The 2018 Hockey Hall of Fame induction is Monday. This class includes NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman, and Willie O'Ree, the first black player in the NHL, in the Builders category as well as former players Martin Brodeur, Martin St. Louis, Alexander Yakushev and Jayna Hefford. Here NHL.com staff writer Amalie Benjamin profiles O'Ree.

O'Ree has influenced generations on way to Hockey Hall of Fame

NHL's first black player, being inducted as Builder, continues to inspire youth to play game

Lou Vairo needed to prove a point. His friend, Ralph Dease, refused to play on Vairo's Brooklyn roller hockey team because he simply didn't believe black people played hockey. Vairo knew differently. He knew that, at that very moment in 1959, a forward named Willie O'Ree was taking the ice for the Boston Bruins. He could prove it: The Bruins were coming to town, playing the New York Rangers.

A side balcony ticket at Madison Square Garden cost 50 cents and, as Vairo recalled, "You'd sneak on the subway to get there."

So that's what they did.

RELATED: [O'Ree showered with social media posts]

"He came to the game and he saw Willie," said Vairo, director of special projects for USA Hockey. "He was so impressed that he joined our roller hockey team."

Dease may have been one of the first players affected by O'Ree, set to join the Hockey Hall of Fame on Monday in the Builders category, but he was far from the last. O'Ree not only broke the NHL's color barrier 60 years ago when he debuted for the Bruins on Jan. 18, 1958, but he returned to hockey in 1995 with the NHL/USA Hockey Diversity Task Force, now known as Hockey Is For Everyone, for which he is the League's diversity ambassador.

He was the player who opened hockey up, who endured the difficulty of being the first and the only black player over his 45 games in the NHL, and who spent years after crisscrossing North America to let kids know that they too could play hockey, that they too could achieve their goals, that they too could be who and what they wanted.

© Brian Babineau/Getty Images

The breaking of the barrier was historic and hugely significant, though the second black player, Mike Marson, would not join the NHL until the 1974-75 season, with the Washington Capitals. But it is what he has done since that continues to resonate.

"When you get up in the morning, you look at the mirror, you don't see a brown man or a black man, you just see a man," said O'Ree, 83. "I think that this is the thing that I try to get across to these boys and girls. Feeling good about yourself and liking yourself and believe in yourself.

"Being proud of who you are."

That message has landed.

"It's worked," said Bryant McBride, the NHL's vice president for business development from 1992-2000, who brought O'Ree back to the NHL. "It's helped generations of players and families. Willie has truly had generational impact. I really believe that. Because there's all kinds of boys, girls, kids, that realize, 'I can do this.' Hockey is one-tenth of it. It's about every other thing that they might try."

\\\\

It was as if Jackie Robinson had stepped out of history, out of the books and lessons and movies and into their lives. It was as if he adjusted their batting stances and straightened their uniforms and asked them questions about themselves, a mythical figure made real.

It has been 46 years since Robinson died, long enough that the next generation has only known him as an idea, as the man who broke Major League Baseball's color barrier, rather than as a flesh-and-blood human. Long enough for a sense of his actual being, while not his place in history, to pale.

O'Ree, meanwhile, is as real as anything. He is the one leaning over to tighten a kid's skates, asking, "Too loose? Too tight? Just right?" He is the one asking kids' names and remembering them. He is the one requesting the reports on racial incidents in the United States and Canada, learning about the situation, and calling, explaining how this happened to him too.

"Whoa," Syndey Kinder remembered thinking when she met O'Ree and dropped the puck with him in Boston in 2008 on the 50th anniversary of O'Ree's debut. "This guy exists in my time."

There he was, a piece of history in her life.

"You hear about these great people in history and you never get to meet these great people in history," said Kinder, who became the first graduate of the New York program Ice Hockey in Harlem to play college hockey, at Manhattanville College. "You hear about their impact on your life and in history, but you don't get to feel it, you don't get to see it, and you don't get to experience it.

"You live through these stories that your grandparents tell you. Whereas now, it's my story."

When O'Ree was brought back to the NHL, the point was for him to make an impact, to open the League and the sport up to those who might not have considered it, to allow those kids to see the possibilities.

In the 23 years since, the influence has been immeasurable.

Kinder is "one of thousands of kids who has that special relationship with Willie," as McBride put it.

One of thousands who feel honored and respected and touched when he actually remembers them on a second meeting, when he takes the time to get to know them, as Robinson once did for him.

He is the living embodiment of setting goals and reaching them, something he emphasizes in his well-practiced speeches and directives to the hockey players he sees throughout the year. As he says, over and over again, "If you think you can, you can. If you think you can't, you're right."

Long after he retired in 1979, he wanted to return to hockey, to give back to the game. He found his way back, made the impact that he always wanted to make. And now he joins the Hockey Hall of Fame.

"It put in perspective that people like me, people from my neighborhood, we can go other places than just around the corner," Kinder said. "There's so much more for us."

