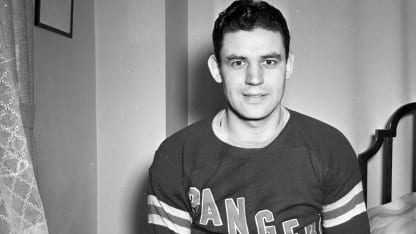

Pratt mixed skill, wit on road to Hockey Hall of Fame

Defenseman kept teammates laughing, helped Rangers, Maple Leafs win Stanley Cup

If any Hockey Hall of Famer could pull off such a challenging double dip, it would be Walter "Babe" Pratt. His antics and one-liners had teammates laughing while he was helping his teams -- the New York Rangers and Toronto Maple Leafs -- to Stanley Cup championships. Pratt won the Hart Trophy as the NHL's most valuable player in 1944, and he was considered one of the best offensive defensemen in hockey history until Bobby Orr arrived in the NHL in 1966, the same year Pratt was inducted into the Hall.

Of course, as Pratt admitted during an interview in 1968 when he was an executive with a lumber company in New Westminster, British Columbia, "I did it my way," rather than that of his bosses, Lester Patrick in New York and Hap Day in Toronto.

Pratt was the leading scorer in every league played in, from midget to junior, before joining the Rangers in 1936. But as part of New York's Stanley Cup-winning team in 1940, Babe sacrificed his individual scoring numbers to fit in with what captain Art Coulter called "The Rangers Machine."

In fact, whenever Pratt rushed the puck over the blue line and tried to score on his own, his teammates would playfully rib him, saying, "For crying out loud, stay back and don't be messing up our forward lines!"

C. Michael Hiam, author of "Eddie Shore and that Old-Time Hockey," described Pratt as having a "freight-handler's body and Girl Scout's face."

That face almost got him a role in an MGM movie called "The Great Canadian," starring Clark Gable as a hockey hero. The studio wanted Rangers center Phil Watson to double for Gable and Pratt to be the villain.

Eric Whitehead, author of "The Patricks: Hockey's Royal Family," remembered Babe's reaction.

"As far as the doubles were concerned, Pratt thought it was pretty bad casting, and he was so upset he went to [general] manager Lester Patrick's office to protest. 'Lester,' he said, 'can you imagine Phil Watson as Clark Gable? Why, he's not only ugly, he can't even speak good pidgin English!'

"'Babe,' Lester replied soothingly. 'Can't you see that Gable wouldn't dare risk having a handsome young man like you acting as his double? My goodness, Babe, haven't you ever heard of job insecurity?'"

Pratt agreed that maybe his boss was on to something and reluctantly agreed to go along. When it came to job insecurity, Pratt never had a worry; it wasn't part of his DNA.

In his book, "Players: The Ultimate A-Z Guide of Everyone Who Has Ever Played in the NHL," Andrew Podnieks described Pratt in these terms:

"At 6-3 Pratt was the tallest man in the NHL. He was also good-looking, young, energetic and most definitely a man about town. As they said, he knew the emergency exit to every hotel in New York. He had Hollywood looks and the braggadocio of (legendary boxer) Jack Johnson."

There was a time in Pratt's career when parents may have questioned the influence of Pratt as a role model. In fact, Patrick dubbed his defenseman, "Puck's Bad Boy."

Patrick wasn't alone in that assessment. Rangers coach Frank Boucher described some of Pratt's falls in his book "When The Rangers Were Young."

"Babe didn't hit hard," recounted Boucher, "but he had an unusual knack of sticking out his rear end, sort of sideways, and tipping the attacking player off his feet.

"I remember once in the playoffs -- Babe and his teammates were getting no breaks whatsoever from King Clancy, who became a top referee when he retired as a player. There were two men in the penalty box and Babe was backtracking quickly after ragging the puck and then losing it. He collided with Clancy, inadvertently or otherwise, and knocked King from his feet. As Clancy scrambled quickly up, he snapped ominously at Babe, 'I'd like to be playin' against you tonight, Pratt.' Babe looked toward his teammates in the penalty box and then returned his glance.

"'Well,' Babe asked innocently, 'aren't you?'"

As for the defenseman's run-ins with Patrick, he insisted he was too easy a target for his employer, who seemed to have a Pratt radar machine in his pocket.

"It was like every time Lester walked into a room, especially during the playoffs, I wouldn't necessarily be drinking, but I would be there," Pratt said. "I always got caught. Somebody else could be drinking away in another hotel or pub, but Lester always managed to find me.

"I wasn't doing any harm, but Lester used to make it a lot worse than it was and I used to go along with it as a gag. One time, he said, 'I'm not going to fine you. I'm not going to trade you. I'm going to send you to the minors until you rot.'"

Pratt laughed because he was sure Lester would never go through with his threat. "He finally wound up fining me $1,000, a fantastic sum when you're making only $5,000 per year. He kept it for one month, but I was playing so well that he felt guilty and gave it back."

But in the end, each wanted to win more than anything. Pratt respected that.

"All that we players ever got from Lester was straight common sense," Pratt said. "He was a great theorist and believed in doing things the direct, simple way. After we'd win a game and had made mistakes doing it, he'd really get after us. But if we'd been badly beaten he'd lay off.

"He was a disciplinarian, but he left it to the players to police themselves. He'd say, 'As long as you play good hockey, I don't want to hear about any trouble.' There were times when we'd take advantage, but mostly it worked. We respected his attitude."

With the outbreak of World War II, the Rangers lost more manpower to the armed forces than any other NHL team. They needed bodies, so on Nov. 27, 1942, Patrick traded Pratt to the Maple Leafs for forwards Hank Goldup and Red Garrett. To Pratt's astonishment, he was paid more by the Maple Leafs than he ever received in New York. As a result, he began to play even better.

Toronto coach Hap Day also gave Pratt the green light to stickhandle when and where he pleased. He responded to his emancipation by winning the Hart Trophy in 1943-44, finishing with 58 points (17 goals, 41 assists) in a 50-game season.

Pratt readily admitted that Day was the "greatest coach in hockey," but said he didn't have too much fun when Hap was around. "He wasn't a very complimentary guy," Pratt said. "If you bumped into him in the street, he'd say, 'Nice pass you made in Chicago,' and that would mean that you gave the puck away."

But Day, himself a member of the Hall of Fame, appreciated Pratt most of all during the Stanley Cup Final in 1945, when Toronto won the first three games against the Detroit Red Wings before the Red Wings won the next three, sending the series to Game 7 at Olympia Stadium in Detroit.

Mel Hill gave Toronto a 1-0 lead at 5:38 of the first period, but Detroit's Murray Armstrong tied the game 1-1 at 8:16 of the third. Soon after, the Red Wings were penalized and Pratt was sent out on the power play. He took a pass from Nick Metz and beat goalie Harry Lumley at 12:14 to put Toronto ahead 2-1. Pratt and his teammates preserved the lead, and Toronto won the Stanley Cup for the second time in four years.

Typically, he revisited that night in a rather whimsical way.

"I'll always remember that Cup-winning game and my winning goal -- plus what happened before that," Pratt said. "Before the game started, Hap paced around the living room of our hotel suite we shared while I was snoring in bed.

"He came in and dumped me right out of bed and yelled, 'How the hell can you lay there and snore before the seventh game of the Stanley Cup Final?'"

As usual, Pratt had the last words and the perfect squelch:

"Well, the game doesn't start for another hour. There's no use in me doing any worrying until then."

Then, a pause: "That's your job!"