The rink arrived when Kevin Stevens was seven.

He was a mite and, suddenly, there was Hobomock Arenas, on Hobomock Street in Pembroke, Massachusetts, a rink with two sheets of ice and all the promise in the world. And even though Stevens was a multi-sport kid, a kid from an all-American family whose first love was always baseball, his aunt issued him a challenge for his time on skates.

One dollar per goal.

“That pretty much bankrupted her,” said Kelli Wilson, Stevens’ sister. “She couldn’t do it anymore because he was getting three, four, five, six goals a game.”

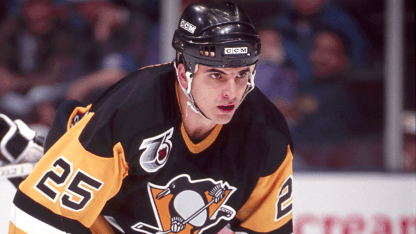

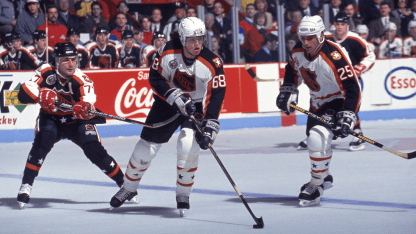

It was a scoring touch that was there from the start, a natural ability that combined with Stevens’ size to create the model of a power forward, a player who bulled through the NHL to the tune of 726 points (329 goals, 397 assists) in 874 games for five teams, most notably the Pittsburgh Penguins, with whom he won the Stanley Cup twice. It’s a talent and drive which has now earned him induction into the United States Hockey Hall of Fame, set for Dec. 4 in Pittsburgh.

It was everything he could have hoped for, wanted.

It was a dream. Until it wasn’t.

Stevens' career was derailed on May 14, 1993, when he headed down the ice, hunting a puck set for an icing in Game 7 of the Eastern Conference Division Finals against the New York Islanders. Rich Pilon touched it and Stevens careened into him, the impact sending Stevens flying, his head hitting Pilon’s shield and knocking him out.

His face met the ice, crushing his nose and orbital bone and forehead so much that it had to be entirely reconstructed by surgeons.

“I can’t even watch it,” Wilson said, of videos of the moment.

Nothing would ever be the same.

But after it all, after the recovery and the descent into drug addiction, after the arrest and the jail time and another kind of recovery, Stevens is on the other side, in a place where he is helping others and content with his life, a place where he’s seeing his contributions on the ice be remembered and honored, even 22 years after he last played in the NHL.

“When he got into the Hall, he was so humble,” Wilson said. “He was like, 'Kell, I never saw this coming.' And I said, ‘Why not, Kev? You were one of the best American-born left wings, if not the best, in the country, in the world.’”