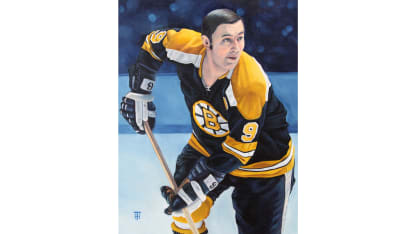

"I played most of my career at 220 pounds, one of the heaviest players on the ice," Bucyk told Chris McDonnell in "For the Love of Hockey." "I threw my weight around and always played a physical game. The other players respected me because they knew if they had their head down, I'd hit them pretty hard. I just tried to stay out of the penalty box."

His physical character fit perfectly into the club that Boston began assembling in the mid-'60s. Bucyk, the Bruins captain for the 1966-67 season (and again from 1973-77), had to acclimate Orr, the teenage sensation who Bucyk made sure felt included from the first day of training camp.

"Johnny was a great help to me making the transition from junior hockey to the pros," Orr wrote in his autobiography. "He came to work every day and set the standard with his level of play. He always set the bar high for us, and it made you want to follow suit and set your own example for others. There can be no doubt that his leadership was a key part of the success the Bruins would enjoy in the years that followed."

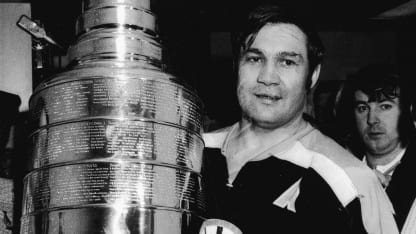

Trades and call-ups helped build Boston into a stronger club that could play any style and win. And when new coach Harry Sinden teamed Bucyk with center Fred Stanfield and right wing John McKenzie in 1967, he created what many called the NHL's best second line, playing behind Esposito, Ken Hodge and Ron Murphy (who gave way to Wayne Cashman).

"We had three [scoring] lines, we had a great penalty killing unit, we had very strong defense, we had a very physical team, we had the fighters, we had the finesse players, we had such great team spirit, the players just stuck together," Bucyk said on the TV series "Hockey's Greatest Legends," as he ticked off the club's attributes. "We were called the Big Bad Bruins because we were big and bad and tough."