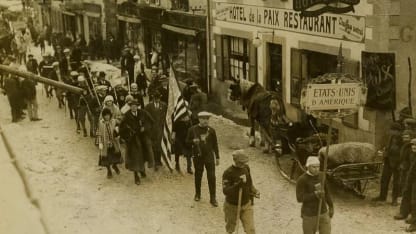

Quite simply, Abel was the first Indigenous American to play in the NHL, and the first Indigenous American to participate in the Winter Olympic Games. Abel was a member of the 1924 U.S. Olympic team in Men’s Ice Hockey, and he was chosen as Team USA’s flagbearer for those 1924 Games, held in Chamonix, France, the very first Winter Olympics.

“They’ve made a pretty decent display there,” says George Jones, Abel’s nephew. “In terms of the three Native Americans who have represented the U.S. [in men’s hockey] at the Winter Olympics, Taffy Abel was the first one in 1924, Henry Boucha was the second one in 1972, and T.J. Oshie was the third one in 2014.

“And they were all Ojibwe, though different tribes. To me, that says something right there. I know the Native American spirit that my uncle had, and he was a fierce competitor. People would ask him what business he was in, and he would say, ‘Well, I’m in the business of winning.’”

That same fierce competitive spirit was always visible in the on-ice play of both Boucha and Oshie as well. Boucha, who passed away earlier this year, was Oshie’s uncle.

Abel truly was a trailblazer, but few were aware of it or knew of his achievements during his lifetime, and even fewer were aware of it during the course of his eight-year NHL career, which included two Stanley Cup championships, one with the New York Rangers and one with Chicago. During his playing career, only his closest family members were aware of his heritage. To his employers, his teammates and the fans, he was Taffy Abel, a big (6-foot-1, 225 pounds), bruising defenseman known for his body checks and his competitive nature. No one asked about his heritage; everyone assumed he was a white man from Michigan.

Abel was born on May 28, 1900 in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, just over the bridge from Canada in Michigan’s upper peninsula. Initially, Abel’s family opted to keep their heritage a secret, worried that exposing their Indigenous heritage might result in Clarence and his sister being removed from the family unit and sent away to a boarding school for Native American children.

It’s estimated that as many as 150,000 Indigenous American children were forcibly taken from their families and placed in boarding schools where they were discouraged and/or prevented from speaking their native language and practicing their traditions and tribal and cultural rituals. Even worse, those children were subject to some horrific conditions at those schools, and some of them died there.

“It was like living in two different worlds,” says Jones. “If you're a Native American, you know some of that way of life, and I know he did, because we would always talk about it. After he passed away, my aunt would talk about it. His mother didn’t want it to come out until after she passed away, but the thing is, unless his mother and father protected him and his sister by saying, ‘Hey, they're not native. They're white,’ he would have probably been taken away in, like 1905 to a Native American boarding school in Mt. Pleasant, Mich.

“Among family and friends, we always knew he was Native American. We had no problem with it. But from a professional standpoint, and from a protective standpoint, back in 1905, if I was his parent, I’d have done the same damn thing.”

Clarence came by his nickname because of his love for the candy as a kid. He grew up playing hockey like many kids in that part of the world, and he attended the local public schools. When his father passed away in 1920, Abel took whatever jobs he could get to support his mother and his sister. But he also kept playing hockey at an amateur level.

“He was playing for St. Paul in 1923 when he got discovered to go to the Olympics,” says Jones. “He played for both St. Paul and Minneapolis. Any city of any size up there had an indoor hockey arena.”

Ahead of the 1924 Olympic Games, Abel was recruited to represent the U.S. team. The official who recruited him had earlier tried to have Abel banned from the sport for life because of “ruffianism,” but that same official also recognized his value to the U.S. Olympic team. But Abel had no money for the equipment or the travel.

“Taffy did not come out of wealth,” says Jones. “He didn’t have the money to go to the Olympics, then finally, someone loaned it to him. Then he met a representative for the A.G. Spalding Company, and they donated the jerseys, and the ice skates, and the clothes. And I know some of the other people – the families from Sault Ste. Marie – that put the money together to get him there.”

Abel and Team USA won a silver medal at the Chamonix Games, and the captains of the other U.S. teams chose him to be the flagbearer for the traditional procession before the start of the Olympic Games.