In the summer of 1988, Pat Kelly thought he was ready to get out of professional hockey.

After 36 years in the business, including the previous five seasons coaching the Peoria Rivermen of the International Hockey League, Kelly returned home to Charlotte, North Carolina, believing at 52 years old, it might be time to try something new. Then, he got a phone call from Henry Brabham.

ECHL grows into starting point toward NHL

Class AA minor league helped develop more than 600 players

"Mr. Brabham called me and wanted to know if I was interested in forming a league," Kelly said. "I said, 'No. I think I'm going to get out of hockey.' "

But Brahham, who owned the Virginia Raiders of the Atlantic Coast Hockey League (ACHL) when Kelly coached them prior to moving on to Peoria in 1983, was persistent.

"He must have called me eight to 10 times that week and said, 'I know your birthday is coming in September. Come on up and play some golf,' " Kelly said. "So the wife and I went up [to Roanoke, Virginia] and he offered me the job to be the commissioner of the league."

The new five-team league would be called the East Coast Hockey League. At the time, he had no idea it would grow into what is today, a premier Class AA developmental league that has sent 606 players, as well as a host of coaches, on-ice officials, trainers and equipment staff, on to the NHL.

It now includes 27 teams spread across North America, from Manchester, New Hampshire, and Fort Myers, Florida, in the Eastern Conference to Allen, Texas, and Anchorage, Alaska, in the Western Conference. It even outgrew its name, prompting a simplified official rebranding to the ECHL in 2003.

"I felt if we could ever get to eight, maybe 10 teams, that would be good because that was how the old Eastern Hockey League was, and we got to 11 [teams] in the first three years," said Kelly, who along with Hockey Hall of Famer Mark Howe will receive the Lester Patrick Trophy for outstanding service to hockey in the United States in Philadelphia on Nov. 30. "I didn't think it would grow like that. I knew it would be a [Class] AA hockey league, but I didn't know it would get 600 players go on to the NHL, [along] with referees, coaches and marketing guys, radio guys and trainers."

Over the years, some teams moved or folded and were replaced by others, but the quality of play and the league's reputation continued to grow.

"There's some good players in that league," said Shane Harper, who became the 600th ECHL player to reach the NHL when he appeared in the Florida Panthers season opener against the New Jersey Devils on Oct. 13. "It's exciting. It's pretty darn offensive. There's guys there every year you see that go up to the American Hockey League and do well, so there's definitely a lot of good players in that league."

In the beginning

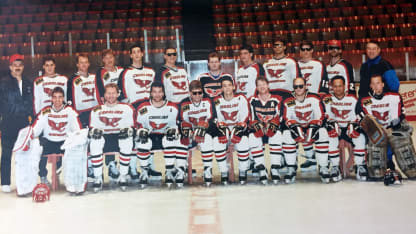

The ECHL was formed from three teams salvaged from the defunct ACHL and All-American Hockey League (AAHL) -- the Carolina Thunderbirds, Johnstown Chiefs and Virginia Lancers -- and two newly-formed franchises, the Erie Panthers and Knoxville Cherokees. Brabham owned the Chiefs, Lancers and Panthers. Bill Coffey owned the Thunderbirds in the AAHL, but sold them to John Baker and established the team in Knoxville.

The five teams each played 60 regular-season games in 1988-89, the league's first season. That made for some grueling travel. Even after the ECHL expanded to eight teams with the addition of the Greensboro Monarchs, Hampton Roads Admirals and Nashville Knights in 1989-90, the schedule took its toll with demanding stretches that sometimes included eight games in 11 days.

"There was always a small number of teams, so you were playing [each other] 10 to 15 times a year," said Florida Panthers assistant Scott Allen, who played for the Thunderbirds.

Players carried over from the ACHL and AAHL saw their pay cut as much as 40 percent, with the ECHL installing a salary cap to try to keep expenses to a minimum and stay afloat. To augment his salary, Thunderbirds left wing John Torchetti, now an assistant coach with the Detroit Red Wings, would take a shift driving the team bus on road trips.

"I think we got 11 cents a mile, and that's just what it took," Torchetti said. "If you drive 11 cents a mile and you drive a couple hundred miles, that was decent money back then."

One of Kelly's initial goals was to make minor league hockey family-friendly in order to rebuild fan interest, as well as to get the NHL to view the ECHL as a legitimate option for developing prospects.

"Minor league hockey sort of fell out of grade in the early and mid-'80s," Kelly said. "When we formed the league in '88, the [International Hockey League] was down to six or eight teams and there wasn't much other hockey being played. My first meeting with Mr. Brabham and Mr. Coffey was [to see] if we could get hockey back where it wasn't fighting and four-hour games and players going up in the stands after fans.

