Bernice Carnegie was crying tears of joy over the phone, thrilled and surprised by the day she thought would never come.

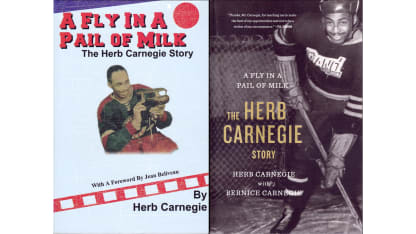

Herb Carnegie, her late father who several hockey historians regard as the best Black player never to play the NHL and a pioneer on and off the ice, was finally elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame in the Builder category.

The announcement Monday capped years of petitions drives, editorial campaigns and advocacy by current and former NHL players for Carnegie to be recognized by the Hall of Fame.

"This is so amazing," Bernice Carnegie said Monday. "For a long time, I just kind of put it out of my mind. There were so many people that worked so hard to try to bring it to their (the Hall's) attention, but it just didn't want to seem to happen. Every year when the announcement came out, news articles would come out and say, 'Herb's been forgotten, Herb's been forgotten.'"

Not anymore.

Not that he ever was by those who know his story, including his contributions as a player, an innovator and philanthropist, and what he endured to play the sport he loved.

"He paved the way for a lot of players from Tony McKegney to Val James to Mike Marson to Anson Carter to Wayne Simmonds and myself," said Anthony Stewart, a "Hockey Night in Canada" analyst who played 262 NHL games as a forward for the Florida Panthers, Atlanta Thrashers and Carolina Hurricanes from 2005-12.

"Players our age [who] go through issues of racism really appreciate what he had to go through, and it actually helped us in getting through that," Stewart said. "What we went through is nothing compared to what he went through."

Filmmaker Damon Kwame Mason conducted the last interview with Carnegie before he died on March 9, 2012, for "Soul on Ice: Past, Present & Future," an award-winning documentary on Black hockey history.