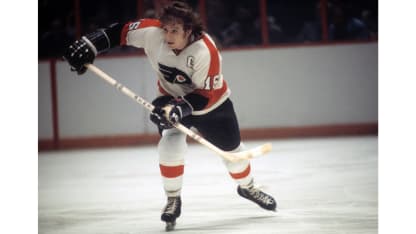

Just as prominent as the Flyers' point totals were their penalty totals, and they rewrote the record book there as well. Clarke was not only the Flyers' offensive and defensive catalyst, he often initiated those frequent punch-ups.

"It happened like in a Western movie," Stephen Cole wrote in his book "Hockey Night Fever." "The Flyers would ride into town spoiling for a fight. Bobby was the guy on the lead horse, squinting into the sun, figuring out how to bust into the local Wells Fargo. The plan, always improvised, usually began with a calculated provocation -- a face-wash, a spear, a wild elbow. The other team retaliated, as expected. And then the Flyers bench emptied, alive with manufactured rage, justified in beating the hell out of smaller, more law-abiding teams. Afterwards, the Flyers galloped off, waving their hats in the air, two points safe in their saddlebags, heading off to the next town, another job down the line."

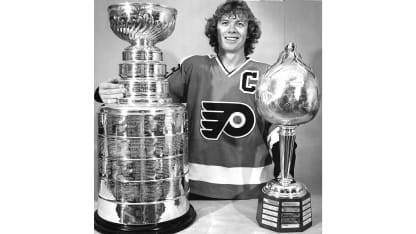

Clarke matched his assist record in 1975-76 and had an NHL career-high 119 points and a League best plus-83 rating. He earned his third Hart Trophy as the Flyers led the Campbell Conference with 118 points, the best showing in franchise history, and made a third consecutive trip to the Cup Final, though they were swept by Montreal.

Over the next eight seasons, Clarke remained a productive player. He received serious consideration for the Hart Trophy nearly every year and began drawing more attention for his defensive excellence, capturing the Selke Trophy as a 33-year-old in 1982-83, which was also his most prolific late-career season (85 points). Along with his 1987 induction to the Hall of Fame, winning the Selke was one of his most cherished honors.