Legendary hockey reporter Stan Fischler writes a weekly scrapbook for NHL.com. Fischler, known as "The Hockey Maven," shares his humor and insight with readers each Wednesday.

This week, Stan traces the tragic tales of two hockey stars of different eras who had one common thread: After equally brilliant hockey exploits, each died in avoidable plane crashes. Ironically, the mysteries involving their deaths have never been solved.

You simply could not make this up.

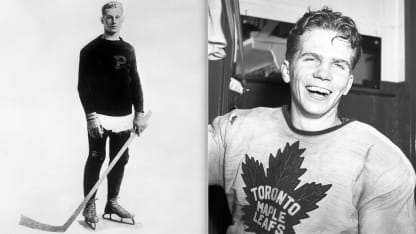

Two of the most significant hockey players from two separate eras died in avoidable plane crashes, and in each case a shroud of mystery has surrounded the respective disasters. To this day, only theories surround the deaths of an American hero, Hobey Baker, and his counterpart from Canada, Bill Barilko.

According to Baker biographer Tim Rappleye, during the years immediately preceding World War I, Hobey "was America's most dashing athlete and the pride of Princeton University. It was hockey that elevated Hobey to sports immortality."

To a generation of Canadians -- and this American author -- Barilko was no less glamorous. Throughout the spring and summer of 1951, he savored his role as the All-Canadian hockey hero. Just four months after he scored one of the most spectacular winning goals in Stanley Cup Playoff history, Barilko died. Like Baker, he ignored warnings to not fly that fateful day.

This much is indisputable. Baker, then a high-ranking World War I Allied airman, died when his Spad pursuit fighter plane crashed during a test run only days after an armistice had been declared, signaling the end of the five-year conflict.

What's more, there was no military reason for Capt. Baker's flight. He could have taken the train to Paris and eventually sailed to New York, bidding farewell to his Doughboy's khaki. In fact, Baker's Princeton professor and good friend, Donald "Heff" Herring, was right there turning thumbs down to his buddy's proposed flight.

"Baker brushed aside Herring and headed to the hangar with shouts of protest in his wake," Rappleye wrote in "Hobey Baker -- Upon Further Review."

Nor would Barilko pay heed to those fearing his demise. His mother cautioned her fearless son not to fly with his friend, dentist Henry Hudson, on a fishing trip to Rupert House on James Bay in northern Quebec. And before their ill-fated flight home to Timmins, Ontario, they were warned to wait another day so that the adverse flying weather conditions could clear. Like Baker, they dismissed the warnings out of hand.

Kevin Shea, author of "Barilko, Without a Trace," revealed that the pair planned to fly the dentist's seaplane to Seal River off James Bay. On their return to Timmins, they would stop off at Rupert House. That's when they were warned of an approaching storm were invited to remain another day, or until the storm faded away.

"They were anxious to get home," Shea wrote, "where they expected to stay that afternoon. They took off for home and no one ever saw them again."

Capt. Baker, who was scheduled to be discharged from Air Force duty in a matter of weeks, started the engine on his Spad.

"While it was warming up," Herring said, "Hobey gave me his promise once more that he would fly straight out to Pont-a-Mousson and back, a 40-mile-trip and land without acrobatics."

Said Rappleye: "It was a broken promise and would prompt many questions, the first of which is why did Baker take that ill-fated flight in the first place? The mystery of Hobey's death has confounded us all."

But there was nothing mysterious about Baker's ascent to hockey stardom. A natural athlete, the Philadelphia native began inspiring headlines while stickhandling at St. Paul's Boarding School in Concord, New Hampshire. He was an all-sports ace, but hockey brought him the most attention.

At 14, Baker made the school's varsity team and caught the eye of Manhattan sports fans when St. Paul's played "home games" at Saint Nicholas Arena, north of Times Square. His unbridled speed enthused fans more than any other young hockey prodigy.

"Saint Nicholas -- the forerunner to Madison Square Garden -- is where Hobey became America's first hockey superstar," Rappleye wrote. "He spent four years as a star for St. Paul's varsity, leading them to frequent victories over Ivy League varsities."

Not surprisingly, Baker's game grew at Princeton. His dazzling, dipsy-doodle, end-to-end rushes never failed to lift fans out of their seats. Soon, the Tigers were invited to Montreal, where chants of "Hobey, Hobey, Hobey" were a testament to his popularity north of the border, not to mention intense hockey towns like Boston, where his visit never failed to fill the then-new Boston Arena.

