McDonald played vital role in shaping Orr's career

Coach converted Hall of Famer from forward to defenseman, encouraged him to play creatively

A demolition derby on skates, McDonald played 11 NHL seasons from 1935-45 for the Toronto Maple Leafs, Detroit Red Wings and New York Rangers, winning championships with Detroit in 1936 and 1937 and Toronto in 1942.

He played in the longest game in NHL history, skating for Detroit in its 1-0 win in six overtimes that spanned two days (March 24-25, 1936), pocketing $185 in bonus money from a loyal Red Wings fan who paid him a princely $5 for each of the 37 Montreal Maroons he unofficially flattened.

After his playing career, McDonald would coach minor pro hockey in Rochester, New York, and Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. More than three decades since his death at the age of 79 on July 21, 1991, he remains a legend not just in hockey, but Canada's other national pastime: lacrosse. He was inducted into the sport's Hall of Fame in 1971.

McDonald was also prominent in federal politics, serving three terms as a member of Canadian Parliament in Ottawa for the riding of Parry Sound-Muskoka before retiring undefeated in 1957.

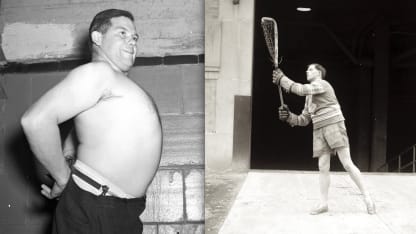

Bucko McDonald puffs out his chest during Toronto Maple Leafs training camp in 1942 (left). In an undated photo, he is wearing a Maple Leafs sweater while holding a lacrosse stick outside Maple Leaf Gardens (right). Imperial Oil-Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame

But Bucko, so nicknamed as a boy in his native Fergus, Ontario, for his rawboned ruggedness and athleticism, has a greater legacy than all of that. It was McDonald who coached Orr, then a young prodigy, for two seasons in Parry Sound, Ontario, converting the forward into a defenseman and encouraging him even as a teenager to play the game creatively and instinctively.

With this freedom moving forward, first with the major-junior Oshawa Generals and then the Boston Bruins, Orr would reinvent the position of defenseman, taking the brilliant, freewheeling style of Montreal Canadiens superstar Doug Harvey to another level.

"Bobby Orr had the greatest impact of any player to come along in my lifetime," Canadiens legend Jean Beliveau wrote in "My Life In Hockey," his 1994 autobiography. "He earned his place in hockey history by singlehandedly changing the game from the style played in my day to the one we see today. In my mind, there can be no greater legacy."

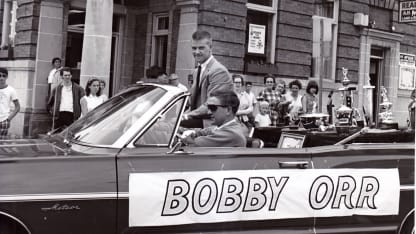

Bobby Orr, age 19, rides in a Canada Day parade in his hometown of Parry Sound, Ontario, on July 1, 1967, the country's 100th birthday, with his brother Ronnie behind the wheel. Le Studio du Hockey/Hockey Hall of Fame

Orr has spoken glowingly of the impact that McDonald had on his Hall-of-Fame career, both on and off the ice.

"Bucko McDonald was a giant of a man and quite a character, someone who always seemed to do things on his own terms," he wrote in "Orr: My Story," his 2013 autobiography. "He would often act as both coach and chauffeur for players if they couldn't get a ride to the rink for a practice or game.

"I'd hear Bucko's half-ton truck pull up to the house, where I'd be waiting patiently on the porch, and off we'd head to a favorite little truck stop, just outside of town on Highway 69.

"We'd land there before the game to have a nice pre-game meal, chowing down on all types of delicacies: hamburgers, french fries, ice cream sundaes and other essential food groups. Hardly what you might call a wise pre-game meal by today's standards, but Bucko never thought anything of it. He always said it didn't matter what you had in your stomach when you played as much as it mattered what you had in your heart."

Bobby Orr defends the Oshawa Generals net with goalie Dennis Gibson during an OHA Junior A game against the Toronto Marlboros at Maple Leaf Gardens on Jan. 20, 1964. Graphic Artists/Hockey Hall of Fame

Just as revolutionary was McDonald's system, or lack of it, when it came to a young player of limitless talent.

"Bucko allowed me to go with my first instinct on the ice: Never get rid of the puck when you can control it. Hold onto it and let the play open up in front of you," Orr wrote. "It was just a lot easier to make plays when you were in motion, and Bucko reinforced that concept in me.

"The best play in hockey is still the give-and-go, and you can't run that play unless at least one player is in motion. … I believe that Bucko and all of my other coaches helped my career by simply allowing me to go with my gut and skate with the puck."

McDonald would forever marvel at Orr's ability and his otherworldly vision, and Orr has forever credited his bantam and midget coach for the vital role he played, with his mentor being inducted into the Bobby Orr Hall of Fame in Parry Sound in 2015.

Watch: Youtube Video

Bucko was effusive in his praise during a visit to the Montreal Forum on March 21, 1966, having driven 200 miles to watch the Oshawa Generals' captain, who turned 18 the previous day, play against the Junior Canadiens. At the time, the Junior Canadiens were coached by Scotty Bowman, who commented that "nobody comes close" to Orr as a skater.

