“So, partway through the summer I called Cail because he said, ‘Just keep me in the loop on what your plans are,’” Carbery said. “So, I called him and said, ‘I think I’m going to play one more season. I looked around at some stuff and I would like to have another year to maybe meet some people in Charleston and play at the same time.’”

MacLean had a different idea. He was looking for an assistant and saw Carbery as a perfect fit.

“The idea that he was there for his team’s benefit, that was the way he approached the game,” MacLean. “He also had the drive to do the little things that teams need to do to win. So, yeah, he was a great candidate.”

Carbery was surprised, though, when MacLean asked, “Have you ever considered coaching?”

“I said, ‘I never thought about it. No,’” Carbery said. “And I’ll never forget this, and he gives me a hard time about it, but it is true. I go, ‘I’d really like to play another season.’ And he goes, ‘Well, I didn’t ask you to play another season.’”

Carbery, who was 28 at the time, realized then that his playing days were probably over. So, he asked MacLean what the assistant job entailed. MacLean outlined what Carbery’s responsibilities would be. The hours would be long, and the pay minimal -- more on that later.

“So, I go home and talk to my wife, and I was like, ‘That is not good,’” Carbery said. “But then I started to think about the other things I could do that would potentially help transition into the financial world or whatever. So, I took the job and immediately when I started coaching, I loved it even more so than playing.

“Just going on the ice and breaking film down and doing pre-scouts and helping players sort of maximize their talents and abilities and trying to share information that could maybe help them a little bit in games or in their careers, I fell in love with it right away.”

After Carbery’s first season as an assistant, MacLean left for an assistant position with Abbotsford, leaving the Stingrays job to Carbery.

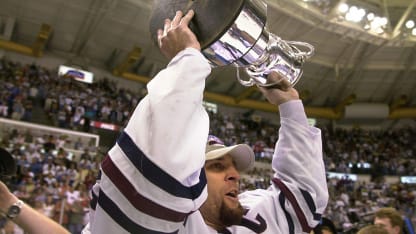

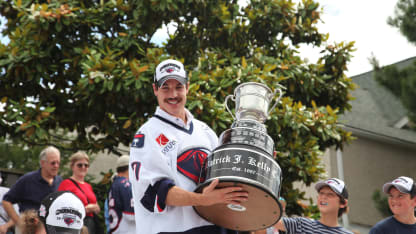

During Carbery’s five seasons in charge, South Carolina went 207-115-38, including an ECHL record 23-game winning streak from Feb. 7-March 27, 2015, finished first in its division twice, reached the conference finals twice and advanced to the 2015 Kelly Cup finals before losing to Allen in seven games.

“Spencer, he was just determined,” Concannon said. “He was detailed. I’ve never seen anyone work as hard as Spencer did back in the day and I think those qualities and attributes spread over to Ryan.”

Carbery, who won the John Brophy Award as the ECHL’s coach of the year in 2013-14, left South Carolina following the 2015-16 season to become the coach of Saginaw in the Ontario Hockey League. From there, he went to the AHL with Providence as an assistant for one season (2017-18) and the Capitals affiliate in Hershey as coach for three seasons (2018-2021) before taking an NHL assistant job for two seasons (2021-2023) with the Toronto Maple Leafs.

The Capitals hired Carbery in 2023 after missing the playoffs for the first time since 2014. Washington went 40-31-11 in his first season to earn the second wild card from the Eastern Conference.

He hopes to build on that this season but never forgets where and with whom he started.

“I felt like I was getting a master class every day from being around ‘Bedsie’ and Cail and Ryan,” he said. “So, you’re just becoming a better coach each and every day by being able to steal ideas. ‘That’s a great idea. Wow.’ And I think where it starts is quality, quality people.”

* * *

Unlike Bednar and Carbery, Warsofsky knew his calling was behind the bench. Unlikely to make the NHL as a 5-foot-9 defenseman, he’d begun thinking about going into coaching before the 2012 hip surgery that ended his brief professional playing career, which included a stint with Turnhout in the Belgian Hockey League in 2011-12.

Warsofsky was 24 when he landed his first coaching job as an assistant at his alma mater, Division III Curry College in Milton, Massachusetts, in 2012. After one season at Curry, he heard the Stingrays had an opening for an assistant and emailed Concannon on a whim.

“It was just more of a feeler,” Warsofsky said, “and I remember my phone ringing and it was a Charleston number and it was 10 minutes after I sent the email.”

As Massachusetts natives, Warsofsky and Concannon had some mutual friends, but didn’t know each other directly. Still, Concannon called Warsofsky immediately and decided to show his resume to Carbery.

“Robby being a Boston guy says, ‘I think you should take a look at this one. I just got his resume today, Ryan Warsofsky,’” Carbery said. “And two of his three references are Mike Sullivan and Ray Bourque.”

Warsofsky was neighbors with Sullivan, the Pittsburgh Penguins coach, in Marshfield, Massachusetts. In fact, Sullivan’s parents are Warsofsky’s godparents. Warsofsky is also friends with Bourque’s sons, Chris and Ryan, and played two years at Cushing Academy (2005-07) in Ashburnham, Massachusetts, when the Hockey Hall of Fame defenseman was an assistant coach there.

“So, I’m like, ‘There’s no way I’m not calling Ray Bourque,’” Carbery said, laughing. “So, I pick up the phone and call Ray Bourque and go, ‘Hey Ray, you’re a reference on Ryan Warsofsky’s resume.’”

Having Sullivan and Bourque as references helped Warsofsky get his foot in the door, and he took over from there, convincing Carbery and Concannon he was the right man for the job.