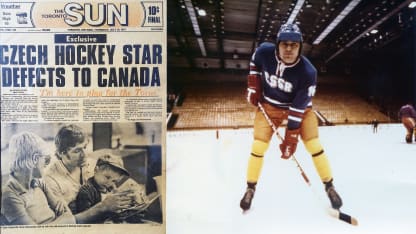

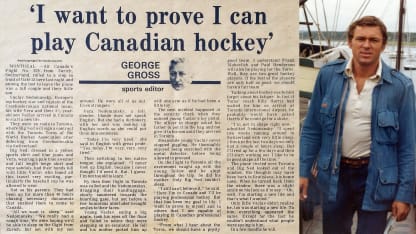

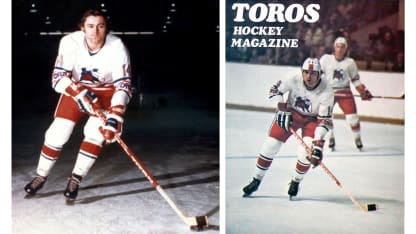

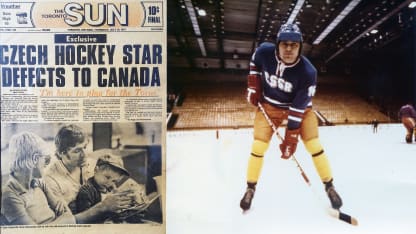

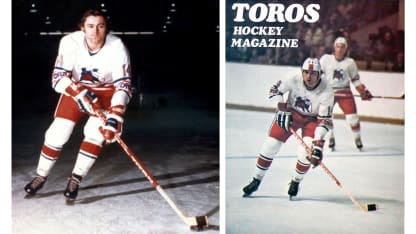

At no time during his flight from Switzerland to Montreal on July 17, 1974, bound for the Toronto Toros of the World Hockey Association, did he consider his role as a hockey pioneer, that his bold, even courageous move to Canada with his wife, Vera, and 3½ -year-old son, Vashi, would in time open the door to others from Eastern Europe and eventually change the face of pro hockey on this continent.

And never did Nedomansky, 75, imagine that he would be back in Toronto this week to be inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame.

"I am grateful and deeply honored by my election," Nedomansky said from his home in Palm Desert, California. "I didn't play to become a member of the Hockey Hall of Fame, I played because I loved the game. I always had small goals and tried to become better and better.

"When I made the decision to come to North America, I knew that I couldn't go back to Czechoslovakia. But I've never had any regrets about that move. I'm very happy with how it turned out. When you're a young man, you don't think about the history of your actions, that will come later on.

"It seems to me that this was such a long time ago. Since then, I've been through many changes, many situations, many jobs. My view is only one of looking forward. I don't look back because there were so many bad experiences. I'd rather not think about them."

BIG NED - Official Trailer from Vashi Nedomansky on Vimeo.

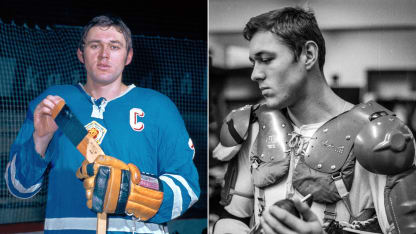

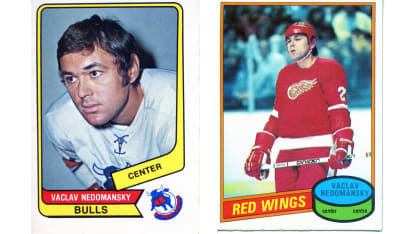

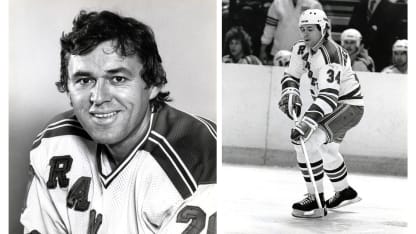

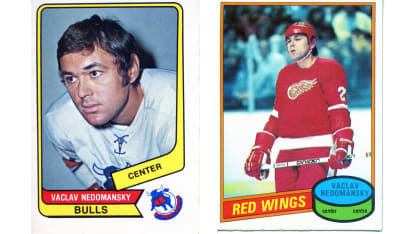

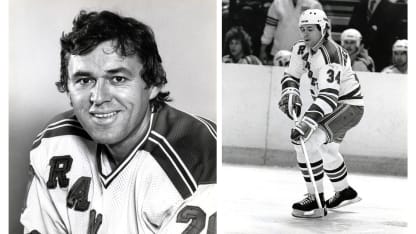

When he bolted his homeland for the West, Nedomansky, then 30, was regarded as the world's greatest hockey talent not skating in the NHL. "Big Ned" was a highly decorated, 6-foot-2, 205-pound center who could dominate a game at his natural position and easily play both wings and defense.

Born March 14, 1944 in Hodonin, a gifted athlete who as a boy excelled at soccer, tennis and basketball, Nedomansky began to focus on hockey as a 12-year-old in the new arena built in his hometown.

RELATED: [Nedomansky earned spot in Hockey Hall of Fame on, off ice, Mahovlich says]

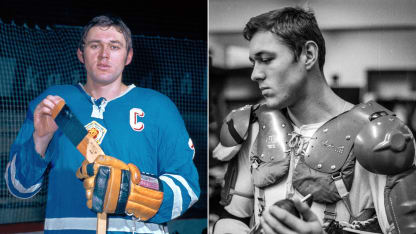

From the early 1960s, for 12 seasons, he was a brilliant talent with Slovan Bratislava of the Czech Elite Hockey League, four times the circuit's leading point-scorer. He would represent Czechoslovakia nine times at the IIHF World Championship from 1965-74, winning a gold, four silver and three bronze medals, and was on Olympic teams that won silver and bronze medals in 1968 at Grenoble and 1972 at Sapporo, respectively.

But the Soviet Union's invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 bitterly soured Nedomansky's life, as it did for so much of the population, and even his outlook on hockey. Trying to ignore ugly politics, in 1969 he elevated his already legendary status at home when he led the Czechoslovakian team in two World Championship victories over the Soviets, the eventual tournament winner. He says those wins, his country a huge underdog on the hockey rink and the global political stage, are among the highlights of his life.