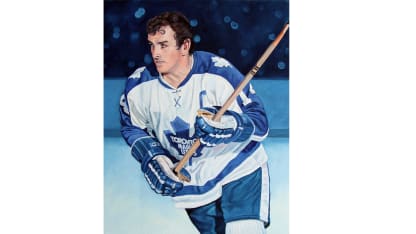

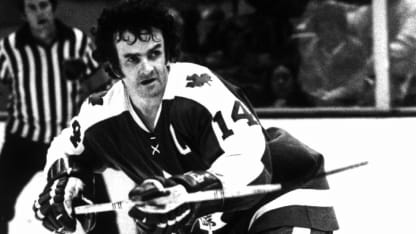

Keon's mother, Laura, was a teacher, and his father, David, worked for a mining company. He reflected the attributes of both parents; his mother's intellect showed up in his off-the-charts hockey IQ, and his father's discipline was evident in his steely resolve. "I loved how he would stick his jaw out," teammate and friend Bob Baun wrote in his autobiography. "You were never certain if he was mad or if it was a kind of determination you see in a dog that won't let go of a bone."

Keon played mostly on outdoor rinks until his mid-teens, displaying excellent skating and offensive skills. A Detroit Red Wings scout invited the 15-year-old to leave Noranda for a Junior B team, but his mother discouraged him from making the move. Then the Maple Leafs got interested and spent $1,000 to sponsor his Noranda youth team. One year later, in 1956, they invited him to join their affiliated hockey program at St. Michael's College, which pleased his mother because it meant he could get an education. There Keon came under the tutelage of coach Bob Goldham and rounded out his game. He had never focused on defensive play, but by the end of his St. Michael's days, he was equally good with or without the puck.

He was invited to Maple Leafs training camp in September 1960 at age 20; the invitation came although Imlach frowned upon juniors jumping directly to the big club and had him ticketed for the American Hockey League. But Keon played so well in scrimmages and preseason games that, as Imlach later said, "There was no way he could be kept off the team."

Toronto had traded for Red Kelly late in the 1959-60 season, so the addition of Keon gave the Maple Leafs two excellent two-way centers. That allowed Toronto to compete against the NHL's top teams and helped launch a dynasty.

Keon centered a line with Dick Duff and captain George Armstrong as a rookie, and his skill and effort quickly made him a fan favorite. With 20 goals in 1960-61, he began a streak of six consecutive 20-goal seasons. In 1961-62 he was named to the NHL Second All-Star Team and won the Lady Byng Trophy for sportsmanship. Like Kelly, he played a hard, clean game; Keon won the Lady Byng again in 1964 and was frequently among the top vote-getters for the trophy during his first 11 NHL seasons.