William Douglas has been writing The Color of Hockey blog for the past eight years. Douglas joined NHL.com in March 2019 and writes about people of color in the game. Today he profiles Harnarayan Singh, "Hockey Night in Canada: Punjabi Edition" play-by-play announcer.

Color of Hockey: Singh chronicles rise to fame in new book

'Hockey Night in Canada: Punjabi Edition' broadcaster went viral for Bonino goal call in 2016 Final

Harnarayan Singh wrote his first autobiography as a sixth-grade project while living in Brooks, Alberta.

"It's called, 'My Life,' and on the front it has No. 99 and it has that Easton aluminum (Wayne) Gretzky stick that I drew on it," Singh said of the book that sits on the memory wall of his home office. "It talks about me and my family, but there's also a paragraph that says, 'When I grow up, I want to be a hockey commentator.'"

Through determination and destiny, Singh's dream came true. He's the play-by-play voice for "Hockey Night in Canada: Punjabi Edition," and best known for his call of the winning goal by Pittsburgh Penguins forward Nick Bonino in Game 1 of the 2016 Stanley Cup Final against the San Jose Sharks that went viral.

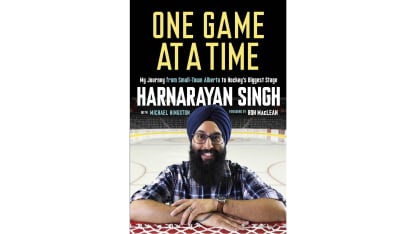

Singh chronicles his rise to become one of hockey's most recognized broadcasters in his latest autobiography, "One Game at a Time: My Journey from Small-Town Alberta to Hockey's Biggest Stage," which goes on sale Tuesday.

The book, written with Michael Hingston, shares Singh's love of hockey and his pride in his Sikh faith, and reveals the joy and pain that he and his family, who immigrated from India's Punjab region in the 1960s, experienced as the only Sikh family in a small western Canada town.

"It's been a while since I felt this excited about just everything career-wise, especially since I was able to incorporate my parents and their story of coming to Canada and bring in elements of my faith and my passion for Sikh music and incorporate all these hockey stories and my kids at the end," Singh said of the book. "I hope that it can also open doors for other mainstream books to be written by and about other diverse people."

Singh combines candor with humor in writing about the challenges he faced to accomplish what several people told him he couldn't: To become a prominent face in a predominantly white sport while speaking a foreign language, wearing a turban and having an ample beard that signifies his heritage and religion.

"The more difficult part [of writing the book] was when I talked about my experience as a child and some of the bullying I faced," Singh said. "That was actually surprising to my family. My sister, Gurdeep, who plays a big role in the book and in my life early on, she said, and my parents said, 'You never even told us. Reading the book is the first time we're hearing about this.'"

Singh said his passion for hockey, instilled by his older sisters who were huge fans of Gretzky and the Edmonton Oilers, helped him get through challenging times.

Hockey served as an ice-breaker, a conversation-starter and a badge to show those who questioned Singh's Canadian roots.

"I have so much to be thankful for for the hockey world because my experience growing up in Canada as a person of color, as a visible minority, would have been drastically different had it not been for hockey," said Singh, who was born in Wetaskiwin, Alberta, about 50 miles south of Edmonton. "I probably would not have made friends as easily, I wouldn't have had much of a rapport with my teachers, I wouldn't have had much fun growing up."

Singh received a mini-hockey stick as a gift from a cousin shortly after he was born. He used the stick as a toddler to imitate what players were doing on the ice. By age 4, he began imitating hockey broadcasters.

His parents bought him a yellow toy microphone and stand to perform his "broadcasts." By the time Singh was in the fourth grade, he had a cassette recorder and a keyboard in his room and was creating his own shows, complete with theme music.

"I was recording my own radio shows from the NHL awards to Sikh music awards," he said. "It was all about being a broadcaster."

In high school, a friend who was doing sports and news segments at a local radio station asked Singh to join him. A career was in the making.

"When they opened the door for me and allowed me to come on the air in Brooks, Alberta, then it put that light bulb and put that little seed of encouragement that if these guys are willing to give me a chance, maybe somebody else will too," he said.

