Bruins legend Hitchman deserves Hall recognition

Unsung great was dependable leader who excelled in the shadows

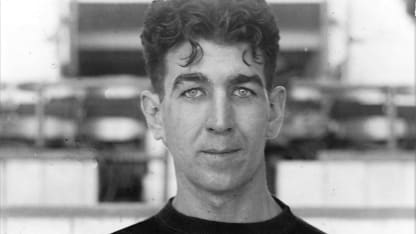

Lionel Hitchman played the last of his 417 NHL games 82 years ago Monday, his No. 3 Bruins jersey retired immediately after the home team's 3-1 loss to the Ottawa Senators at Boston Arena.

His would be the first of now 10 numbers the Bruins have retired and the second ever for a player, coming eight days after the Toronto Maple Leafs similarly honored the No. 6 of Ace Bailey, whose career was cut short by injury.

(More than three decades later Bailey would ask his former team to allow Ron Ellis to wear No. 6, which Ellis did from 1968 until his retirement in 1981.)

The Senators would spoil Lionel Hitchman Night on Feb. 22, 1934, scoring twice in overtime -- you're better not knowing early rules -- for a 3-1 victory.

But the Bruins stalwart didn't leave the building empty-handed, carrying two checks of $500 each, one from team management, the other from fans, and a variety of gifts. The defenseman's stick and jersey were presented to his parents, who had travelled from Ottawa for the occasion.

Hitchman came to the Bruins from the Senators, the Toronto native having moved with his family to Ottawa, where he made his NHL debut late in the 1922-23 season.

He had arrived in the League from a curious background, a constable in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police who was scouted while playing senior and civil-service hockey.

Relegated to spot duty behind defense regulars King Clancy and George Boucher in 1924-25, Hitchman asked the Senators that he be loaned temporarily to Boston to increase his ice time.

The transfer was made, though Bruins owner Charles Adams didn't much like the idea of accepting a handout.

"I cannot accept charity from the Ottawa club or any other club for that matter, and furthermore I do not intend to," Adams told the Montreal Gazette, quoted in Eric Zweig's 2015 biography of Bruins manager, coach and hockey pioneer Art Ross.

"I appreciate [Senators manager Tommy] Gorman's offer but we would a great deal rather lose with our men than win with players borrowed from other clubs. We will stand or fall upon merits of the team of our own that we can put on the ice. … I am ready to buy hockey players or trade them, but I haven't got to where I have any desire to borrow them."

© Brian Babineau/Getty Images

The Senators sold Hitchman to the floundering Bruins the following day and it wasn't long before their new defenseman assumed such a strong role that he was named captain in 1927; Boston had played its first three NHL seasons without one.

Hitchman never would be a marquee star in Boston, where he patrolled the blue line for nine-plus seasons. The spotlight mostly would follow defense partner Eddie Shore, who arrived in 1926-27 and became the Bruins' first legitimate superstar.

And when the beam wasn't shining on Shore, other Bruins were basking in it, among them future captain Aubrey "Dit" Clapper and goaltender Cecil "Tiny" Thompson, each bound for the Hockey Hall of Fame.

But it was Hitchman's rock-solid work in the defensive end that allowed Shore to go on the rush and become a fearsome offensive threat.

"Shore may be the dynamo of the Boston club but Hitchman is the balancing wheel," author C. Michael Hiam quoted a Boston columnist in his 2010 biography of Shore.

Former Bruins center Frank Frederickson compared the two defensemen in a 1968 interview with Stan and Shirley Fischler in the book, "Heroes and History."

"[Shore] was a good skater and puck-carrier but wasn't an exceptional defenseman like his teammate Lionel Hitchman," Frederickson said. "Hitch was better because he could get them coming and going."

Hitchman had been joined in Boston from 1925-28 by former opposition sparring partner Sprague Cleghorn, a large package of bad attitude with whom he had feuded regularly. During the 1924 Stanley Cup Playoffs, Cleghorn, then a physical presence with the Montreal Canadiens, had relieved Senators rookie Hitchman of a few teeth.

"Hitchman learned a lot from Cleghorn but did not adopt some of Sprague's lesser attributes," author Charles L. Coleman wrote in his seminal 1969 three-volume, "The Trail of the Stanley Cup."

Hitchman led the Bruins to their first Stanley Cup Final appearance in 1927, but they lost to the Senators. He took them to first place in the American Division the following season and in 1928-29. He had one goal in 38 games but anchored a defense that allowed 52 goals in 44 games.

In 1929 the Bruins won the Stanley Cup for the first time, setting an American Division record for wins (26) and goals scored (89).

Tiny Thompson out-dueled Canadiens goalie George Hainsworth in a three-game first-round sweep, the Bruins advancing on the back of Hitchman, bloodied and bruised. A sweep of the New York Rangers in the best-of-three Stanley Cup Final sent all of Boston into hysterics.

At the Bruins' victory banquet, manager Art Ross singled out his captain for praise, calling Hitchman "a cornerstone of the franchise."

He would finish second in balloting the following season for the Hart Trophy, voted to the player deemed most valuable to his team, and soldiered on as one of the NHL's most unsung greats, of his or any other generation.

In time, Hitchman would get a little of his due.

In late January 1934, the end of his playing career at hand, the Bruins named him manager of the Bruin Cubs, their Can-American league farm team. He was charged with developing young talent for the NHL club.

His industriousness and resilience were noted:

"At the start of the present season Hitchman had a bad charley horse and was bothered by a head cold," Arthur Siegel wrote in the Boston Herald's Feb. 1, 1934 edition. "The Bruins had been trounced in Toronto and the defense situation was acute. Yet Hitch went out and played without complaint, refusing to stay in bed as he should have done."

At retirement, Hitchman's statistics appeared underwhelming:

His first full season in Boston saw him with a personal NHL-best 11 points in 36 games. He wasn't noted for his physicality; his career-high 87 penalty minutes in 1927-28 were 10th in the League that season. He never played in an All-Star Game.

But Hitchman was a huge presence on those early Bruins teams; a solid, dependable, quiet leader who never sought the spotlight and excelled in the shadows.

He died in Glens Falls, N.Y., in 1969 at age 67.

Now, 82 years to the day since his final game, the defenseman's No. 3 banner hangs above the TD Garden ice in Boston.

It is a black-and-gold tribute to one of the Bruins' early legends whose name would not for a moment look out of place in the Hockey Hall of Fame, celebrated alongside his contemporaries on whose backs the NHL was built.