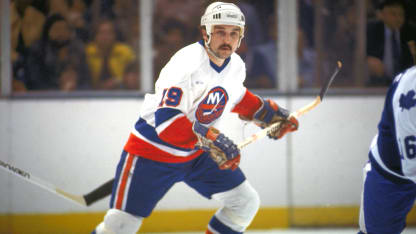

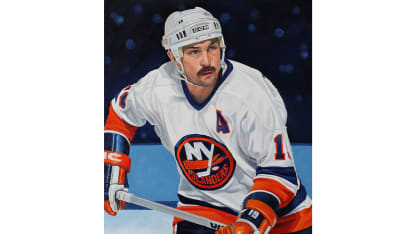

Trottier was on his way, and when Arbour paired him with Mike Bossy on one wing and Gillies on the other, he was at the center of the most dangerous line in the League. Trottier finished second in scoring to Guy Lafleur in 1977-78 with 123 points, and then moved up to first a year later, when he had 47 goals and 87 assists for 134 points and was a ludicrous plus-76 on his way to winning the Hart Trophy.

Still, Trottier never seemed impressed with his achievements, never carried himself as if he were a big star, embodying the lunch-pail ethos that was at the heart of the Islanders' dominance. He never forgot the Frenchman Creek days, nor the help he got from his teammate with the Swift Current Broncos, Dave "Tiger" Williams, who remains one of his closest friends. The NHL's all-time leader in penalty minutes (3,966), Williams may be known to the wider hockey world as the goon's goon, but Trottier -- universally known as "Trots" to his teammates -- knows another side of Williams, who didn't just befriend the 15-year-old Trottier, who was away from home for the first time. He protected him and taught him how to fight, the two of them sparring most every day after practice.

Indeed, it was Williams who might've rescued Trottier's career before it even started. Horribly homesick in his first year with Swift Current, Trottier was tired of getting roughed up and had come to almost hate hockey. He told his father, the dam-buster, that he wanted to quit and go back to school. Trottier's parents never pressured him, and Buzz Trottier told his son if he wanted to quit, he could, provided that he called the coach and told him.