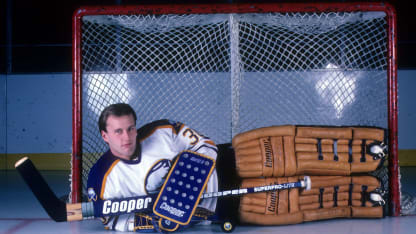

Mike Richter couldn't believe his luck. His coach at the Northwood School, where Richter was playing as a prep, had previously coached Tom Barrasso at Acton-Boxboro High School. The other goalie was, already, a legend, having jumped straight from high school to the NHL, taking the League by storm and winning the Calder Trophy voted as its top rookie, the Vezina Trophy as best goalie and finishing ninth for the Hart Trophy as most valuable player in 1983-84.

And now Richter got to sit down for dinner with Barrasso, in his second NHL season, and Tom Fleming, the coach and common link. Barrasso seemed impossibly old and worldly, even though only a single year separated the two goalies.

"He was just so mature and accomplished and experienced," said Richter, who played 14 NHL seasons and won the Stanley Cup with the 1993-94 New York Rangers. "When you're young like that, all you want is, 'How do you do it? What do I need to do? What changed? What was a hurdle?' And he was saying some things like, 'Well, you know, when guys are coming down, you know where they're going to shoot.'

"I'm thinking, 'Do I?'"

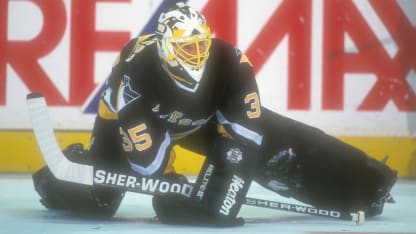

It was that ability to see the game, that sheer confidence, that helped Barrasso go on to the career he would have, one that will result with him going into the Hockey Hall of Fame.

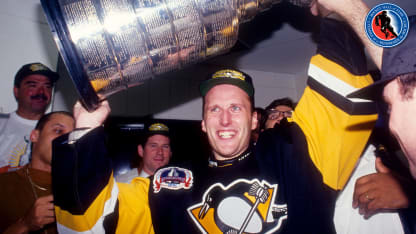

Barrasso finished his 19-season NHL career 369-227-18 with 86 ties, a 3.24 goals-against average and .892 save percentage in 777 games for the Pittsburgh Penguins, Buffalo Sabres, Ottawa Senators, Carolina Hurricanes, Toronto Maple Leafs and St. Louis Blues from 1983-03, and played for the 1991 and '92 Stanley Cup champion Penguins.

His was a career that would hit impossibly high highs, like the rookie year unlikely to be replicated and the Stanley Cup wins, and impossibly low lows, like the cancer fight his daughter Ashley went through, which combined with the death of his father caused him to take off the entire 2000-01 season.

But it all started with that brilliant first season, one that introduced him to the NHL with a lightning bolt.