As part of the NHL's Centennial Celebration, longtime hockey reporter and analyst Stan Fischler, "The Hockey Maven," will write a biweekly scrapbook for NHL.com. The scrapbook will look at some of the strange-but-true moments from the NHL's first 100 years. Here is his fifth contribution:

Americans enjoy one last, long hurrah

1938 playoff victory vs. Rangers was highlight of long-ago New York rivalry

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

Everything about the New York Americans-New York Rangers rivalry was bizarre. But nothing was more unpredictable than their involvement in the longest hockey game ever played in New York City.

Before getting to that seemingly endless match on March 27-28, 1938, a few historical notes are in order:

* The Americans, owned by a bootlegger named William "Big Bill" Dwyer, entered the NHL a year before the Rangers and played their games in the spanking new Madison Square Garden on Eighth Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets. The then-filthy rich Dwyer paid a handsome rental to the Garden.

* So successful were the Americans that the bosses at MSG decided to launch their own team, the Rangers, who played rent free.

* The rivalry between the teams was volcanic even in its quietest moments.

* The Rangers became the blue-blooded two-time Stanley Cup champions; within five years, the Americans were endlessly broke and often the NHL's laughingstock.

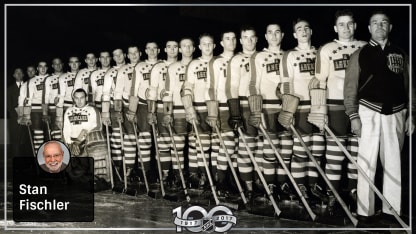

© B Bennett/Getty Images

The 1938 New York Rangers with Lester Patrick standing fourth from the left (Photo courtesy of Getty Images)

The Americans sure had their laughs, all right. But that's not surprising, considering how they arrived on Broadway in the first place. Actually, their saga began with a players' strike by the Hamilton Tigers in the spring of 1925.

Angry because they were denied a postseason bonus, the Tigers refused to show up for the playoffs after finishing first during the regular season. NHL President Frank Calder suspended the strikers and eventually helped move the franchise into the just-completed Garden. Poof! Just like that, the Tigers became the New York Americans.

It was a sweetheart deal for the Garden bosses because the Americans agreed to pay rent for use of the arena throughout their first season. Dwyer didn't mind since he was raking a fortune from his bootleg booze business. What's more, he never imagined that the Garden's high command would slip another NHL team into the spanking new arena a year later.

But the Americans were drawing so well that the MSG bosses decided to install their own (rent-free) team in time for the 1926-27 NHL season. The new team, known as the Rangers, made their world premiere on Nov. 16, 1926. In no time at all, the Rangers managed to steal the Americans' thunder and become the Big Apple's hockey darlings.

The rivalry extended to the adjoining front offices at 309 West 49th Street. As befitting someone whose nickname was "The Silver Fox," Rangers boss Lester Patrick exuded a distinguished facade and was respected by the Manhattan media. By contrast. the Americans rambunctious leader, Mervyn "Red" Dutton, was as fiery behind the desk as he was behind the bench. Of course, Patrick had an advantage since the Rangers were well-loaded with dough. In contrast, Dutton was trying to make ends meet with a bare-bones budget after Dwyer lost his fortune with the end of Prohibition; the NHL wound up taking control of the franchise and letting Dutton run it.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

Mervyn "Red" Dutton, left, signs a contract to be the manager of the Americans on April 25, 1935 in New York, New York. William A. Dwyer, the son of the owner, looks on. (Photo courtesy of Getty Images)

Despite the lack of resources, Dutton still managed to ice a competitive team. His Americans finished second in the NHL's Canadian Division in 1937-38, and his protégé, Sweeney Schriner, placed seventh in scoring. "What made me so proud," Dutton said, "was that I signed Schriner to his first pro contract. I brought him in along with Art Chapman and Lorne Carr and together they made one of the greatest lines in hockey."

By that time the Rangers-Americans rivalry was more than a decade old and more intense than ever. "When you think about it," recalled Carr, "the two teams were too close for comfort. We had shared the Garden for many seasons, and it created a real friction between the two teams. It made us natural rivals, like the New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers in baseball. To put it mildly we were bitter rivals. Frankly, we hated each other.

"We would play regular-season games with such intensity that you would think they were the seventh game of the Stanley Cup Final. If we passed each other on the streets, we would just look away. The Rangers had their watering holes and we had ours, and we made sure they weren't anywhere near each other."

When the 1937-38 regular season concluded, the Americans faced the Rangers in a best-of-3 quarterfinal series. Oddsmakers had trouble picking a favorite because Dutton had sagely signed several over-the-hill veterans who would eventually make it to the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Yet while they superficially may have looked like retreads, players like defensemen Hap Day and Ching Johnson, not to mention forward Nels Stewart, still had the goods. By contrast the Rangers were in rebuilding mode and featured young stars such as Lynn Patrick (Lester's oldest son), Bryan Hextall and brothers Neil and Mac Colville.

