But he also said the welcome mat wasn't always rolled out by opposing players and fans.

Racist taunts and gestures occurred at road games. Wright remembers a particularly jarring episode in Oswego, New York, where the seating area behind the visiting bench had to be roped off. But that didn't stop some fans from chanting a racist and homophobic slur at Wright's players.

"You notice it, but try not to let it bother you, get you off your game," he said of the taunts and verbal abuse. "You have to let people be who they are and say, 'That's their problem, not my problem.' My problem is dealing with this team, getting them motivated to be competitive."

He said that when the team stopped at a restaurant on the road it wasn't unusual for the server to not to hand him the bill, assuming that he couldn't possibly be in charge of the traveling party.

"It certainly wasn't easy, particularly in Buffalo," he said. "I was there for 43 years and there are some places you just can't go to in Buffalo. The abuse I took at some places, being refused service. It was a difficult road to hoe."

Campus initially had its challenges as well. Wright recalled that some Black members of the university's basketball team didn't want him hired because he was involved in a predominately white sport.

"They wanted to know, 'What the (heck) can you be all about. Who do you identify with? You certainly can't be in our corner,' because I was a Black hockey player dealing in the white world I dealt with all my life," Wright said. "It took some time before they realized what I was all about and that I was OK."

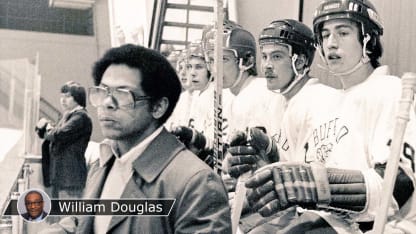

Wright cut an intimidating figure as a player and coach despite standing 5-foot-3 and weighing about 140 pounds. Several former players offered the same description of him: tough, demanding but fair.

"He was tough as nails and he would run our practice tough as nails," McGorry said. "Monday practice was always, 'Hey boys, gotta sweat them evils out.' Get all of the alcohol and food and everything that we consumed over the weekend, and it was going to get out of our systems on Monday."

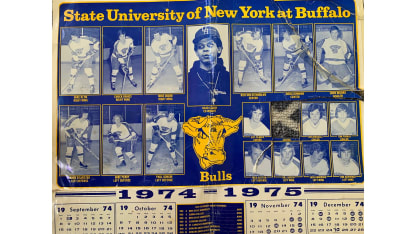

Mike Dixon, a former University at Buffalo forward, said Wright commanded the respect of other teams as evidenced by its schedule. Though it was a Division II school, Buffalo played many elite Division I schools.

"We had Clarkson University, St. Lawrence University, Western Michigan and Ohio State come to Buffalo to play us," Dixon said. "Those big schools, they didn't need us. I think coach Wright had everything to do with it. He made a great name for himself at BU, and I think that carried straight through when he started to become a coach."

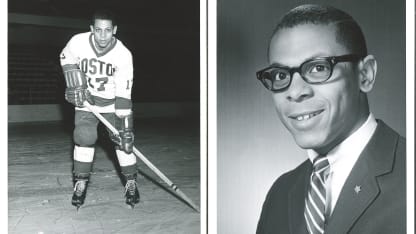

Wright was a fast, tenacious forward in college who scored 62 points (29 goals, 33 assists) in 65 NCAA games from 1966-69. He was part of Boston University's penalty-killing unit with fellow Chatham native and friend Herb Wakabayashi that once didn't allow an opposing shot on goal in 36 consecutive shorthanded minutes.

"He was nasty," said former Boston University player and assistant Jack Ferriera, now a senior adviser to Minnesota Wild general manager Bill Guerin. "He could skate like the wind and was always in the middle of everything. He didn't have a great scoring touch, but when he was on the ice you knew he was there."