Legendary hockey reporter Stan Fischler writes a weekly scrapbook for NHL.com. Fischler, known as "The Hockey Maven," shares his humor and insight with readers each Wednesday.

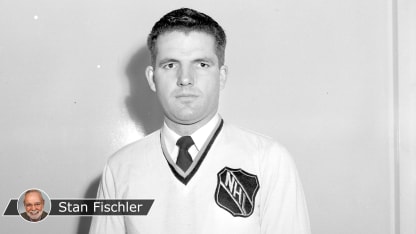

This week Fischler features his popular segment, "Voices From The Past," with Hall of Fame referee Bill Chadwick. Known as "The Big Whistle," Chadwick revealed in several interviews with Fischler how a serious eye injury ended his hockey playing career and that, in turn, led to him becoming a respected NHL referee.

Chadwick officiated 811 regular-season games and 107 Stanley Cup Playoff games over 16 NHL seasons. He then moved into the broadcast booth as an analyst for the New York Rangers. Chadwick was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1964 and died in 2009 at the age of 94.

This oral history originally was recorded over several sessions in the late 1960s and through the 1970s. Many of the following passages originally appeared in Fischler's books, "Those Were The Days" and "Metro Ice."

Chadwick was NHL referee, Hall of Famer despite losing sight in eye

Impairment 'made me work harder' to gain respect, legendary on-ice official said

How did you manage to become a hockey player in New York City?

"I was different. I grew up in the 1930s when there weren't many rinks around. But my father bought me a pair of racing skates when I was 10 years old; and when Central Park Lake froze over we'd go there and sometimes to the Brooklyn Ice Palace which was one of the few indoor rinks. The Ice Palace was special because it allowed -- unlike some other places -- the long-bladed racing skates to be used. Then, I heard that my school, Jamaica High School, had a hockey team so I showed up for tryouts. But since I couldn't use racing skates, I borrowed hockey blades and made the team."

How did you progress as a player?

"Since I was so keen on getting to the top, I played for as many teams as possible. In addition to playing for my high school team which won the city championship, I found other clubs. One was the Floral Park Maroons, a good amateur team and another was the Stock Exchange Brokers which played in the Metropolitan League. In those days Met League games were played on Sunday afternoons at (old) Madison Square Garden. We Met Leaguers would play at 1:30 and after our game the New York Rangers' farm team, the Rovers, played an Eastern League game at 3:30. I was so enthused about hockey I also skated for the Jamaica Hawks and Fordham University. For Jamaica, I played under the name of O'Donoghue and with Fordham, I used the name Flanagan."

How involved were you with the NHL and playing more hockey?

"I became a Rangers fan and used to sit up high in the gallery rooting for Bill and Bun Cook, hoping that, maybe, someday, I might make it to the NHL. But then a couple of accidents changed my career. I was 19 years old and playing in an all-star game. As I stepped on the ice a flying puck hit me smack in the right eye. I was hospitalized and, finally, doctors said there was no way of restoring sight in that eye. That was tough but I came back the next fall and continued playing but with only one good eye. Believe it or not, I got good enough to play for the Rovers which was just a step or two away from making the Rangers."

What went happened next?

"I did well enough with the Rovers in 1936 and was back with them a year later. During one of our games, I got hit either with a stick or a puck in my good eye, the left one, and my vision was gone. Fortunately, it cleared up and I was able to see out of the eye again. But this time I decided it wasn't a good idea to take a chance on playing again so I retired as a player while still wanting to be part of hockey, 'cause I loved the game so much."

How did you make the transition from playing to officiating?

"I can thank Tommy Lockhart for that. He ran the Eastern Amateur Hockey League and one Sunday I was at the Garden about to watch a Rovers game. There was a blizzard outside and Lockhart told me that the regular ref couldn't make it and would I pinch hit? I was glad to and did a good enough job that he had me do Met League games. Then I was an Eastern League linesman and finally a referee. Next, I got a call from NHL President Frank Calder asking me to be a big-league linesman and, finally, a referee."

But you only had one good eye; how did that affect your officiating?

"I had a psychological advantage and was a better official. Because I was using only one eye that fact always was on my mind. It made me work harder than the other fellows. I skated harder and was closer to the play. In most cases I was on top of it. Besides, everybody on the Board of Governors -- the NHL owners -- knew I only had one eye and never said anything about it; except for two guys."

Who was that and what happened?