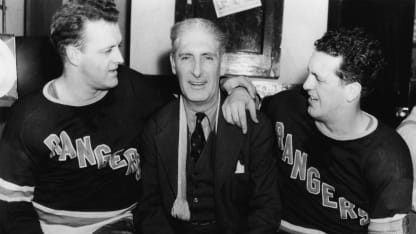

© B Bennett/Getty Images

Lester Patrick (center) poses with his sons, Rangers players Lynn (left) and Muzz (Photo courtesy of Getty Images)

If there could have been a "Perfect Storm" of a playoff, this was it.

The Americans won the opener 2-1 on Johnny Sorrell's goal at 1:25 of double overtime. The Rangers rebounded with a 4-3 win, setting the stage for the climatic finale on March 27, 1938, at the Garden. Not surprisingly, it attracted the largest crowd of the season; the listed attendance of 16,340 exceeded the Garden's seating capacity of 15,925.

"By dawn of the 27th, lines had started to form outside the balcony ticket windows on 49th and 50th streets," wrote Sport Life Magazine editor Bruce Jacobs. "The gallery was packed long before the teams skated out."

The first period wasn't without its own incredible episode, engineered by a female Rangers fan disappointed with the scoreless match. Out of nowhere, the woman stormed goal judge Charles Porteous and pressed the red light buzzer when she thought the Rangers had scored. Eventually, the police stepped in to restrain her, and referees Bert McCaffery and Ag Smith restored order on the ice.

The Rangers scored two goals in the second period, inspiring Dutton to dramatically alter his strategy. In the third, he used a lineup of five forwards. The scheme worked; Carr and Stewart scored to tie the game 2-2 and force overtime. By the end of three sudden-death periods, it was well past 1 a.m. This prompted one Americans fan to return to his seat from a corner tavern.

The gentlemen had left the arena when the Rangers were up 2-0. While downing yet another beer in a Broadway bistro, he asked a newcomer, "How da game wind up?"

"Wind up?" the other replied. "Why, they're still playing. The score's 2-2!"

The fan grabbed his hat and ran back to the Garden as referee Smith dropped the puck to start the fourth overtime.

Saturday had turned to Sunday and the players, who had skated through 120 minutes of hockey, were exhausted. Some had already lost 10 pounds from the marathon ordeal.

Dutton decided to open the fourth overtime with his top line of Schriner, Chapman and Carr. One newsman in the press box realized that Carr's rookie NHL season, 1933-34, had been spent with the Rangers; the kid from Saskatchewan had scored no goals, no assists, no points in 14 games. That explained why the Rangers had no qualms about trading him to the Americans.

By the time the puck dropped to begin the fourth OT, players on each team were running on fumes. "If ever I had a test of my mental and physical conditioning, this was it," Carr said. The fans who remained had their own problem: The Garden's concession stands had run out of food.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

Rangers forward Lynn Patrick (Photo courtesy of Getty Images)

Carr, a right wing, faced Rangers left wing Lynn Patrick. As play unfolded from the opening faceoff, the puck eventually skimmed into the Rangers zone where Patrick retrieved it, looking for launch a counterattack.

"Lynn tried to get a fast break on me, but I intercepted the puck," Carr said. "Right then, I had to make a quick decision. In retrospect I might have passed but my first instinct was to shoot at Rangers goalie Davey Kerr. And that's what I did. My shot beat him with only 40 seconds gone and let me tell you, it was a terrific feeling. It was hard to believe but at this hour in the morning we were too exhausted to celebrate. By the time we got dressed it was past 2 a.m."

Nobody was more exhilarated than Dutton. "That," he concluded, "was the greatest thrill I ever got in hockey. The Rangers had a high-priced team, and beating them was like winning the Stanley Cup to us."

It was the Americans' only measure of revenge against the Rangers. "The contest couldn't have been more adaptable to drama had a script been written by Alfred Hitchcock," Jacobs wrote.

Then again, there even could have been a perfect ending had the Americans gone on to win the Stanley Cup. However, the favored Americans were eliminated by the Chicago Black Hawks in a best-of-3 semifinal and never achieved such lofty heights again.

By the end of the 1941-42 season, Dutton had lost nearly all his players to the Canadian Army and other branches of the services during World War II. He was forced to fold the club just when he had anticipated rebuilding his franchise after the war.

"The way I envisioned it," he said, "in the long run we were going to come out all right. A couple more years and we would have run the Rangers right out of the rink!"

And so, the Americans vanished and a glorious New York-New York hockey rivalry came to a sad close.

But, as the bromide goes, it sure was fun while it lasted.