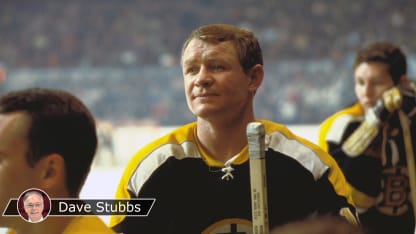

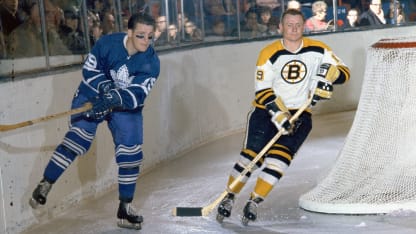

Johnny McKenzie, a forward who was a key cog on the Boston Bruins' Stanley Cup championship teams in 1970 and 1972, died Friday at his Boston-area home after a lengthy illness. He was 80.

McKenzie, nicknamed "Pie," was born Dec. 12, 1937 in High River, Alberta, about 40 miles south of Calgary. He was a rodeo competitor early in his life, earning the nicknames "Cowboy" and "Bronco." Those came before "Pie Face," for his apparent resemblance to a Canadian candy bar's cartoon illustration, which would be shortened to "Pie" for the shape of his face (or his posterior, according to old friend and Bruins teammate Phil Esposito).

McKenzie, two-time Cup winner with Bruins, dies at 80

Forward played on Boston's championship teams in 1970, 1972

© Denis Brodeur/Getty Images

© Denis Brodeur/Getty Images

© Steve Babineau/Getty Images

© Elsa/Getty Images