"He was an exceptional boy from the first time I saw him," McDonald said.

"He had all the necessary ability, was good with his stick and he was intelligent, a good scholar hockey-wise. I named him captain in bantam and midget and he was accepted as captain by the boys even though they were older. He was an idol to kids in Parry Sound. …

"He's a carbon-copy of Doug Harvey, and I consider Harvey the best ever. Bobby can skate faster and shoot harder than Harvey."

Then, prophetically: "Keep in mind that Bobby is only a junior, but the potential is there for him to be one of the greatest of all time. He could be an outstanding attraction in the NHL, the leader the Bruins have been looking for since Milt Schmidt retired (in 1954)."

Seven months later, Orr would debut with the Bruins, forever changing the game of hockey.

Bucko McDonald in portraits with the Toronto Maple Leafs and New York Rangers. Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame

In Orr's view, Bucko was "a great communicator," a skill his coach had learned while debating in Parliament and with hockey superiors with whom he butted heads more than once.

Physically, McDonald packed more than 200 pounds on his 5-foot-10 frame and was renowned as one of the heaviest hitters in the history of the League. He was built like a swollen rain barrel, a bottomless pit when he sat to eat.

"Bucko gets the power from hamburger sandwiches," hockey writer Dal MacDonald suggested of the Red Wings defenseman in a 1936 column. "Recently, he is reported to have consumed 15 of these at one sitting. When word of this got around, he was deluged by offers from Detroit restaurateurs to come and eat all he wanted, just to make a personal appearance."

Bucko McDonald, left, defends the Toronto Maple Leafs net with goalie Turk Broda against the Chicago Black Hawks during the 1938-39 season. Le Studio du Hockey/Hockey Hall of Fame

Still, Bucko's start in hockey came in a roundabout way.

He had been a brilliant lacrosse player, winning the Mann Cup with the Brampton Excelsiors in 1931 before passing on a spot on the 1932 Olympic team to join a team Conn Smythe operated out of Maple Leaf Gardens in the newly formed International Professional Lacrosse League. However, when the pro game collapsed later that year, making him ineligible to again play amateur, Smythe invited him to his NHL team's training camp in 1933 despite his skating leaving much to be desired.

McDonald would be assigned to the Buffalo Bisons of the International-American Hockey League, but warming the bench, he asked for his release.

Smythe replied with a telegram that said, "You're as washed up as January's thaw," and granted his wish, dealing him to the Red Wings on Jan. 2, 1935.

Bucko would go on to play five seasons with Detroit, including winning the Stanley Cup twice, before being traded back to Toronto in December 1938, evidently less washed up than Smythe had believed.

A third Stanley Cup championship followed in 1942, but in his final season with Toronto, Red Wings coach and general manager Jack Adams sneered at the stocky defenseman, responding to a few volleys McDonald had launched his way.

"McDonald? I seem to recall the name," Adams said sarcastically. "Isn't he that fat man who stood out there on the ice last night in front of (Toronto goalie) Turk Broda? I thought it was some fan who wanted a better look at the game. The fat fellow looked like a traffic cop, thumbing traffic in on the Toronto goal. He certainly wasn't stopping anything."

Shortly after, in November 1943, McDonald had his contract sold to New York, where he would play his final two NHL seasons.

Gordie Drillon (left) and Bucko McDonald (right) with coach Hap Day on Oct. 10, 1941, in Toronto's Maple Leaf Gardens dressing room on the eve of training camp.

Maple Leafs coach Hap Day referred to Bucko as "our second goaltender. He stops almost as many shots with his belly as Turk Broda does with his pads."

McDonald wore a thick leather pad under his sweater to give him more protection when he threw his considerable weight around. But teammate Billy Taylor had another idea.

"That's no ordinary belly protector," Taylor said. "Bucko protects himself with a huge plank steak inside his shirt. He nibbles on the meat on the bench. By the third period, he's wolfed it all down. That's why you seldom see him try to block a shot late in the game."

In total, McDonald played 446 NHL games, getting 123 points (35 goals, 88 assists) while adding another seven (six goals, one assist) in 50 postseason games.

Bobby Orr was two years old when Bucko played his final organized hockey in 1949-50, skating for the Sundridge Beavers of the North Bay (Ontario) District League while also serving in Parliament. But their paths would meet in Parry Sound in the early 1960s, McDonald by then scouting for the Red Wings.

"I wonder how many kids ever played under a coach who had been both an NHL player and a Member of Parliament?" Orr wondered in his book. "Once [McDonald's] team was put together, he was the kind of person who could see all the pieces of the big hockey puzzle, and he had that skill that all successful coaches have of putting everyone into their own special place within the bigger picture."

Months before Orr's NHL debut, McDonald was waxing poetic about a junior defenseman who today is in every discussion regarding the greatest hockey player of all time.

"Whenever he gets the puck, he becomes the focal point of everybody's eyes," McDonald said. "Very few players have that asset, just the Frank Mahovliches, Rocket Richards and Gordie Howes. Bobby is always in the right place at the right time, and because of it, the puck seems to come to him by radar. He just seems to have a sixth sense."