"I said, 'We've got to get moms and dads to come back to bring their sons and daughters to the game and get rid of the brawling on the ice that was going on in all of these minor league games.'"

When Kelly was a player-coach in the Eastern Hockey League in the 1960s and 1970s, suspensions would often get overturned by a vote of league owners. With Brabham's and Coffey's backing, Kelly instituted stricter rules that called for suspensions for players with repeated misconduct and game misconduct penalties, as well as for coaches whose players left the bench to join fights.

That didn't mean the ECHL didn't have its share of tough players in its early days, but there were fewer whose main purpose was to fight.

"We had some guys that could handle themselves," said Winnipeg Jets goalie coach Wade Flaherty, who helped Greensboro win the 1989-90 championship and went on to play in 120 NHL games. "But it wasn't like 'Slap Shot,' the old Federal League, where there were line brawls. I actually don't recall one line brawl that happened. So I think that's maybe where they made the change where they were trying to concentrate on the hockey."

Kelly's message was clearly sent during the inaugural ECHL final between Carolina and Johnstown, when Carolina was forced to play Game 7 with 11 skaters because three players were suspended and others were injured.

The Chiefs, who were named after the fictional Charlestown Chiefs from the 1977 movie "Slap Shot," had their full roster and a capacity crowd for the deciding game at Cambria County War Memorial Arena, where some scenes from the movie were filmed.

"When we came in for the morning skate, the line was out the door and down the block, four, five people wide," Allen said. "It's not a big building. People were actually sitting in the stairwells. The seats were all filled. It was jam-packed."

Despite being shorthanded, Carolina won 7-4 to become the ECHL's first Riley Cup champions.

"At the time, it was funny because I remember changing up and just going, 'Whoever's not tired, go. Stop asking. Just rotate out the door,'" Torchetti said. "It was amazing. We were either four [defensemen] and seven [forwards] or five [defensemen] and six [forwards]. I can't remember which one it was. But, at one time, someone was like, 'Are you taking a penalty for real right now? What are you trying, to get a rest?' That was the fun in the locker room."

The following season, Johnstown goaltender Scott Gordon became the first ECHL alumnus to reach the NHL when he made his debut with the Quebec Nordiques.

Southern exposure

Kelly served as ECHL commissioner for eight seasons before being named commissioner emeritus and being succeeded by Rick Adams. The league also honored Kelly by changing the name of its championship trophy from the Riley Cup (named after former AHL president and Pittsburgh Penguins general manager Jack Riley) to the Kelly Cup.

The first winners of the Kelly Cup were the South Carolina Stingrays in 1996-97. That team, which continues to play in North Charleston, included Colorado Avalanche coach Jared Bednar, a defenseman, and Washington Capitals pro scout Jason Fitzsimmons, who was the backup goaltender.

Fitzsimmons and Bednar each would later coach the Stingrays and kept homes in the Charleston area.

"When I moved down and I started playing for [coach] Rick Vaive on the Stingrays in the mid-'90s, I got off the plane and it was 75 degrees and I still live there," Fitzsimmons said. "I fell in love with that city. A great hockey city."

By then, the ECHL was a 23-team league that had spread its footprint further into the South with a division that included the Tallahassee Tiger Sharks, Birmingham Bulls, Louisiana Ice Gators, Mobile Mysticks, Mississippi Sea Wolves, Pensacola Ice Pilots, Baton Rouge Kingfish and Jacksonville Lizard Kings.

The Stingrays were joined in the East Division by Knoxville, Hampton Roads, the Richmond Renegades, Roanoke Express, Charlotte Checkers and Raleigh Icecaps. The North Division included Johnstown, the Columbus Chill, Peoria Rivermen, Dayton Bombers, Wheeling Nailers, Toledo Storm, Huntington Blizzard and Louisville Riverfrogs.

But it was in the South where the ECHL made its biggest inroads, even if all of the teams didn't last.

"We've got markets like Charleston or even down to Fort Myers, to name only a couple, that a generation ago there were no kids playing youth hockey and they had no facilities," current ECHL commissioner Brian McKenna said. "But as a result of minor league hockey coming there, it not only entertained the fans but introduced a whole generation to the sport. Now, in some of those communities, hundreds of kids are playing youth hockey and across the South, tens of thousands of kids are playing hockey that probably 25 years ago would never have even thought about playing.

"The level of play in a lot of those communities is such that kids are playing at a very high level, competing on a national level and getting scholarships to Division I programs as well."

