Editor's note: The Quebec International Pee-Wee Hockey Tournament has been the premier youth hockey event in Canada since 1960, a steppingstone for many future NHL players, including Wayne Gretzky and Connor Bedard. NHL.com senior director of editorial Shawn P. Roarke went to Quebec earlier this month to check out the tournament and all that goes with it.

In the third of a four-part series, Roarke highlights Manon Rheaume’s visit to the tournament and the growth of girls hockey. (Part 1 | Part 2)

QUEBEC CITY -- Nobody is more qualified than Manon Rheaume to explain the importance of having a girls division at the prestigious Quebec International Pee-Wee Tournament.

Rheaume, the only woman to play an NHL game and one of Canada’s most decorated women’s hockey players, was the first girl to play in this tournament, the goalie for her Quebec-based boys team in 1981.

She was the first woman to coach an all-girls team in the boys division here, and she was the first to coach in a Quebec final between two all-girls team in the boys division.

She returned to the tournament as a VIP during its first weekend this time around and dropped the puck for the featured girls game on Feb. 11. There, she saw the impact of her groundbreaking appearance from 40 years earlier.

“To go back this year, to drop the puck for that girls division, it's absolutely amazing,” Rheaume said.

Instead of being a lone goalie lost in a sea of boys, Rheaume had 30-plus girls facing her from opposing blue lines, each an elite hockey player in her own right, looking back and smiling as Rheaume basked in a resounding ovation from an appreciative crowd at Videotron Centre, the primary rink for the tournament and the state-of-the art home of the Quebec Remparts of the Quebec Maritimes Junior Hockey League.

The Quebec tournament introduced a girls division last season, but for many of them on hand, such opportunities have become commonplace.

For current players, the struggles of previous generations are but a distant memory. They often do all the same things the boys do and that applies to the biggest pee-wee tournament in the world. The 12 teams in the Feminin Division are treated the same way as their peers from the boys BB, AA, Elite-AA and AAA divisions in the 120-team tournament.

It’s different for those who lived through the limited opportunities afforded girls and those who had to open -- if not bust down -- closed doors, like the 52-year-old Rheaume and Brooke Ammerman Reimer, the 33-year-old coach of the tournament champion team, the Atlantic Girls Select.

“It's tremendous how many girls are playing and how many options there are now,” Ammerman Reimer said. “We're seeing a huge boom. I know if I was a 9-, 10-, 11-year-old girl like them, I would love this opportunity.”

Ammerman Reimer had more limited opportunities growing up in New Jersey, where the Atlantic Select team is based. She and her younger sister, Brittany, played on boys teams as kids in the Garden State before each landed at the University of Wisconsin and with the United States national team program.

At Wisconsin, Ammerman Reimer had 215 points and won two national championships. She was member of the USA U-18 team and the U-22 team. She was invited to try out for the Olympic team in 2010 and 2014. She also scored the first goal in the history of the New York Riveters in the defunct National Women’s Hockey League.

“We had a lot of, I don’t want to call them dark days, but days where you're training by ourselves and people don't really know that girls can play ice hockey and you know, it's kind of an in-between phase,” she said. “For these young girls, you kind of hope they grow up and they never have to think about that.”

Ammerman Reimer said she thought about all those trials and tribulations throughout the championship game earlier this month.

The lower bowl of Videotron Centre was packed, the crowd was knowledgeable and involved, providing a pulsating backdrop as the Atlantic Selects chased their championship dream against the Laval-Montreal Amazons.

The game was tied 0-0 after the first period, but Lauren Letts scored four straight goals around the game-opening and closing goals by Madeline Staffieri in a 6-0 win. Letts, who had 15 points (eight goals, seven assists) in five games, was the first girl to lead the Quebec tournament in scoring.

“I wanted them to be proud, to really celebrate the victory because I mean, at least I know as an adult, how hard it is to win something like that,” Ammerman Reimer said.

Such opportunities are so important for this generation of girls, says Rheaume, who was the talk of the hockey world when she went to training camp with the Tampa Bay Lightning and played a preseason game in 1992.

Rheaume was the first woman to appear in a professional regular-season game when she played with the Atlanta Knights of the International Hockey League in 1992.

But opportunities were severely limited then, and Rheaume and some of her cohorts on each side of the border were blazing new trails and pushing the envelope when it came to the women’s game, first raising the ceiling and then busting right through it.

Now, there is a unified professional league for women, the Professional Women’s Hockey League, which is in its inaugural season with six teams across North America. The league has been playing to capacity crowds and rave reviews. The national teams in Canada and the United States are fully funded and allow elite players to train full-time. Other countries are catching up when the game is played internationally like at the World Championship and Olympics, tournaments in which Rheaume once represented Canada when participation was a part-time endeavor.

What’s happening now on the women’s side, starting with youth hockey, a seismic shift, she says.

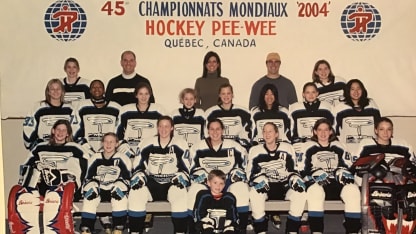

Rheaume remembers taking a select girls team to the Quebec tournament as a coach. The roster was loaded. Kendall Coyne Schofield played on that team, as did Megan Bozek and Blake Bolden and Jordan Slavin, sister of Carolina Hurricanes defenseman Jaccob Slavin. Each went on to play for her country’s national team.

Bolden is a scout for the Los Angeles Kings. Coyne Schofield works for in the Chicago Blackhawks’ front office.

“Those girls didn't have that dream to play professional hockey, you know?” Rheaume said of the elite players she coached. “I have two boys that their entire life, that's what they wanted to do in hockey -- play professionally. But now finally those young girls can have that dream.

“To play in this tournament for these new girls is great because it's an experience of a lifetime. Blake Bolden and I talk about it all the time. She said, ‘Listen, I don't remember one game we played. I remember all the other stuff we did. The billet family, going sledding, playing pond hockey when we didn't have games, exchanging pins, all that stuff.’ Those are the moments that she remembered the most from the tournament, and me too.”

It’s progress that is not only important to the women who came first, but to the girl dads who have made their careers in hockey.

Eric Brewer played 1,009 regular-season games as a defenseman in the NHL from 1988-2015. But there he was as an assistant coach for the North Shore Winter Club, a British Columbia-based team for which his daughter Hadley played.

He was thrilled to have the opportunity to share this experience with Hadley and her friends.

“It’s incredibly important to have an even playing field,” he said, standing outside the dressing room after his team dropped a 3-2 shootout loss to a team from Switzerland. “It enhances their sporting life and their ability to translate into adults, just the same as the boys They're super keen and super competitive. And it's up to us, in this day and age, to provide those opportunities.”

Vincent Lecavalier, who played here as a 12-year-old in 1994, was back at the tournament as a coach this season, coaching the Elite-AA Florida Alliance on which his son Gabriel played. Lecavalier played 1,212 regular-season games in the NHL and won a Stanley Cup with the Lightning in 2004.

He knows this tournament was pivotal in his development as a hockey player and he knows it will be important in the development of his son, especially after the Alliance made it to the championship game before losing.

Now, young girls will have the same opportunity to begin chasing their hockey dreams here on the biggest pee-wee stage in the world and kickstart their development, he said.

“Girls hockey has grown, and you can see in the northeast [U.S.] and even in Canada, the level of play is pretty incredible,” Lecavalier said. “They had to do [add a girls bracket]. I'm happy for them and for the growth of it. It’s just going to get bigger and bigger, bigger and bigger.”