"It was the seventh game of the 1945 [Stanley] Cup Final between Toronto [Maple Leafs] and Detroit [Red Wings]. It was the third period and the score was tied when Syd Howe of the Red Wings crosschecked the Leafs Gus Bodnar. With Howe in the penalty box Babe Pratt of the Leafs scored the winning goal and Toronto got the Cup. That infuriated the Wings manager Jack Adams and the owner Jim Norris. They protested to the League and as a result of their noise every year after that I had to go for an eye exam at the start of every season. But that wasn't the toughest part of the job."

What was the toughest part of your job?

"Intimidation; or at least attempts at it. In those days, we referees were not allowed to lock our dressing room doors. After every period somebody would come in and complain, trying to intimidate. As a result, they would wait in line outside just to get in and intimidate us. Meanwhile, I was going along, doing my best. My condition didn't hamper me. I had 20-20 vision in my good left eye. I never was away from the net when there was a play on goal and I didn't have much trouble from the players; just a few."

Which players gave you a hard time?

"Maurice Richard of the [Montreal] Canadiens and Ted Lindsay of the Red Wings. They gave me the toughest time although I never thought they were just picking on me. I believe it was part of their personal makeup and their character. They would have done it to anybody. In Richard's case, he was the fiercest competitor I had ever seen in any sport. If you weren't playing on the same team as Maurice you were his enemy. That also applied to referees giving him penalties."

Did the fact that you had only one good eye ever get you into real trouble?

"During World War II I received a draft notice. I asked for a two-week deferment so that I could clear up the playoffs before going into the Army. Somehow, that wound up in a Detroit newspaper and there was a headline, ONE EYED REFEREE ASKS FOR DRAFT DEFERMENT. Fortunately for me, nobody else picked up the story; not even the New York papers. As it turned out I wasn't drafted and continued refereeing."

In your day the referee had to break up fights; how tough was that?

"I had one rough time of it in the 1947 Final between Toronto and Montreal. In one of the early games Rocket Richard cut Vic Lynn of Toronto and I gave Richard a five-minute major. Later in the game Richard got into a fight with Bill Ezinicki so I went in between them. But Richard reached over my shoulder and cut Ezinicki in the middle of the head. That meant a 20-minute match penalty and that Montreal had to play shorthanded for 20 minutes. Toronto won that game and League president Clarence Campbell suspended Richard for the next game. The Leafs went on to win The Cup."

Sinbin mayhem: Howie Meeker and Tony Leswick are in the penalty box. Referee Bill Chadwick, Linesman George Hayes and Linesman Butch Keeling on January 3, 1948 at Maple Leaf Gardens, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The Toronto Maple Leafs and the New York Rangers tied 5 - 5.

What was the craziest incident you encountered?

"Detroit had a tough defenseman Jimmy Orlando, who came from Montreal. On this night I'm working Red Wings-Canadiens at The Forum when a fight broke out in the stands and Orlando's father was involved. So, Jimmy climbs over the boards and starts up the steps in the stands with skates, stick and all -- and the rest of his team follows him before I could stop them. The only guy I could get to was Eddie Wares, who was running up there with stick in hand. I yelled, 'Eddie, drop your stick.' He dropped it all right but somebody hit him right on top of the head with a bottle and cut him wide open. In the end I was sorry I told him to drop his stick. To make matters worse I had to ride down to New York that night on the same bus as the Red Wings. It was murder."

What was your secret for good officiating?

"Common sense. Another trick was to gain the regard of the older players on each team -- the leaders. It couldn't be done in a year or two; it took four, five years and more. I think I got away with more on the ice than any of my colleagues because I had the players' esteem. I could make a call that a new ref, who didn't have the players' respect, couldn't get away with, without getting the business."

When did you decide to quit officiating?

"In 1955 I had reached the ripe old age of 39 and decided to call it quits. It wasn't because I felt that I was losing it but rather I was at the top of my game and felt that I should leave while I still was on top. I had been officiating for 16 years in the NHL, had handled the biggest games. I believe I was capable of five more years but, in retrospect, it all worked out well."

You wound up as a broadcaster. How did that compare to officiating?

"I enjoyed the game more behind the mic than when I refereed. Sometimes I'd find myself in a rooting capacity and really liked that. Sometimes I even found myself yelling at the referees. Frankly, I wasn't very proud of it. But I've never called a referee 'a blind bat' because I knew I might only be half right saying it!"

Photo credit: Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame