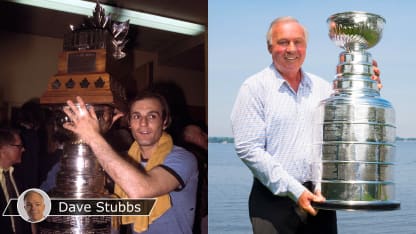

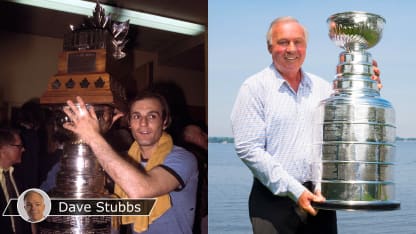

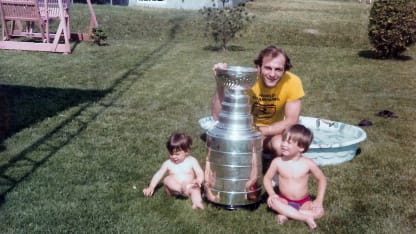

Guy Lafleur and his wife, Lise (third from left), at their home on June 6 with the Stanley Cup. With them are son Mark (far right) and his girlfriend, Natacha (far left); and son Martin with his wife, Angelica, and their 3-year-old daughter Sienna Rose.

But the few hours he spent with the Stanley Cup on Sunday marked Lafleur's first chance to truly share hockey's grandest prize with his family members, whom he views as his cornerstones: his wife, Lise; son Martin and his wife, Angelica; son Mark and his girlfriend, Natacha; and Martin and Angelica's 3-year-old daughter, Sienna Rose, Lafleur's only grandchild.

"A player's family doesn't receive the credit they deserve," Lafleur said, reflecting on the Cup's visit and the cancer battle he's waging, suggesting that his time with the trophy was more about his family and others than it was about himself. "And now Sienna Rose will always have a photo of herself with the Stanley Cup."

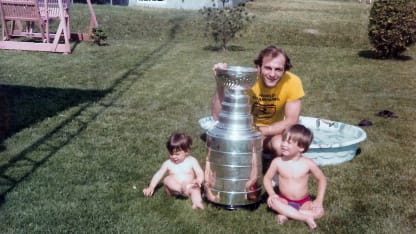

Lafleur was offered a day with the Cup in the summer of 2005, when the 2004-05 NHL season was canceled because of a lockout. Many former players who never had the opportunity enjoyed the chance, but Lafleur turned it down, telling Philip Pritchard, the Hall of Fame curator and so-called Keeper of the Cup, that more senior players should have it first, that his turn would come.

Sixteen years later, it did. Longtime friend Donnie Cape got the puck rolling with NHL Alumni Association executive director Glenn Healy and Pritchard, the NHL also lending its support.