Bobby Hull signs autographs for Chicago Black Hawks fans in the 1960s.

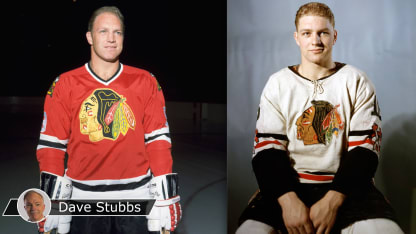

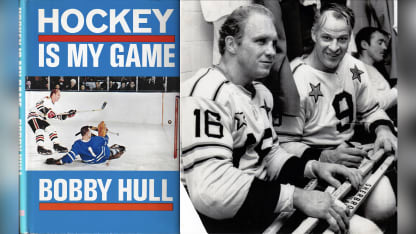

After 15 seasons with the Blackhawks from 1957-72, he bolted for the Winnipeg Jets of the fledgling WHA, playing seven seasons there before wrapping up his career with 27 games in 1979-80 with the Jets and Hartford Whalers.

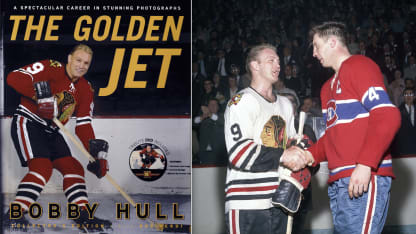

He was a lock for Hall of Fame enshrinement to everyone but himself, and when his moment came in 1983, he went in along with his dear friend Stan Mikita and Canadiens goalie Ken Dryden.

"At the time, I was at loggerheads with the NHL for having gone to the WHA," Hull said. "I knew that the Hall was pretty well about putting NHLers in there. But it came as a great enjoyment for me that after all the years I'd played, 23 professionally, my friend Stan and I would be honored together. I was, and I am, very, very proud to be known as a Hall of Famer."

Hull would almost burst with fatherly pride when his son, Brett, was enshrined in 2009, after he had 1,391 points (741 goals, 650 assists) for five teams during 19 seasons.