Twenty years have gone by, and the sticker remains, a reminder tucked behind the left ear. The sticker, a crown with the name "Ace" arching over it and Mark underneath, has adorned the helmets of hundreds of Los Angeles Kings players, those who remember exactly where they were on Sept. 11, 2001, and those, like

Quinton Byfield

, who weren't yet born on that day.

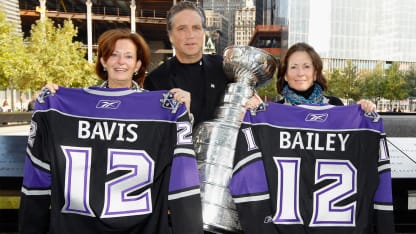

Kings continue to honor Bailey, Bavis on 20-year anniversary of 9/11

Legacies of director of scouting, amateur scout, who died in terrorist attacks, will never be forgotten

It's that sticker, the quiet black-and-white reminder of lives now 20 years gone, that causes Mike Bavis' voice to get husky and thick. It's the idea that, even after all this time, no one in the Kings organization, no one in hockey, has forgotten Ace Bailey or Mark Bavis, two victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks that claimed the lives of 2,977 people.

"When they say, 'Never forget,' a lot of those people with the Kings weren't even there then," said Mike Bavis, Mark's twin brother.

And yet, the Kings have ensured that their memory is ever-present.

"It allows us to be able to tell the story," said Daryl Evans, the Kings radio commentator. "We all move on, but we never forget."

Bailey, then the director of scouting for the Kings, and Bavis, an amateur scout with the team, each was aboard United Airlines Flight 175 from Boston to Los Angeles when hijackers took over the airplane and flew it into the south tower of the World Trade Center in New York.

Garnet "Ace" Bailey was 53. Mark Bavis was 31.

\\\\

Bailey -- full of light and life, magnetic -- was beloved with the Kings, and across hockey. He earned seven Stanley Cup rings, two as a player with the Boston Bruins, five more as a scout for the Edmonton Oilers. He was a mentor and roommate to Wayne Gretzky and the son of NHL Hall of Fame forward Irvine "Ace" Bailey. He played 10 seasons in the NHL (and one in the World Hockey Association) for the Bruins, Detroit Red Wings, St. Louis Blues, Washington Capitals and Oilers.

"He was a character," Gretzky told NHL Network Sirius XM for their podcast "9/11 and sports: 20 years later." "He really didn't have any enemies. Him and I became best friends. He was my roommate in the WHA. He was a stepdad to me, he was like a big brother, everything all in one. At times he'd be my hardest critic. He would put me in my place."

As Jeff Moeller, who was Kings public relations director in 2001 and now is senior director of business communications and heritage, simply put it, "Ace was the best."

He was warm. He was welcoming. He made friends everywhere.

"Some people just have it. It's a gift. It might be his smile, his words, saying the right thing at the right time," Evans said. "He just captivated your attention when he was around. He just put a lot of energy into any room that he stepped into."

Bavis was younger, finding his footing in his hockey career after four years at Boston University, where he played alongside Mike, and three years in the American Hockey League and ECHL. He had come to the Kings a year earlier and already had demonstrated his eye for talent, advocating for two college players, David Steckel and Michael Cammalleri, who the Kings would select in the first and second round, respectively, of the 2001 NHL Draft, Bavis' only draft with the team.

The LA Kings remember Ace Bailey and Mark Bavis

Mark and Mike were part of the Bobby Orr generation in Boston, growing up in a big family with six older siblings, though they were the only kids in the family to play hockey. It was a game they would ride all the way to the coaching and professional ranks.

"It was always having a linemate, a teammate, someone to compete against, to compete with," said Mike Bavis, who was recruiting as an assistant coach for Boston University in Calgary on 9/11. "We were lucky.

"He was well-liked, he was a great teammate. He was a great friend to so many different people. For me, it's hard to describe. It was both competitive in how we competed athletically, but it's a special bond that twins have, especially ones that are together as often as we were."

The legacies of Bailey and Bavis have stretched long beyond that day, though. The Ace Bailey Children's Foundation built "Ace's Place" at Tufts Children's Hospital in Boston and made lives better for children in the neonatal intensive care unit and pediatric emergency room before closing its doors in November 2020. The Mark Bavis Leadership Foundation has raised more than $400,000 and gives college scholarships and grants to Massachusetts high school students.

