When Kyle Connor was 13 or 14, his coach told him he needed to work on his shot, so he set up a net, a slab of artificial ice and a bucket of pucks in the garage. He'd put on tunes -- rock, country or rap, depending on the mood -- and shoot, shoot, shoot.

Connor makes 2022 NHL All-Star Game after work ethic pays off with Jets

Forward tied for seventh in League in goals, 'determined to make himself a great player'

"That garage got destroyed," he said with a laugh.

Now the Winnipeg Jets forward is headed to the 2022 Honda NHL All-Star Game at T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas on Feb. 5 (3 p.m. ET; ABC, SN, TVAS, NHL LIVE) as one of the best goal-scorers in the League.

Connor has scored 20 goals this season, tied with Tomas Hertl of the San Jose Sharks and Brad Marchand of the Boston Bruins for seventh in the NHL, including 17 at even strength, tied with Hertl for second behind Alex Ovechkin (18) of the Washington Capitals.

WPG@DET: Connor scores SHG in 3rd period

Since 2017-18, his first full season in the NHL, Connor (149) is sixth in goals behind Ovechkin (197), Auston Matthews (184) of the Toronto Maple Leafs, Leon Draisaitl (175) and Connor McDavid (168) of the Edmonton Oilers and David Pastrnak (157) of the Bruins. He's fourth in even-strength goals (107) behind Matthews (136), Ovechkin (133) and McDavid (127).

"I mean, it's definitely something to look at and be like, 'All right, that's pretty cool,' but you know, I'm not retiring tomorrow," said the 25-year-old, who on Thursday was named to his first NHL All-Star Game. "I try to get better every single day. That's how I develop my skill set and why I think I've been successful since I got in the League."

Connor's journey hasn't been a straight line, but it all goes back to that garage mentality: Work hard to make the most of your talent. Love it so much it doesn't feel like work.

"He's always one of the hardest workers on the ice," said Detroit Red Wings goalie Alex Nedeljkovic, who played with and against Connor growing up and trains with him in the offseason. "He's always giving it 100 percent, and it's no surprise. I wasn't really surprised when I [saw] him putting up 25, 30 goals a year. I think he's honestly pretty underrated throughout the League as a goal-scorer."

Connor (right) played one season with future NHL goalie Alex Nedeljkovic (back), who now trains with him in the offseason and called him "always one of the hardest workers on the ice."

* * * * *

When Connor was little, his family lived in New Baltimore, Michigan. He'd Rollerblade in the cul-de-sac and play hockey in the unfinished basement.

Later, his family moved to a house on Blue Cloud Drive in Shelby Township, Michigan, perfect for a kid with his head in the clouds and a drive to play in the NHL. The lot was big enough for his father, Joe, to build a backyard rink, so he could come home from practice, turn on the lights and skate for hours outdoors. Sometimes he'd shoot on a cousin who played goalie.

"He was always busy doing stuff," said his mother, Kathy. "He was not a kid that would sit around on a Saturday afternoon."

His mother said he would shoot 100 pucks a day when he started working in the garage, breaking a window once, leaving marks on the concrete and cinderblocks. Joe Smaza, his coach then, said it was probably more like 500 pucks a day -- the first 100 as hard as possible to build strong hands, the next 100 to pick one upper corner, the next 100 to pick the other upper corner and so on, each shot with a purpose.

"I honestly felt that helped a lot with just having a quick release and just muscle memory and being able to shoot the puck like that," Connor said. "It's something where it's fun as well."

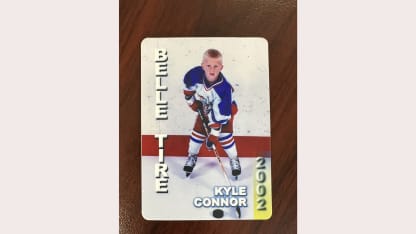

Connor played for Belle Tire growing up in suburban Detroit until he joined Youngstown of the USHL.

Connor also started go to goalie camps as a shooter, learning the goalies' tricks and how to outsmart them.

"It's almost like a 1-on-1 chess game with the goalie at times, and I love that little competition," Connor said. "It's fun."

Connor wasn't big, and he had to find a way to separate himself from the competition playing for Belle Tire with future NHL players like Dylan Larkin and Zach Werenski against teams with future NHL players like McDavid and Robby Fabbri.

"Kyle's always done what he's doing now, which is just outwork the guy across from you and get pucks on net and play with a high level of speed and skill and agility," Smaza said. "That's what we always knew was going to make him successful."

Connor (left side) played with future NHLers Dylan Larkin (front) and Zach Werenski (back right) in the Quebec International Pee-Wee Hockey Tournament.

Connor did not make the USA Hockey National Team Development Program at first, but he played for Youngstown of the United States Hockey League as a high school sophomore in 2012-13. After a slow start against older competition, he ended up scoring 41 points (17 goals, 24 assists) in 62 games.

The NTDP offered him a spot afterward, but he stayed in Youngstown.

"Everybody's path is different," Connor said. "If you don't make one team, it could be a blessing in disguise. I kind of took it as an opportunity."

Connor scored 74 points (31 goals, 43 assists) in 56 games in 2013-14, a Youngstown record, and 80 points (34 goals, 46 assists) in 56 games in 2014-15, leading the league. He was named USHL Player of the Year.

The coaches had to kick him off the ice after practices.

"He was always out there," said Youngstown coach Brad Patterson, an assistant then. "It wasn't work to him. He was working on his craft, but at the same time, he had the biggest smile on his face when he did it.

"That's a great example for us and our young guys internally here. There's a reason these guys get to their spots. Obviously, they're very gifted, but they're also very driven, and they're relentless in becoming better at their craft."

Red Berenson, Connor's coach at the University of Michigan and a member of the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame, said much the same thing.

"All these good players, they've worked for it," Berenson said. "You read about Connor McDavid and his background. He did the same thing. He was shooting and playing hockey in the driveway when everybody else was playing video games. He was just determined to make himself a great player."

Connor played one season at Michigan, as the left wing on the "CCM Line" with future NHLers J.T. Compher and Tyler Motte in 2015-16. He scored 71 points (35 goals, 36 assists) in 38 games.

He scored eight points more than the next closest player (Compher) and three more goals than the next closest player (Motte) in NCAA Division I. Berenson called him hands-down the best player that season, but he finished second to another future NHL player, forward Jimmy Vesey, in the voting for the Hobey Baker Award, given to the top men's player in Division I ice hockey. Vesey was a senior who scored 46 points (24 goals, 22 assists) in 33 games for Harvard.

"He'd go down on a bad-angle scoring chance and score, whereas nine times out of 10 nobody else could," Berenson said of Connor. "He was just one of those players. And he knew how to get open. He anticipated well. He kind of knew where the puck might go, and he got open, and when it came to him, he was gone. And he's doing the same thing now in the NHL."

* * * * *

Connor did not succeed in the NHL at first.

After making the Jets out of training camp in 2016-17, he scored four points (one goal, three assists) in his first 19 games and was sent to Manitoba of the American Hockey League.

"I think it was for the best," he said.

As much as Connor wanted to play in the NHL, he needed to adjust to the pro game. He didn't score right away in the AHL, either, but ended up with 44 points (25 goals, 19 assists) in 52 games for Manitoba. He also scored a goal when he got a chance to play one game for Winnipeg late in the season.

He didn't make the Jets out of training camp in 2017-18. But he scored five points (three goals, two assists) in four games for Manitoba, then got called up because of an injury to forward Mathieu Perreault and got a shot on a line with center Mark Scheifele and right wing Blake Wheeler. He scored in his first game.

"You've got to take advantage when you have an opportunity," he said.

Connor led rookies in goals (31), was fourth in points (57) and finished fourth in voting for the Calder Trophy, awarded to the NHL rookie of the year. But Paul Maurice, who coached the Jets then, often brought up a game when Connor worked hard but didn't score a point: a 3-2 win at the Carolina Hurricanes on March 4, 2018.

"That was the message we wanted to give him -- that all you have to do is that, and everything is going to come for you," Maurice said. "We wanted Kyle to be harder on the puck and harder to the puck and contain it and control it more with his skills. That was why he didn't start [in Winnipeg that season]. He just worked at it and worked on it."

Connor scored 66 points (34 goals, 32 assists) in 82 games in 2018-19, setting NHL career highs.

He set NHL career highs again in points (73), goals (38) and assists (35) in 71 games in 2019-20 despite the schedule being shortened due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Top 10 Kyle Connor plays from 2019-20

He scored 50 points (26 goals, 24 assists) in 56 games last season amid another shortened schedule, plus a triple-overtime goal to finish a sweep of the Oilers in Game 4 of the Stanley Cup First Round.

This season, he's raising the bar even higher, with the best rates of goals per game (0.59), assists per game (0.50) and points per game (1.09) of his NHL career.

"He's continued to improve at the NHL level," Berenson said. "He can score just about any way you want, whether he's standing in front of the net tipping in pucks, or he's on his off wing where he rips it and one times it, or he gets on his on wing and his release is comparable to Matthews' release, because he gets rid of the puck so quick. He surprises a goalie, and he puts it where he wants it.

"It's amazing. I've seen him play a lot. I've seen him score a lot of goals in the NHL. I'm really impressed with the way he's continued to develop."

The other amazing thing? Connor has 29 takeaways, tied with Aleksander Barkov of the Florida Panthers for 21st in the NHL and is killing penalties too. He's 6-1, 182 pounds.

"He works harder at the whole game now," Berenson said. "You watch him backcheck, and you watch him steal the puck from players. … He wins battles on loose pucks against guys that are a lot bigger and stronger than he is. He's quicker and smarter, and he's good along the boards and in the corners when there's scrums, and he finds a way of getting the puck, and away he goes."

Again, it all goes back to that garage mentality: Work hard to make the most of your talent. Love it so much it doesn't feel like work.

And keep doing it and doing it and doing it.

Jets goalie Connor Hellebuyck is also from suburban Detroit and goes home in the offseason.

"He always has two days a week where he just does goalie drills, and he needs shooters," Connor said. "You know those goalie drills. It can be a lot of shots, and especially Hellebuyck likes it tough. It gets us better as shooters as well."

Connor laughed.

"I always love going out there and trying to pick apart some goalies," he said.

NHL.com staff writer Tim Campbell contributed to this report