The ECHL's level of play also continued to rise. Colorado College coach Mike Haviland, who played in the ECHL with the Richmond Renegades and Winston-Salem Thunderbirds in 1990-91, noticed a significant difference when he returned to the league as an assistant coach with the Trenton Titans in 1999-2000.

"It was like night and day to see the evolution of that league and how good it really was," Haviland said. "People that didn't know anything about the East Coast Hockey League didn't know how good it really was and still is. When you're there as a coach and a player and even referees, everybody is trying to get to the American League and the NHL, so everybody is working extremely hard."

Haviland went on to coach the Atlantic City Boardwalk Bullies (formerly Birmingham) to the Kelly Cup in 2002-03 and the Titans to a championship in 2004-05. His Boardwalk Bullies own the dubious distinction of having the Kelly Cup's base fall apart during their raucous celebration.

"They put a big dent in it and they broke it and we tried to put it back together as best we could," Haviland said. "I don't think Pat Kelly and Brian McKenna were very happy with us, but for a lot of guys it was their first time winning a championship and I don't care what level you're at, it's something special. I don't know exactly what happened. I just know when it got back to me, it was not in very good shape."

Allen returned to the ECHL as an assistant and then as coach with Johnstown from 1996-97 to 2001-02. Although the league has evolved over the years, he believes, "There's always been good players in the ECHL."

"The other night I was on the bench against [the New Jersey Devils] and I look over and there's Vern Fiddler," Allen said. "I coached against Vern Fiddler when he was playing for the Roanoke Express in the ECHL and he's had a tremendous career in the National Hockey League. Not every player needs to play in the ECHL, but there are some guys who certainly do need to play there and enhance their abilities and move up the ladder. It's all about development."

Going West

The ECHL's next big move came in 2003-04, when it went coast to coast by absorbing the Alaska Aces, Bakersfield Condors, Fresno Falcons, Idaho Steelheads, Long Beach Ice Dogs and San Diego Gulls from the defunct West Coast Hockey League. It also added the expansion Las Vegas Wranglers to reach its high point of 31 teams.

That peak lasted one season, with the teams in Cincinnati and Columbus going on voluntary suspension and Greensboro, Roanoke and Richmond ceasing operations before the 2004-05 season. That was also the season Baton Rouge moved to Victoria, British Columbia, to become the ECHL's first Canada-based team.

The Aces were intriguing to Anchorage native Scott Gomez when he was looking for a place to play during the work stoppage that led to the cancellation of the 2004-05 NHL season. Gomez, who won the Stanley Cup with the Devils in 2000 and 2003, briefly traveled to Moscow with former Devils teammate Igor Larionov and considered playing in Russia, but ultimately decided to take advantage of the chance to play in his hometown.

"I looked at it as a terrific way to give back," he said. "That's what I did, but the decision was easy because I had about six buddies on the team and we hadn't played together since we were kids."

Gomez had been branded with the "silver spoon" moniker by some of his Devils teammates because he never played in the minor leagues before jumping to the NHL. He got the full experience with the Aces, with long road trips to Boise, San Diego, Fresno, Bakersfield, Long Beach and Las Vegas.

"After that, I was like, 'There will never be the 'silver spoon' thing again,'" Gomez said.

But Gomez and the rest of the Aces didn't mind the trips to Las Vegas.

"People don't realize that being in Alaska, when we went on the road we'd stay for a while," he said. "We'd be in Las Vegas for eight days and play three games because you're not going back after one game. And if you're in Vegas for eight days, the Alaska boys are going out. It was nuts. What a great time we had. The experience and the hockey was great. The competition was better than I expected."

Gomez won the ECHL scoring title with 86 points and was named the league's most valuable player. His Aces linemates that season, Chris Minard (Penguins and Edmonton Oilers) and Charles Linglet (Oilers), eventually had brief stints in the NHL.

"The league was good to me," Gomez said. "It was first-class all the way."

Gomez returned to the Aces when the start of the 2012-13 NHL season was delayed by another labor dispute. By then, the ECHL was down to 23 teams.

It was at 20 teams the previous season, but added four in expansion -- the Evansville Icemen, Fort Wayne Komets, Orlando Solar Bears and San Francisco Bulls -- and lost the Chicago Express, which withdrew from the league. The Las Vegas Wranglers were still around, but suspended operations following the 2014-15 season when they had trouble getting a new lease at their arena; they abandoned their efforts to return the following year with plans already forming for Las Vegas to bid for an NHL expansion team, which begins play next season.

Johnstown was the last of the five original ECHL markets to lose its team when the Chiefs left for South Carolina after the 2009-10 season and became the Greenville Road Warriors (now the Greenville Swamp Rabbits).

