In 1948, the 8-year-old who was born Stanislav Gvoth left his home in Sokolce, Czechoslovakia. Father Juraj was a maintenance man in a textile factory. Mother Emilia raised vegetables to feed the family. They adored their son, so much that they agreed to send him to Canada, where he could have a better life.

Joe, Emilia's brother, and his wife lived there, having departed Czechoslovakia. They had no children, but they had freedom. Young Stanislav duly noted that, as well as amenities in their modest home: electricity, a refrigerator, space to spread out instead of sleeping four to a room.

"I really didn't understand Communism until I escaped from it," he said. "I vaguely remember German soldiers coming through our village in Czechoslovakia. Even after World War II ended, it was tough. But I still felt homesick in Canada. Whenever I saw a plane fly over, I figured it was the one to take me back to my parents."

STAN MIKITA CAREER TOTALS | View Full Stats

Games: 1,394 | Goals: 541 | Assists: 926 | Points: 1,467

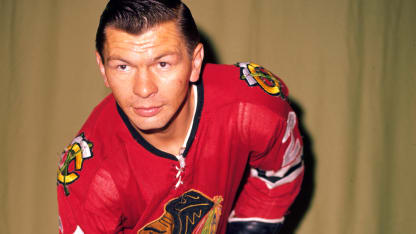

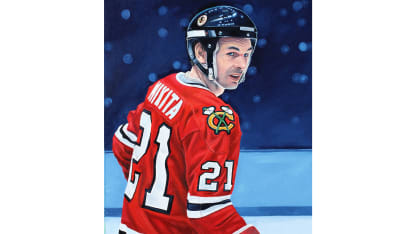

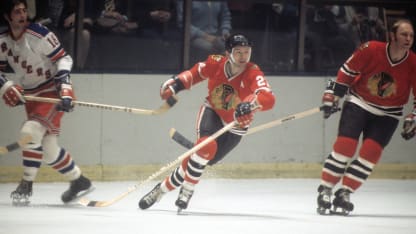

But his trip to Canada was not the short visit he thought it would be. He soon referred to Uncle Joe and Aunt Anna as his father and mother, and took their surname; Stanislav Gvoth became Stan Mikita. And as proof that truth is sometimes stranger than fiction, they resided in St. Catharines, Ontario, where a junior hockey team, the Teepees, would be sponsored by the Chicago Black Hawks.

The rest really is history. After a three-game taste of the NHL in 1958-59, Mikita emerged as one of the greatest centers in League annals over 22 seasons, all with Chicago. In 2011, he and fellow icon Bobby Hull were honored with statues outside the United Center. That was 31 years after Mikita retired, yet he still led Chicago in regular-season games played (1,394), playoff games (155), regular-season assists (926) and playoff assists (91). Mikita ranked second to Hull in regular-season goals (541) and third in playoff goals (59).