MONTREAL -- It was four years ago, nearly 60 years after the supposed fact, and with a giant grin Pierre Pilote wanted to clear something up once and for all.

The legendary Chicago Black Hawks defenseman never knocked out both Maurice and Henri Richard, the Montreal Canadiens' iconic brothers, in a single 1950s NHL fight.

The legend of this bare-knuckled feat has lived a healthy life in biographies and stories; it's even been boasted, as Pilote recalled during a 2013 appearance at a Montreal collectible show, on the back of one of his hockey cards.

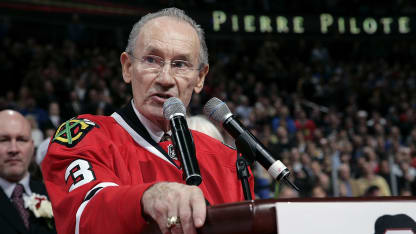

Former Black Hawks captain Pilote dies at 85

Hockey Hall of Fame defenseman won Norris Trophy three times, Stanley Cup in 1961

© B Bennett/Getty Images

By

Dave Stubbs @davestubbs.bsky.social

NHL.com Columnist

So Pilote, inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1975, simply let folks believe what they wanted to believe, shrugging his shoulders for six decades as the myth grew to epic proportions.

Pilote died at age 85 Saturday night in a hospital in Barrie, Ontario, after a months-long battle with cancer. At his bedside were his children: daughters Denise and Renée, and sons Pierre Jr. and David.

\[Commissioner Bettman releases statement on passing of Pilote\]

The story of his double-knockout of the Richard brothers will, and probably should, live forever, a story bigger than life for a defenseman who always played several sizes larger than his 5-foot-10, 175-pound frame.

In fact, Pilote once scored a double knockout, but it came in the early 1950s in the minors. Then with Buffalo in the American Hockey League, he iced Pittsburgh's Ray Timgren and Elliot Chorley, the Hornets pair not quite the pedigree of the Canadiens' Richard brothers.

This isn't to say that Pilote didn't have his tussles with Rocket and Henri during his career, 14 seasons from 1955-69 that saw the eight-time All-Star win the Stanley Cup in 1961 and three consecutive Norris trophies from 1963-65 as the NHL's best defenseman.

"I had a brawl with Henri," Pilote recalled almost wistfully when he settled back to consider his career. "Rocket jumped in to help his brother and my buddy, Harry Watson, came in and pulled Rocket off me. But I don't think anyone ever knocked Henri down, much less knocked him out. He's a tough little guy."

That was one story in a dozen that Pilote joyfully related in a nostalgic hour-long talk, the Black Hawks legend breezing through Montreal for a quick visit to sign autographs. The last time the native of Jonquiere, Quebec, had been here was nearly 15 months earlier, in transit to his hometown in the Saguenay region for the unveiling of a statue of himself at the local sports center.

Until his failing health had kept him at home in Wyevale, Ontario, Pilote had remained a gigantically popular figure any time he visited the Windy City, honored with fellow alumni in the spring of 2010 when the Blackhawks paraded their first Stanley Cup since Pilote's title almost a half-century earlier.

"In '61, we had a small parade from one hotel to another, then went to the Bismarck [hotel] for a little party," Pilote said. "When I rode in the parade in 2010, it was crazy. I felt like I'd won the Cup again."

He had enjoyed a day with the trophy on Aug. 28, 2005, 30 years to the day of his Hall of Fame induction. It was a grand day in Wyevale, in the Georgian Bay region, when Pilote shared the Cup with his wife, Anne, four children, many of his grandchildren and an adoring town that he would call home for the last two decades of his life.

Pilote lost Anne, his kindred spirit, in May 2012 after 58 years of marriage. As Anne took ill, he began work on an autobiography, titled "Heart of the Blackhawks," co-authored by Waxy Gregoire and David Dupuis and published in October 2013. The book was written in part as a tribute to her, putting between covers his almost unreal life before, during and after hockey.

