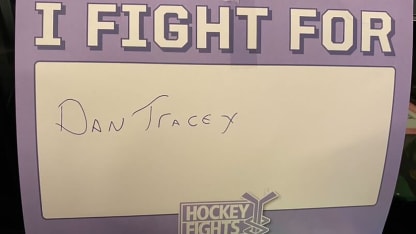

Worse yet, before last November was even over, I needed a new card.

A week or so before Thanksgiving, my brother-in-law, Dan Tracey, was diagnosed with glioblastoma, a brutal, unforgiving form of brain cancer. He died in August at age 59.

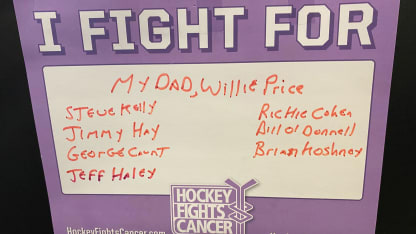

It clearly hit home for me, my wife, and our entire family, but I know Dan's story, unfortunately, is not unique. Cancer doesn't discriminate. From a professional athlete like Oskar Lindblom, now of the San Jose Sharks, to my dad and brother-in-law, to little kids, it does and can impact anyone at any time.

It's why

Hockey Fights Cancer

month, which starts today and runs through November, is so important to me and the entire League.

It's much more than all 32 teams holding Hockey Fights Cancer Nights, wearing purple jerseys and tape on their sticks, it's about raising awareness of every form of cancer and raising money in support of local and national level cancer programs, cancer research institutions, children's hospitals, player charities and local charities. A release sent out by the NHL today says Hockey Fights Cancer has an even more pointed impact -- focusing specifically on the human experience and supporting families, caretakers and people going through, living with and moving past cancer through various service of and by our national charitable partners.

In short, the money is being used to help all those impacted by cancer, because I have learned over the past several years, that though the person with the cancer is clearly the most impacted, they are not the only one.

Take Dan's story.

Dan was diagnosed right around last Thanksgiving when co-workers and his family started to notice he was acting odd. He would stare at his phone for hours while he was supposed to be working. One day he went to a different office of his company saying he got a text to be there. He didn't get a text. When he was diagnosed, he was given 12-18 months to live. He made it 10 months, but in no way did he live that whole time.

The first few months he seemed OK, but he and his wife had to make the drive in New Jersey from Jackson to Hackensack and back, sometimes five days a week a few weeks in a row, for treatment and some clinical trials. In addition to the heavy chemotherapy and radiation he was having, the 90-minute drive each way was taking a toll. His wife, Sue, and their daughter, Kristen, had to take time off from work, resulting in less income. Their entire lives were turned upside down. He was able to make a trip to Universal Orlando in May for his son, DJ's, birthday, but after returning, he slowly went downhill, and by early August, the family arranged for in-home hospice so he could spend his last few days there with an aide coming to the house. The doctors at one of the best cancer centers in this country were no match for his cancer. He died about a week later, spending the last few days bedridden in an almost comatose state.

It was no way for someone to live, and no way for someone to die.