Singh went on to study broadcasting at Mount Royal University in Calgary, earned an internship at TSN in Toronto and worked for CBC Radio in Calgary, all the while still dreaming of doing hockey play-by-play and encountering naysayers along the way.

When Singh told his family doctor what he wanted to do for a living, the physician briefly chatted with Santokh, Singh's father, then turned to Singh and offered some advice.

"He said, 'Look, boy, nobody looks like you on TV. The chance of you getting the role you want are so slim to none that you should be realistic and go for things that you can actually do to have a successful career,'" Singh said.

"Even when I was in Mount Royal University, some of the superiors, professors or teachers, had the same sort of mentality. Not all of them, and I don't hold anything against them either, but it was a cautionary tale to say that, 'You might have a better chance behind the scenes. What about producing?'"

In 2008, Singh got an unexpected call from Joel Darling, then an executive producer at CBC Sports. Darling told Singh that CBC was thinking about starting a Punjabi language broadcast and asked if he'd be interested in being part of it.

"Next thing I knew, I was sitting in Toronto at the CBC 'Hockey Night in Canada' headquarters, in a tiny booth next to (host) Parminder (Singh), calling the Stanley Cup Final," Harnarayan Singh writes in his book. "If it sounds like a blur, that's because it felt that way to me, too."

But in the whirlwind of reaching a lifelong dream, Singh had to overcome another huge hurdle: How to do the weekly broadcast from CBC's Toronto studio while living in Calgary.

With the show operating on a shoestring budget, Singh spent his own money on about 60 cross-country flights. He and Gurdeep plotted a rigorous schedule that had him on Friday red-eye flights to Toronto to prepare for the broadcast and back to Calgary on early morning flights on Sundays to arrive in time for temple service.

"I just couldn't give up the chance to be part of 'Hockey Night in Canada,'" he said. "It was such a dream and goal of mine, and it was right there. Those initial years, it's what I had to do to be a part of it. I don't have any regrets because I didn't tell anyone I was doing that because it would have been looked upon as being absurd and unreliable and I needed to prove myself to the show and show the commitment. The hope was that one day that would pay off, and thankfully it did."

Give an assist to Bonino. The Punjabi broadcast was doing well by 2016 in Canada, where six percent of the population is South Asian, nearly 456,000 of them Sikh, and Punjabi is Canada's fifth-most spoken language.

Randeep Sarai, a member of Canadian Parliament, said the Punjabi broadcast helps the growing South Asian population weave itself into the fabric of the country.

"What Hockey Night in Punjabi did is put everyone in the living room where kids, parents, grandparents could all sit and watch and they're learning the game as they go and they all get excited and they all get patriotic or nostalgic about their teams," said Sarai, who honored Singh and Oilers forward Jujhar Khaira in a House of Commons floor speech in March 2017. "It centralizes and unifies the family together to the Canadian experience. They all got to know what hockey's about, why it's so electric and why it's such an amazing sport."

But the social media response to Singh's enthusiastic call of Bonino's goal catapulted his popularity and that of "Hockey Night in Canada: Punjabi Edition" beyond Canada's borders.

The Penguins liked it so much that they invited Singh and the Punjabi broadcast crew to their Stanley Cup victory celebration in Pittsburgh to recreate the call before hundreds of thousands of fans.

"To have people like Mario Lemieux come up and say, 'You're a part of Pittsburgh Penguins history and part of the Penguins family now,' it's just so, so special," Singh said. "I honestly consider that whole thing such a blessing. I'm just so thankful and grateful for the whole experience. It's helped the entire Hockey Night in Canada Punjabi show, it's helped myself personally. Most hockey fans in Canada knew who we were, but to help get us attention in the States, that was huge."

Singh said he enjoys doing the Punjabi broadcast, but he still has another career goal to achieve.

"My dream is still English play-by-play, I'd love to do that," he said. "I've been very fortunate to come on the English side as a host and that's been a great experience as well. I want to be doing this for the rest of my life so I'm hoping I've planted the seed to make that happen."

Photos courtesy of Candice Ward