© Bill Smith/Getty Images

In March 2013, Pilote was celebrated at United Center with his own bobblehead doll. That his captain's "C" appeared on the wrong side of his jersey, on the right, not over the heart, was of no concern.

"It is what it is," Pilote joked, channeling the phrase uttered by every modern NHL player. "They took a photo from my first year as captain to make the bobblehead. Gunzo (Walter Humeniuk), our trainer, didn't know which darn side to sew the 'C.'

"But," he added, laughing again, "that never affected my game!"

Indeed, Pilote was not the fearsome physical specimen of, say, hulking defense partner Elmer "Moose" Vasko. But he could lay on the body with the best of them and his rushing style, which he patterned after Canadiens great Doug Harvey, would later be the template for the games of future Hall of Famers Larry Robinson and Denis Potvin.

"I always believed that if I had the puck, the other team didn't have it," Pilote once said. "My first instinct was always playing forward. I'm what you call 'Mr. Xerox' -- I copy. If it's good for you, it's mine. My hero was Doug Harvey. I picked up tricks from him and from other guys and that's how I learned."

His nasty streak was self-taught. Pilote was a tough cuss, seven times finishing in the NHL's top 10 for penalty minutes, leading the League in Chicago's championship season.

He recalled once being drilled into the Montreal Forum glass by the Canadiens' Bob Turner, having his helmetless skull split open for 20 stitches while he successfully fed teammate Bobby Hull for a goal.

"I had the stitches taken out about a week later and then in Detroit a guy creased me right over the head with his stick and opened it up again," Pilote remembered. "I went into the clinic and the doctor said, 'We'll have to re-stitch that. I'll give you a shot of Novocain to kill the pain.'

"He waited a bit then with his scissors he straightened out the edges before sewing me back up. When the shot wore off, my goodness, I thought my head was going to explode. Little things like that happened in my career," he said, chortling at this thigh-slapper.

Pilote vividly recalled the triple overtime in Game 3 of the 1961 Semifinal vs. the Canadiens, ultimately decided by Chicago's Murray Balfour. Players of the day weren't big on in-game hydration and Pilote remembered Black Hawks general manager Tommy Ivan slipping his squad, on the bench, brandy-soaked sugar cubes as the game wore on.

The 1961 championship forever was his career highlight, a postseason when he tied Detroit's Gordie Howe with a League-leading 15 points (three goals, 12 assists). He'd almost surely have been named the Stanley Cup Playoffs' most valuable player had the Conn Smythe Trophy not been four years from creation.

"I didn't worry about losing or winning. I had to just play my best," Pilote said. "I was relaxed and had a lot of confidence. It seemed like I could do anything, like I could see plays before they happened."

© B Bennett/Getty Images

Thirteen of Pilote's 14 seasons were spent with Chicago, his final in Toronto after a May 1968 trade for Jim Pappin. If he bristled then at how the deal was executed, learning of it from a reporter, it would prove to be a splendid turn in his life post-retirement.

Pilote got into business in a big way when he hung up his skates. He ran a car dealership, was a sports advisor for Sears, represented Bell, operated laundromats, founded a luggage-and-tote company, bought and ran a hobby farm in Milton, Ontario, breeding Angus cattle, worked in Tim Hortons management then bought a store and raised German short-hair pointers.

"And I learned to play golf in my spare time," he said, laughing once more.

Pilote was 10 pounds under his playing weight when we sat to talk, "though I could get fat if I wanted to." He still made occasional card-show stops, amazed at the lineups for his signature that never end.

"I've been recycled a lot since the Blackhawks retired my No. 3," he said, his sweater and that of the late Keith Magnuson pulled to the United Center rafters in 2008.

He marveled at today's NHL and thought highly of Nashville Predators defenseman P.K. Subban, whom he saw as the inventive rusher that he worked to be.

And that most of today's players are multimillionaires before they're 30?

"Everything changes and I'm all for it," said Pilote, who figured his salary topped out at $45,000. "I don't feel I didn't get all of these goodies. My goodies were much better than the guys who played before me.

"You know, I look at my life and it's just amazing. I don't know if I've done the right things, been lucky, or a little of both."