\\\\

Malik Garvin did everything he was supposed to do, as a high-achieving, motivated kid. He started playing hockey at 3 years old, made all-star games. He played NCAA Division III hockey and graduated from Western New England University with a degree in accounting and finance. He got a job on Wall Street. He transitioned to a wealth management firm in the New York suburbs.

He found something missing.

"I was like, I need to do more," the 26-year-old said. "I need to make a bigger impact on the world."

This past summer, Garvin left that wealth management firm and took a job as a program coordinator at Bronx Lacrosse, a New York organization that aims to empower kids through education and lacrosse, much like Ice Hockey in Harlem did for him.

Working through a public school in the Bronx, Garvin is aiming to push education with a nontraditional, generally nondiverse sport.

"I want them to have hope," Garvin said. "Basically, I held up my life story and others like mine and let them know there's more out there, even though they don't come from much."

That is the legacy of O'Ree.

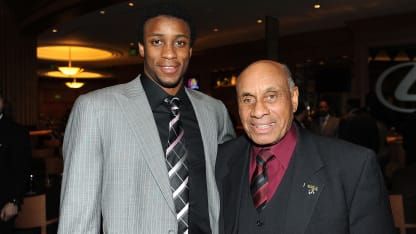

© Andrew D. Bernstein/Getty Images

Garvin met O'Ree a handful of times, including at the Willie O'Ree All-Star Game in Minnesota when he was 10 or 11, as well as at events for Ice Hockey in Harlem, one of the programs that O'Ree has championed.

"When I was growing up there wasn't Wayne Simmonds and P.K. Subban, it was just Willie O'Ree," Garvin said. "It was like Willie O'Ree, Willie O'Ree, Willie O'Ree. He was still the only big name for black hockey players in the early '90s. That was what everyone from our [area] held on to.

"You could be Willie O'Ree. He was the first black hockey player. You can be the next black hockey player."

\\\\

When Simmonds met O'Ree, he was speechless.

The Philadelphia Flyers forward couldn't remember all the questions he had, all the things he had planned to say. The moment makes him understand what it's like for the little kids who come up to him, and can barely get a word out, their parents dumbfounded at their normally chatty kids who are suddenly so silent.

"I was just star-struck and just stared at him," Simmonds said. "I knew I had a bunch of questions I wanted to ask him, but nothing really came out. It was like being a little kid."

And Simmonds had already made the NHL at the time; he was a rookie with the Los Angeles Kings.

The two have developed a relationship since, and Simmonds has been able to ask everything he wants as they have grown closer. That mere fact still seems to overwhelm Simmonds, who calls O'Ree a huge influence in his life.

"When I was 6 years old, that's when I started playing hockey and he was one of the first players my parents introduced me to, just obviously part of our culture," Simmonds said. "Just letting me know if this was my dream and I really wanted to do it, this was the man to look up to. He played a big part in me wanting to play in the NHL and allowing me to actually get to the NHL."

\\\\

O'Ree's path was far from easy. He made the NHL after losing the sight in his right eye after being hit by a puck. He was tremendously talented, tremendously fast, but he lasted two seasons in the NHL, though he did have a 21-year career as a player.

He could have fought every time he took the ice, he said. There were slurs and taunts and insults. There were threats. There was discomfort, and a message from his older brother that he couldn't change other people. He could only hold tight to the game he loved and prove that he belonged on the ice.

Video Player is loading.

Current Time 0:00

/

Duration 0:00

Loaded: 0%

0:00

Stream Type LIVE

Remaining Time -0:00

1x

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

Bettman, O'Ree at Museum of African American History

Which is why he now calls just about every single family that has experienced a racial incident on the ice in the United States and Canada. He calls the parents, talks to them, and later calls the kids, as he did for Taylor LeBlanc, who hails from O'Ree's birthplace, Fredericton, New Brunswick. Taylor then passed along O'Ree's message to his younger brothers.

"The older one passed on the wisdom to the next one, who then passed it on to the younger one," said Brenda Samson, a friend of O'Ree's who helped start the public push for O'Ree to join the Hall of Fame. "I often say we can never know the far reaches of Willie O'Ree's positive influence."

These are the moments that make up O'Ree's body of work, that make him into a builder of the game, a builder of young players, of young men and women, long after he left his playing days behind.

"I never thought he would be in there as a player. I always thought Willie would be a builder," said former NHL player and current broadcaster Anson Carter. "Willie spent countless air miles, countless hours, flying around the country, talking to kids, reaching out. Telling kids about how great it is to play hockey. Influencing these kids, influencing kids off the ice and showing them how hockey can help with their education and different life skills.

"If that's not a builder, I don't know what is."

Simmonds said, "Whether it's hockey or whether it's being an astronaut or whether it's being a schoolteacher, a brain surgeon, whatever it is, I think it just goes to show you that if you put your mind to something and you work as hard as you possibly can and you're determined, you don't let anyone tell you no, you can definitely do it. He's a big part of that in allowing kids [to dream]."

That is his legacy. Forty-five games in the NHL, one barrier broken, and an impact that will last for generations.

"People in hockey know who Willie O'Ree is," McBride said. "They don't know who he's impacted. This is the building part. This is why he's in the Hall of Fame."