A write-up in the Boston Journal unequivocally observed that Baker was "without a doubt the greatest hockey player ever developed in this country or Canada."

Following graduation, Baker made the natural segue to the St. Nicholas Club. During the 1914-15 season, they defeated everyone they faced at a time when amateur hockey in New York was of the highest quality. (The NHL didn't plant a franchise in Manhattan until the New York Americans in 1925.)

As much as Baker adored being an idol of the crowds, he became increasingly aware of World War I. Before the United States entered the fray, he enlisted in the Air Force and after several red tape delays wound up, like Rappleye mentioned, "eager to fight the Huns in mortal combat."

Barilko took another route to fame, By the fall of 1946, the 19-year-old had so impressed Toronto Maple Leafs scouts with his defensive potential that hockey boss Conn Smythe shipped him to Hollywood of the Pacific Coast Hockey League. At the time, graduation for Bill to "The Show" seemed at least two or three years away.

Then, the kid from Timmins got lucky. He was teamed on Hollywood's defense with former NHL Hart Trophy-winner Tommy Anderson, who took Barilko under his wing. When Smythe needed some reinforcements during the 1946-47 season, he phoned Anderson about Barilko.

"He's green," Anderson said, "but he's willing and he learns fast."

On Feb. 6, 1947, Barilko made his NHL debut against the Stanley Cup champion Montreal Canadiens. The Maple Leafs lost 8-2, yet Barilko won favorable notices for his thundering body checks. Two nights later, he scored his first goal in a 5-2 win against the Boston Bruins at Maple Leaf Gardens and impressed Jim Vipond of the Toronto Globe and Mail.

"Barilko played as though he intended staying in the NHL for a long time," Vipond wrote. "He has the ability to hit an opposing player squarely and handed out several jolting checks. He sent Milt Schmidt flying over his shoulder and showed nice timing."

In no time at all, Barilko became among the most popular Maple Leafs because he had flash, dash and bash. One of his nicknames was "Bashin' Bill" and another was "Snake Hips" because of his unique way of body checking.

Teammate Bill Ezinicki, then the best body checking forward in the League, delivered a professional's eye view to author Jack Batten in "The Leafs of Autumn."

"Barilko is better at giving the hip than anybody in the League," Ezinicki said. "A guy'd come down the ice with the puck and he'd think he was safely past Billy. Then, all of a sudden -- wham! Billy'd catch him with the hip. Billy could move sideways quicker than any defenseman. That was his ace."

As Bill honed his game to sharpness, the Maple Leafs won three straight Stanley Cup championships from 1947-49, but the best was yet to come. Toronto set new team records with 41 wins and 95 points in 1950-51, defeated Boston in the semifinals and reached the Stanley Cup Final against Montreal, taking 3-1 lead in the best-of-7 series. The potential Cup-winning game was played at Maple Leaf Gardens on April 21, 1951.

The 2-2 tie drifted into overtime and just short of the three-minute mark, Toronto controlled the puck behind Montreal's goal. Suddenly, it skimmed out toward the left side of the blue line. Barilko seized the moment, charged, and -- virtually in full flight -- shot the puck over goalie Gerry McNeil for the Cup-winner.

"It seems unbelievable," said Bill Juzda, Barilko's defense partner. "One minute we were carrying him off the ice and the next minute he was gone."

When the plane carrying Barilko and Dr. Hudson failed to return to Timmins, the largest air search in Canadian history was launched but to no avail. Historian Eric Zweig remembered in his oral history, "The Toronto Maple Leafs," that hope they would be found extended into the fall of 1951.

"Conn Smythe offered a $10,000 reward to the person who found him ... or recovered his body," Zweig reported, "but it would take until the beginning of June in 1962 before the wreckage of the plane -- and the bodies of Bill Barilko and Dr. Henry Hudson -- were finally found."

How did the crash occur? Nobody knows.

Said Shea: "Even today, there is no clear answer as to what happened. I believe it was a reckless pilot who insisted on flying when conditions weren't appropriate."

Ditto for the illustrious Hobey Baker. When his Spad's engine failed, he tried to return to the field with a nose-down maneuver. It didn't work and he died as three officers lifted him out of the plane.

"Save once, I never saw Hobey's face without the appearance of life in it, and that once was the moment he died in my arms," Herring said.

"The end of Hobey's life remains a riddle," Rappleye concluded.

And so, it is for another hockey champion, Bill Barilko.