"What happened is the league outgrew Johnstown," Allen said. "If you go back and watch video from when we won the championship [in 1988-89], there's nothing on the dasher boards or anything like that. They started selling dasher board ads, so new teams that came into the league could sell them for so much. Johnstown said, 'Hey, this is great. We can sell this for $200.' Meanwhile other teams were getting $5,000.

"Johnstown is a mom-and-pop type of operation as far as the businesses and stuff, and it was tough to continue. So, unfortunately, the league just outgrew it."

Goalies and dreams

McKenna acknowledges franchise stability has been a problem, but believes the league has begun to settle down. Prior to the 2014-15 season, the ECHL added seven teams from the defunct Central Hockey League - the Allen Americans, Brampton Beast, Rapid City Rush, Missouri Mavericks, Quad City Mallards, Tulsa Oilers and Wichita Thunder - and the expansion Indy Fuel.

The league is at 27 teams now, and "the immediate goal" is to get to 30 during the next 12 to 18 months to match the current totals in the NHL and AHL.

"We want to get to that 30-team model and keep it there, but we have a lot of teams now that have been in existence for 15, 20, 25 years in their current markets," McKenna said. "Even smaller markets, places like Wheeling, West Virginia, have been in our league and have been valued members for many years. I think [team movement] is a function of minor league sports. … If better opportunities, newer facilities become available, then there will always be some movement at the margins, but certainly a lot less than we've seen in the last couple of decades."

Regardless, the NHL and AHL clearly value the ECHL as a developmental league. ECHL teams have affiliations with 26 of the NHL's 30 teams and 26 of the AHL's 30 teams.

Of the 606 former ECHL players to reach the NHL, 40 have their names on the Stanley Cup. In addition, six of the 30 current NHL coaches have played or coached in the NHL.

That includes the Nashville Predators' Peter Laviolette, who coached the Carolina Hurricanes to the Stanley Cup in 2006, the Buffalo Sabres' Dan Bylsma, who coached the Penguins to the Cup in 2009, the Minnesota Wild's Bruce Boudreau, the Calgary Flames' Glen Gulutzan, the New York Islanders' Jack Capuano and Bednar, who won the Calder Cup last season with Lake Erie before being hired by Colorado.

"I owe everything to that league for giving me that chance to get into coaching and learn the trade and really develop," said Haviland, who won the Stanley Cup as an assistant with the Chicago Blackhawks in 2010. "Obviously, it helped me prepare for future years."

McKenna estimates that "about 12-13 percent" of the players on NHL rosters this season got their start in the ECHL, as well as "about 20 percent" of the coaches and their assistants. Additionally, "one-third" of the referees and linesmen in the NHL worked in the ECHL initially.

Haviland and Allen point out that the equipment managers and medical trainers from the ECHL teams they coached have also made it to the NHL.

As far as the players, McKenna believes the ECHL's stricter restrictions on veterans in the past 15 to 20 years have helped aid development. Teams are limited to four veteran skaters (260 or more regular-season games in professional hockey) on their active rosters.

"We're trying to make it a league where players can come and experience good competition, good coaching and have an opportunity to move up," McKenna said. "Not all do and those that don't, by having the veteran rule in place, it enables other young players to come in and replace those that move along."

Notable ECHL alumni in the NHL include reigning Vezina Trophy winner Braden Holtby of the Washington Capitals, 2012 Conn Smythe Trophy winner Jonathan Quick of the Los Angeles Kings, New York Rangers defenseman Dan Girardi, Ottawa Senators left wing Mike Hoffman, Philadelphia Flyers defenseman Mark Streit and Devils right wing PA Parenteau.

The ECHL's biggest impact has been with goaltenders. In all, 25 goalies who have played in the NHL this season played in the ECHL earlier in their careers.

Holtby, who played 12 games for South Carolina in 2009-10 and also played in the ECHL All-Star Game that season, said it "brought a lot of humility to things."

"You kind of realize that you have to work for what you get if you're going to get something in pro hockey," he said. "I met a lot of great people there that I still keep in touch with, which is pretty cool. It's a tough league. I've always said that was the toughest league, the AHL is second and the NHL gets a little easier as a goalie."

Having played there himself, Flaherty believes the ECHL is a great training ground for young goaltenders. Jets goalie Michael Hutchinson got his start with the Reading Royals in 2010-11; prospect Jamie Phillips, 23, began his pro career with the Tulsa Oilers this season and was the ECHL's goaltender of the month for October.

"The thought process is [that] you send a goalie down there to play," Flaherty said. "The best thing that helps a goaltender is being in the net in game situations. [Phillips] is out of college, but we want him playing. You want him to go down there and play as many games as he can."