The two families have become close, united in their shared loss, their shared grief, pulled together every year when the date swings around, bound by what Mike Bavis calls a "powerful connection."

That connection hasn't wavered through the years, growing stronger as the days have melted away, as two decades have elapsed since the tragedy brought them together. It feels like a long time and no time at all for those who knew the two men.

"You wonder where 20 years has gone," said Evans, who makes a point to visit the 9/11 memorial when he's in New York with the Kings. "It still seems like it was yesterday. I think a lot of that is because of the way that we honor them each and every day. They're always a part of [us] here in Los Angeles. I think that speaks to how special they were.

"Every day, they're around us. There's constant reminders."

There are the decals, the Kings mascot, Bailey -- named to honor a man for whom children's charities were a priority -- and the two awards that the Kings give out annually: The Mark Bavis Memorial Award for Best Newcomer and the Ace Bailey Memorial Award for Most Inspirational.

They're still talked about, still remembered, still mourned.

"I wrote things out last night," said Pete Demers, who was the Kings head athletic trainer in 2001, about what he wanted to share about Bavis and Bailey. "But I didn't realize how hard it was going to be to keep the tears from coming. It's just like it happened last night.

"We lost two of our wonderful men in our Kings family, in Mark Bavis and Ace Bailey, and so many more, 2,975, in this senseless tragedy."

\\\\

Bailey and Bavis took the flight together on their way back to Los Angeles as the Kings opened training camp. Bruce Boudreau, then coach of the Kings' American Hockey League affiliate in Manchester, New Hampshire, had been slated to fly with them but changed his ticket from Sept. 11 to Sept. 10 after being convinced by Kings coach Andy Murray over the weekend to return early for a coaches' dinner.

However, the price difference for the ticket switch was too much in Bailey's eyes, so he remained on the original flight.

"I remember the last thing, when he dropped me off at the house. I said, 'I'll see you Tuesday morning,'" Boudreau told the NHL Network Sirius XM podcast.

In Los Angeles, the first day of training camp was dawning on that day, full of anticipation.

And then suddenly, it wasn't.

"For a day that's usually buzzing very early, it was very quiet," Moeller said. "All the televisions were on. You're trying to conduct business as usual, but word started sprinkling around that Ace and Mark could -- this could be a discussion point. We knew they were flying that day. We knew they were flying from Boston. We knew that typically at that time we used United Airlines for travel."

The puzzle pieces were beginning to fit together in an unimaginable way.

Dave Taylor, who was then Los Angeles' general manager, tried their cell phones -- three, four, five times -- in the futile hope that they might pick up and end the nightmare. He wanted so badly to reach them, to disprove what Katherine Bailey had told him was true, that she had dropped her husband off at the airport, that he was on that flight.

"You're kind of hoping, always hoping, that they were OK somewhere," said Taylor, who would be given the job of breaking the news to the team and staff. "But at the end of the day, we finally found out they were on the plane and they had gone into the World Trade Center. It was terrible."

For them, 20 years have not dimmed the day. It still feels near, visceral, present.

"It gets pretty raw," Taylor said. "It's been 20 years now. It's hard to believe that that much time has gone by."

\\\\

Early that morning, around 5:30 a.m., Demers had taken a stationary bike out at the team's training facility in El Segundo, California, setting it on the patio in the sunshine. He knew Bailey and Bavis were set to arrive in Los Angeles around noon and thought Bailey would want to be out, in his favorite place, in the sunshine.

"Ace, he's a special person," Demers said. "Always friendly, happy, with a great sense of humor and a real warm smile. A great guy. He always had time for everybody and everyone. On that first day of camp, I wanted to make my friend happy upon his arrival."

As the news trickled out, as the fears welled up and were confirmed, as the day dragged on and the hope dimmed and vanished, the bike sat out there in the California sun, waiting, a sign affixed with tape.

"Reserved for Ace Bailey," it said.

The day, that terrible day, drew to a close. Everyone left. Demers knew he had to bring the bike back inside, untouched, unridden. He gathered his strength, asked his mother, who had died five years earlier, for her help, and he did what he had to do.

"I think it was the hardest day I ever had in my 41-year pro hockey career," Demers said. "And, by far, the hardest thing I've ever had to do in my life was to put Ace's bike back in the gym at the end of the day.

"It's something I'll never get over, I'll never forget, removing the sign 'Reserved for Ace Bailey' from the bike."